Jazz Great from the Bay State

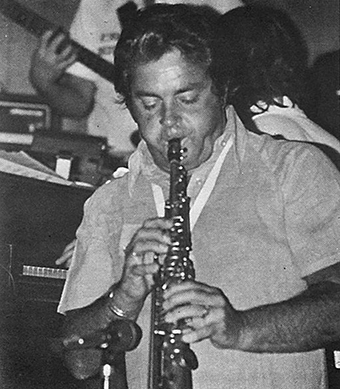

Dick Johnson’s 90th birthday anniversary was December 1. The Brockton, Mass native, who died in 2010 at age 84, came to prominence in the fifties, one of the legion of Charlie Parker-influenced alto saxophonists then populating the jazz world. An even better known member of that tribe, Springfield’s Phil Woods, died this fall at age 83. Like Phil, Johnson was a conservatory trained clarinetist who studied at New England Conservatory in the late forties; Woods earned his degree at Juilliard in 1952. Unlike Phil, for whom New York became a beacon when he was in his mid-teens, Johnson remained in Greater Boston, living around Brockton, teaching at Berklee, and making a livelihood in music. (Johnson and Woods are two of the four Bay State alto greats who’ve passed in recent years; Boston-born Charlie Mariano died in 2009, and Medford native Hal McKusick in 2012.)

I wrote about Johnson in this eulogy for trumpeter Lou Colombo in 2012. For me, Johnson, Colombo, and Dave McKenna will always be yoked as New England jazz greats who gave real distinction to the region’s music scene for over a half century. They were also among that rare breed of bebop-oriented players who became stylists for all seasons and occasions. Johnson and his Brockton compatriot Colombo co-led a combo for a dozen years beginning in 1960, and Johnson joined McKenna for a few years at the Columns in West Dennis on Cape Cod in the early seventies. That’s where I first saw them, and the experience was formative in shaping my understanding of the jazz life and my appreciation for the tunes that form the core of the American songbook.

In a 1975 cover story for Jazz New England, Johnson told Everett Skehan that Colombo, who was as garrulous as Johnson was cool, was a perfect partner for a group that needed to play both jazz standards and contemporary pop seven nights a week. Of McKenna, he said, “Dave is a perennial. He can go any bag. He’ll gas the most modern mind, and the most moldy fig. Dave McKenna’s an out-and-out genius.” In a 1983 interview for The Jazz New England Journal, Johnson recalled that when he first heard the 18-year-old McKenna at a jam session in Brockton in 1948, he became “my favorite [pianist] after one introduction.”

Johnson played in the Navy band during World War II, and upon discharge in 1946 heard Parker and Dizzy Gillespie on record for the first time. “We really thought [the buzz about Bird] was kind of strange until we got the records. Then we knew it was somethin’ else.” After graduating from NEC, he joined Charlie Spivak in 1952, then toured with Buddy Morrow for several years; in the latter outfit he played in the orchestra and was featured in a small group from within the band’s ranks, much like the small groups led by two of his favorite big band clarinetists, Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw.

He led two quartet sessions for prestigious jazz labels in the mid-fifties. A 1956 date for Emarcy, Music for Swinging Moderns, was an all-standards album recorded in Chicago with colleagues from Morrow’s band. The following year, he made Most Likely for Riverside, which featured McKenna and the redoubtable rhythm section of Wilbur Ware, who was then the bassist with Thelonious Monk’s Quartet with John Coltrane, and drummer Philly Joe Jones of the Miles Davis Quintet. Both sessions feature Johnson exclusively on alto, and while they’re both excellent, neither album, nor his appearance at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1957, pushed him to the front ranks. It would be 16 years before he recorded again on a McKenna date, and 23 before he made another album as a leader. His 1980’s releases on Concord Jazz, Spider’s Blues and Dick Johnson Plays, and a showcase with McKenna, Piano Mover, are modern mainstream outings that feature Johnson on the full array of woodwinds and flutes that he was long a master. All three are highly recommended and worth the effort of seeking out; the two albums pictured on this page are available here from Amazon.

In the Jazz New England feature, Johnson said that Goodman, with whom he’d played, was an early favorite along with Louis Armstrong, but he favored Shaw “because he had a much more modern approach to music. I can’t over-stress the Artie Shaw influence. To me this guy is like a missing link in the jazz world. There was Armstrong, and then they figured there was no real biggie until Charlie Parker. [Actually, most jazz historians give great priority to the innovative approach of Lester Young in the late thirties.] I think Shaw was so perfect that they took him for granted…He was playing bebop lines before anybody knew what was happening.”

At the time of the Jazz New England feature, Johnson had never played with nor met Shaw, who for all intents and purposes had retired from music around 1954. But on December 18, 1980, Shaw wrote to Johnson’s manager Bill Curtis to say, “You wanted to hear what I think of Dick Johnson’s clarinet playing. Okay, as of this time, he’s the best I’ve ever heard. Bar nobody. And you can quote me on that, anywhere, anytime!”

Three years later, when Shaw answered many years of urgent calls from booking agent Willard Alexander to front a new touring orchestra, it was Johnson who got the call to play the clarinet solos. By 1986, when Shaw tired of conducting duties, Johnson took over as bandleader. Here’s Shaw conducting a performance of “Stardust” that features both Johnson and Lou Colombo playing lead trumpet.

For Johnson, it was all a dream come true, and he said as much to the audience gathered for the annual jazz educators convention in Long Beach in January 2005. There he accepted the NEA Jazz Masters Award for Shaw, who’d died one month earlier. He began by talking about how iconic “Artie and Benny” were to young reed players around 1940. “If I ever knew that I was going to be leading his band at that time,” he said, “I wouldn’t be here today. I’d have been too scared.” I’ll never forget the sound of Johnson’s telltale Brockton accent filling the auditorium in Long Beach as he talked about Shaw and what an honor it was to be associated with his idol. I never knew Johnson personally, but he was my idol that night.

I saw Dick Johnson in many different settings between 1972 and 2008. Among the most memorable were the last two. On a cold winter’s night in 2003, Johnson was playing with Colombo and a bassist in the tiny parlor of an inn in Chatham on Cape Cod. He’d played alto on the several selections that we arrived in time to hear, and at the end of the set he asked the enthusiastic crowd of ten patrons what we wanted to hear? I spoke up and asked for something on clarinet, and he obliged with a thrilling performance of “After You’ve Gone,” one that began at medium tempo and picked up speed with each successive chorus.

The last time I saw him in concert was with Jack Senier’s All-Stars at the 1794 Meetinghouse in New Salem, a town bordering the Quabbin Reservoir in Central Massachusetts. He played alto for most of that gig too, but what I’ll long remember is a performance of “Memories of You” that he played in the middle of the second set with what appeared to be a cold clarinet. It didn’t matter. Artie Shaw’s favorite was still at his best at age 81.

Somehow it seems appropriate that the last time I saw Dick was when he spoke at Dave McKenna’s memorial service in Woonsocket, R.I. on December 7, 2008. McKenna and Johnson came of age during the bebop era, and the music was always in their hearts and often in their set lists. But for working musicians, playing modern jazz would hardly sustain a livelihood, so they specialized in standards and swing, music for dancing and conversation. Theirs was a social music, and they played it with a sense of style and conviction that I fear is passing right along with them.

Click here to see Dick with vibraphonist Ed Saindon’s Quintet in a 1997 concert in Worcester that also features trumpeter Herb Pomeroy. It’s well worth the time involved in downloading the concert (Show 84 on the Jazz History Database) just to see Johnson’s unaccompanied chorus on “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” but the whole set is great.