There’s no doubt in my mind that the first music I heard from New Orleans was by Fats Domino, and that he was in my head for well over a decade before the city’s music became a passion of mine. That didn’t take place until I saw Professor Longhair performing in Central Park in 1973, but I would have heard Fats as early as the late fifties, and there the seed was planted. His hit tunes “Blueberry Hill,” “Ain’t That a Shame,” and “Walkin’ to New Orleans,” were part of the aural wallpaper of my youth, and the intriguingly named Antoine Dominique Domino was no stranger to television either. (Since his recent death, I’ve been surprised by the number of people who’ve told me they thought Domino was a nickname that went along with Fats.)

Hearing Professor Longhair’s bare-knuckled synthesis of blues, rhumba, mambo, habanera, and boogie-woogie ignited what felt like a new musical awakening for me, but the truth was that through Fats, I’d been enjoying variations on this musical gumbo since my grammar school days. Much like Louis Armstrong a generation earlier, Domino was the most visible exponent of a musical culture that ran deep and flowed everywhere. And while I responded more directly to the raw blues feeling in ‘Fess and Earl King and Smiley Lewis than to Fats’s more polished and light-hearted effusions, his hits were a constant delight and his hard-driving shuffles “Please Don’t Leave Me,” “Blue Monday,” and “The Fat Man,” became staples of r&b radio shows I hosted 35-40 years ago.

Fats Domino died on October 24 at 89. The amazing run of hit records he enjoyed in the 1950s and ’60s defined a new era in music, and he helped bring into the mainstream the relatively obscure lineage of piano-driven blues and second line parade rhythms of his hometown. In this respect, Domino deserves credit not only as a musical populist, but as a major player in the preservation of a unique musical culture that fuels the city’s tourist industry and the ritualistic appeal of its music festivals. And while his death made headlines globally, it was major news at home, where WWL-TV led its newscast on October 25 with this 13-minute feature, and news anchor Eric Paulsen, who was a friend of the pianist’s, hosted this conversation with trumpeter James Andrews about the city’s second line parade in Fats’s memory. (You’ll note in the right-hand column of this YouTube file numerous features on his death and legacy.)

Domino’s hit parade began to subside over fifty years ago, but through decades of touring behind full-throttle shows and a huge catalogue of recordings, he continually broke through to new generations of listeners. On the home front, his accessibility, humble demeanor, and longtime residency in the marginal 9th Ward neighborhood where he was raised only added to his appeal with musicians. (Domino’s 9th Ward home was flooded in the wake of Hurricane Katrina and he was presumed dead before he and his family were rescued from their rooftop by a Coast Guard helicopter.) One of the most prominent of the locals is Jon Batiste, the 29-year-old pianist who’s best known as the music director for The Late Show With Stephen Colbert. Batiste eulogized Fats in The New York Times on October 28 and concluded his op-ed memorial by saying the pianist died “knowing full well that he holds a rare title: founder of both the jazz and the early rock ’n’ roll establishments.”

Batiste devotes most of the column to his personal odyssey as a young New Orleanian gradually coming to appreciate that African Americans were pioneers of rock’n’roll. Domino stands as Exhibit A for what Batiste calls the “beginning,” and no less a figure than Elvis Presley said as much on a few occasions. But it’s not clear why he adds jazz “founder” to the credits, and it made me bristle not only over its historical inaccuracy, but at the thought of how some of Domino’s own sidemen, as well as jazz players in general, and some of the patrons at the Antibes Jazz Festival, would take issue with the specious claim.

(Here’s Fats at the Antibes singing Louis Jordan’s “Ain’t That Just Like A Woman.” The tall, bar-walking tenor legend Lee Allen, who spent many years touring with Domino and later worked with the Stray Cats and Blasters, is the saxophone soloist; Dave Bartholomew, who was Fats’s music director and the co-composer of several of his hits, plays the 45-degree angled trumpet à la Dizzy Gillespie. Domino was in the inaugural group of Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame inductees in 1986; Bartholomew was elected in 1991.)

I’ve had a fervent appreciation for both jazz and blues for close to 50 years, and right from the start I noticed how dismissive jazz people could be toward blues, not the kind Charlie Parker and John Coltrane and Charles Mingus played, but the downhome blues of T-Bone Walker, Muddy Waters, and even B.B. King. The late Albert Murray, who was prominent in Ken Burns’ PBS series Jazz and a mentor to Wynton Marsalis, once chided the King of the Blues for acting as though what he was playing and sweating over was challenging and new. In recent years, this attitude has mellowed such that virtually all musicians express some degree of respect for the blues masters, but I’ve heard more than one jazz player who’s worked a sideman gig in a blues band mock the music’s predictable rhythmic and harmonic patterns.

It’s not hard to see where frustration would arise in musicians who’ve devoted their lives to the rigorous standards of modern jazz only to find themselves playing basic horn charts and routine chord changes for a living. One of the most glaring examples of this dilemma occurred with Domino sideman Nat Perrilliat, a legendary tenor player who had bebop chops, a heroin habit, and rent to pay in a town which has rarely been hospitable to modern jazz. Perrilliat’s New Orleans colleagues included Harold Battiste, Ed Blackwell, and Ellis Marsalis, and he fronted a post-bop big band in NOLA that remained a proverbial “rehearsal” band. But he worked with r&b greats Shirley & Lee, Professor Longhair, Allen Toussaint, and Joe Tex, and toured with Domino’s road band before his premature death at 34 in 1971. In Blue Monday: Fats Domino and the Lost Dawn of Rock’n’Roll, Rick Coleman cites an article by music journalist John Broven in which he quotes Battiste saying, “[Perrilliat] was out there on the road with Fats Domino, which he didn’t deserve, a musician of his caliber. It was like putting John Coltrane in John Lee Hooker’s band! It’s just not fair and that’s what killed him.” For the record, Battiste spent 15 years earning a dependable livelihood as music director for Sonny & Cher.

Musicians weren’t alone in drawing sharp distinctions between jazz and Domino’s driving blues and boogie-woogie. At Juan-les-Pins, France, site of the Antibes Jazz Fest, Fats shared the 1962 bill with the Clara Ward Singers, Jimmy Smith, and Dizzy Gillespie. In Blue Monday, Coleman says, “A few purists heckled as Fats took the stage,” and one complained that the pianist “had a $4800 watch and didn’t know who Thelonious Monk was.” Robert Houston, a reporter for Melody Maker, said that while Domino’s set was “very entertaining and the crowd loved every minute of it…It was not jazz festival material.”

(Here’s footage of two of the fest’s headliners. Fats enters @9:07 and performs “I Want to Walk You Home” and “Josephine,” and returns @23:40 with “Ain’t That a Shame” and “When the Saints Go Marching In,” complete with Dave Bartholomew leading the horn players in a second line through the crowd. Note that Fats’s guitarist Roy Montrell, who’s pictured here, also plays a tune, “It’s Alright With Me,” with Jimmy Smith.)

Domino was born in 1928, the same year that Louis Armstrong was recording his Hot Five classics “West End Blues” and “A Monday Date,” and Duke Ellington was attracting international attention at the Cotton Club in Harlem. As measured by the timeline enumerated in Jelly Roll Morton’s boast about having invented jazz in 1903, Antoine Domino’s baptism was still a quarter century away from what Batiste calls the music’s “establishment.” Earlier in his otherwise laudable tribute, Batiste says that New Orleans was the birthplace of jazz, that Domino was influenced by it, and that he “bridged” jazz and rock’n’roll. The latter point is questionable, but his “establishment” gambit smacks of cultural overreach, the kind endemic to revisionists. or in this case, disciples for whom one great distinction isn’t enough. One wonders if anyone at The Times noticed or gave it a second thought.

Batiste’s main point. however, is quite valid: that while rock’n’roll is largely black in origin, he had to dig deep in order to make the discovery. Jimi Hendrix was his first touchstone, but it wasn’t until he heard the “percussive piano” of Domino’s “Blueberry Hill” and saw an audience respond to it that he made the connection. In that moment, he says, “I had finally arrived at the beginning: Fats Domino.”

When it comes to citing anyone as a creator of rock’n’roll, I’ll happily go along with Domino, and if one must declare for something as subjective as the first rock’n’roll record, Fats’s 1949 debut, “The Fat Man,” is as solid as any. In Blue Monday, Coleman maintains conventional Elvis-time thinking in saying that it “predated the crossover of rock’n’roll by five years,” and notes that it’s been celebrated as a ground-breaker by John Lennon, Lou Reed, John Fogarty, and Robbie Robertson. I’m continually impressed by the numbers of musicians I’ve spoken with who invoke Fats’s name as a bellwether of their own youthful discovery of African American music, most recently in this conversation with Geoff Muldaur. (As long as I’m on a roll call of rock stars, did you know that Paul McCartney composed “Lady Madonna” with Domino in mind? Along with “Lovely Rita” and “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Besides Me and My Monkey,” it’s one of three Beatles tunes Fats recorded in 1968.)

To underscore just how ambiguous the notion of firsts are in music, consider that “The Fat Man” was adapted from “Junker Blues,” a 1941 recording by Champion Jack Dupree. And “Junker” was the basic prototype for additional piano-driven classics, including “Tipitina” by Professor Longhair and “Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” the 1952 Lloyd Price #1 R&B hit with an uncredited Fats Domino on piano. Now add to this labyrinth one Willie Hall, a pianist whom Dupree credits with creating the tune’s basic arrangement on a ’20s piano blues called, “Drive Em Down.”

Fats didn’t fuss, of course. For him, it was simply r&b, and as true as that was, it may have been a slightly calculated distinction too. As “rock’n’roll” became suspect for the frenzied and occasionally riotous behavior it induced in crowds, Fats had a brand to protect. The music was also controversial for pushing against the limits of segregation and sexual repression. Speaking of the impact of his 5-million seller “Blueberry Hill,” New Orleans legend Irma Thomas, who was about 14 when it hit the airwaves, said, “I didn’t know what the thrill was, but it sure sounded good.” Allen Toussaint noted that Fats’s music had a profound visceral power. Speaking of the simple introduction he plays on his 1951 single, “Goin’ Home,” Toussaint told Rick Coleman, “When Fats plays that, it’s magic. It’s beyond just a general grace note in musical terms. It’s a little bigger than life, just the way Fats is.” The record’s out-of-tune sax solo does little to diminish its power or the immediate influence it had on two more NOLA-recorded classics, Faye Adams’s “Shake a Hand” and Guitar Slim’s “Things That I Used to Do.”

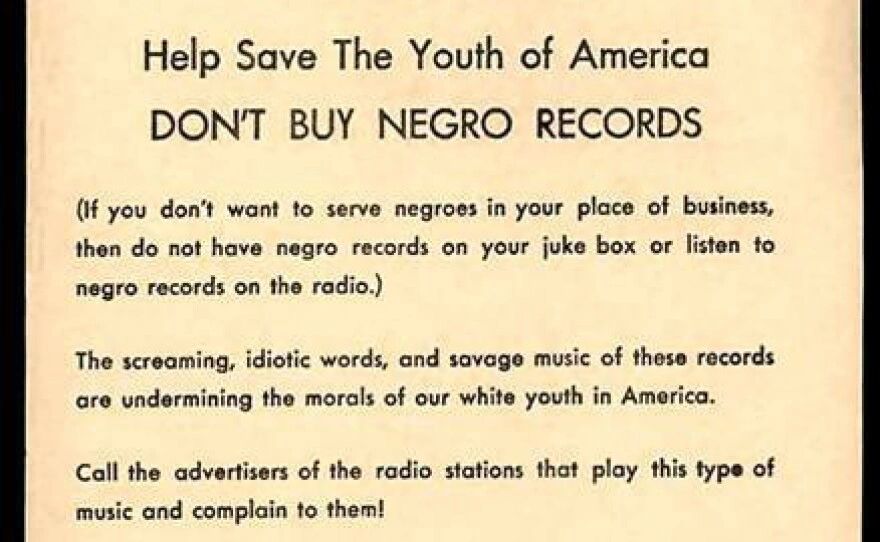

Regardless of how the music was labeled, the fifties witnessed a panicked reaction to the growing popularity of African American music. White supremacist groups warned public establishments to keep records by black artists off their jukeboxes, and violence erupted at venues where the music was blurring rope line demarcations between the races. Elvis and Jerry Lee Lewis may have been daring, but black artists like Domino, Chuck Berry, and Bo Diddley were the ones really laying it on the line. Fats was rarely outspoken on matters of civil rights and he drew occasional criticism from the NAACP for playing segregated venues in his hometown, but his nationwide popularity brought blacks and whites together in ways that made segregation and Jim Crow customs impossible to defend or maintain, and helped spur enormous changes in American society.

At the time, Fats told interviewers that the music then catching on with an ever-expanding youth market was the same as he’d been playing since the early forties in New Orleans. That seems obvious, in retrospect, but in that time and place, music popular with African Americans was still mostly beyond the view of the white mainstream. Domino, of course, helped change all of that with a winning smile, an infectious style, and as bebop legend Howard Johnson noted in Dizzy Gillespie’s autobiography To Be or Not to Bop, the restoration of a “beat that…was lost for a few years until Fats Domino brought it back.”

(Here’s a ringer with Fats and The Byrds on a Washington, D.C. TV show in 1973 playing “I’m in Love Again,” “I’m Ready,” and a capstone of “Walkin’ to New Orleans,” complete with Fats explaining the song’s changes to Roger McGuinn and guitar legend Clarence White.)

Any number of Domino tunes will illustrate what Jon Batiste calls the “joyous communal power” of his music. With his 1950 single, “Every Night About This Time,” Fats introduced an original that became both a personal prototype and a blues standard. “Every Night” was Fats’s second r&b hit, and the first to use the piano triplets that became his signature. Little Richard’s 1957 cover featured a biting guitar solo by Buster Douglas, and that may have inspired later covers by Magic Sam and Luther Allison. “Every Night” is one of the very few examples of a NOLA tune entering the repertoires of Chicago bluesmen.

In 2010, New Orleans newsman Eric Paulsen arranged a downhome reunion (Antoine’s people might call it a “rapprochement”) between 82-year-old Fats and 90-year-old Dave Bartholomew. The trumpeter was there from the outset, leading the backing band at J&M Studio on North Rampart Street when Antoine Domino began “carrying on” as The Fat Man, and at 96, he survives the man who made him famous far beyond the Big Easy.

Fats’s appearance at Antibes may have upset a few purists, but the discovery of his 1962 performance on film a few years ago inspired the 2016 PBS documentary, Fats Domino and the Birth of Rock’n’Roll. This clip from Antibes of “Don’t Want You No More” features Herb Hardesty on tenor, Dave Bartholomew rising from his rusty dusty to solo on trumpet, and guitarist Roy Montrell. In 1954, eight years before this concert, Fats shared the bill with The Clovers on a national tour. Recalling a night in Richmond, California, Harold Winley of the Clovers exclaimed, “Man! Just to see the frenzy! Fats did that ‘Woo-woo-woo.’ Papoose Nelson was answering on guitar. Tenoo was back there [on drums]. That shit was gone, man!”

Here’s some lagniappe for those of you who’ve made it this far. Scroll to 32:11 for Fats “playing a little blues on the piano.” He digs right into “After Hours” and Herb Hardesty blows “Blues in the Night” before Fats settles into “Since I Lost My Baby.” And @10:10, he serves up a killer version of “The Fat Man.” Let’s face it, like the greatest of the greats, Fats always left us wanting a little more, and what a delight it is just now to discover these nicely arranged gems.