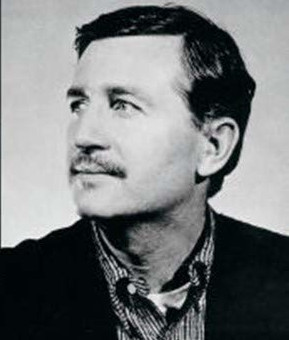

Mose Allison, who died on November 15, four days after his 89th birthday, told NPR in 1986 that his songs could be grouped in three categories, “Slapstick, social comment, and personal crisis,” then added, “Sometimes all three of those elements wind up in a tune.” I hear them all in “I Don’t Worry About a Thing,” a fatalistic song resting on the belief that, “Nothing’s gonna work out fine.” Here it’s performed by Mose in 1975 for the PBS series, Soundstage.

I was new to jazz when I began listening to Mose Allison, and first heard him at Clark University in Worcester in 1969 or ’70. I was around 16, not yet driving, and enough of a greenhorn to lavish praise on him when he sidled up next to me in the men’s room after the show. To my exclamation, “Wow, that was great!” he replied, “And you would know?” I blushed at what felt like a brusque bit of rudeness, but given the countless times since then that I’ve heard musicians say that what often strikes audiences as a masterful performance is ho-hum to them, I credit Mose with implanting that perspective in me early on. On the few occasions when I introduced him at nightclubs and festivals, I knew better than to say anything that smacked of hype.

Allison’s early renown came in the mid-fifties for his work as a percussive, hard-swinging pianist in bands led by Stan Getz, Bob Brookmeyer, Gerry Mulligan, and the two-tenor combo led by Al Cohn and Zoot Sims. With the latter, he played long engagements at the Half Note in New York, and a couple of summers at the Atlantic House in Provincetown. His jazz chops served him well as a singer-songwriter who elaborated on tunes with concise solos of a chorus or two; in a JazzWax interview in 2010, he credited the singer-pianists Charles Brown, Ray Charles, and Percy Mayfield as primary influences, and named jazz greats Al Haig and John Lewis as model accompanists.

But it was the folksy, homespun humor and sardonic wit of the Tippo, Mississippi, native’s songs that made him an influential figure on rock and blues musicians emerging in the sixties. Pete Townsend was an art student in 1963 when an American classmate played him a stack of blues albums, three of which were by Mose. A decade later, in his liner note essay for Mose Allison’s Greatest Hits, Townsend recalled thinking Mose was black, and when his friend showed him the album jacket, he says he “screamed, ‘He’s white!'” Townsend said that “from that day, as I walked down city streets, I imagined myself to be Mose…A real, cool, relaxed, genuine, funky, hipped out, white hero.”

Mose sang in what Townsend called a “heavenly voice. So cool, so decisively hip…the epitome of restrained power…His voice was so right that I felt it was the voice of the gentle giant…with the strength to change the world, but the humility and the character to stand alone, live his own life, and await his natural time.” Townsend adapted The Who’s “My Generation” from Allison’s “Young Man Blues.”

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yK2-nAR0Aks

Mose’s laid back delivery and deep command of tension and release reminds me of Muddy Waters, who described himself as a “delay singer.” Though highly renowned for his own songwriting, he didn’t shy away from building up a repertoire that included tunes by Muddy, Willie Dixon, Nat King Cole, Charles Brown, Buddy Johnson, Big Joe Williams, Percy Mayfield, and several of Duke Ellington’s great standards. The songs he covered often impressed me as idiomatic counterparts of his own material, and he’s occasionally mistaken as the composer of a few of them, including Brown’s “Fool’s Paradise” (co-written by Johnny Fuller and Bob Geddins), and Dixon’s “Seventh Son,” and “I Love the Life I Live.” Perhaps in an effort to counter such misunderstandings, Mose invariably named the writers (composers and lyricists) of the tunes he sang in person.

Here’s Mose on the Soundstage broadcast performing “Your Mind Is On Vacation,” a seminal put-down song that I hear paving the way for tunes like “Positively 4th Street,” “Like a Rolling Stone,” and “Saint Dominick’s Preview.” I don’t think Bob Dylan mentioned Mose in Chronicles, Volume One, but Van Morrison’s sung his praises and his tunes, and in 1996 he joined Georgie Fame, who always proclaimed Mose more important than Dylan, in a tribute album to Mose, Tell Me Something. It was produced by Ben Sidran, the singer-pianist who championed Mose “an enigma in the tradition of great jazz enigmas….” In his liner note essay for Allison’s 1987 album, Ever Since the World Ended, Sidran wrote, “His lyrics perpetuate the enigmatic nature of his persona. They appear to be straight-forward autobiography, but he categorically denies this. Rather, he would have us treat these musical messages as a kind of delayed fiction…His songs paint such an accurate picture of life…that one can almost taste the dust of the highways he’s traveled. Yet beneath this fine powder, the casual surface of humor and offhand observation, there is, quite often, a very deep chasm created by the revelation of some awful truth.”

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pCpekvOkwNM

In 1962, Mose recorded “I Ain’t Got Nothin’ But the Blues,” and added a closing verse to the Ellington tune that concisely reflected both a skeptical view of post-WWII suburbia and the elegiac feeling that gripped the jazz world after Lester Young’s death in 1959. “Ain’t got no house in Westchester/Don’t have no Criss Craft to cruise/Ain’t got no Basie with Lester/I ain’t got nothin’ but the blues.” Alas, the same is now true for Mose Allison.