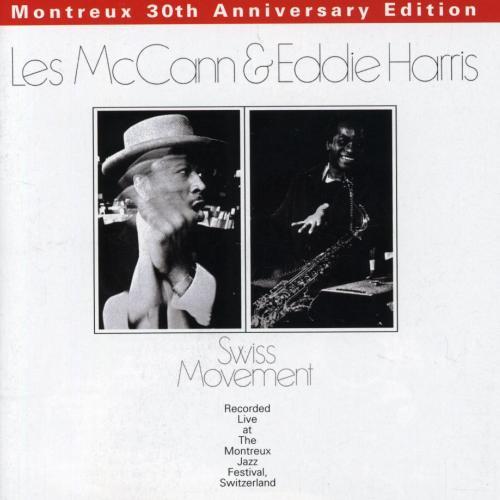

Swiss Movement Live at Montreux

I remember just where I was when I first heard Swiss Movement, the concert album by Les McCann and Eddie Harris recorded at the 1969 Montreux Jazz Festival. I was with a group of friends, mostly high school classmates, and we were skipping school. One of our number’s extended family lived in a spacious apartment in downtown Worcester and he had the run of the place for a week, so we were there to pursue the kinds of cultural alternatives that helped us rationalize truancy. 50 Franklin Street, which retained the elegance of its original incarnation as the Bancroft Hotel, was around the corner from Arnold’s Music, and once Arnold’s opened on Tuesday morning (arrival day for new releases), a small party of us headed over to buy a handful of albums including Swiss Movement. I don’t remember if it was the first album we listened to upon our return, but once it hit the turntable, we didn’t listen to much else for the rest of the week. Indeed, we played it so often that we had to buy another copy before week’s end, though whether that was due to wear and tear or someone stepping on it is a long forgotten detail.

Swiss Movement was the result of one of those spontaneously conceived meetings between players that factor significantly in the annals of jazz. In this case, it involved Les McCann’s trio with bassist Leroy Vinegar and drummer Donald Dean, tenor saxophonist Eddie Harris, and trumpeter Benny Bailey. Neither Harris nor Bailey had ever played with McCann, but the saxophonist and pianist were among the most successful jazz artists under contract to Atlantic, and Harris was on the Montreux bill with his own quartet. Combining super chops and a uniquely vocalized tone, he’d already scored jazz’s first gold record with his 1961 album, Exodus to Jazz, and his 1968 release, The Electrifying Eddie Harris, was on the charts. When producer Joel Dorn proposed that he play a secondary set with McCann, he thought, ‘Why not? After all, it meant I could get some extra money.”

Benny Bailey had been an expatriate for the better part of 15 years by 1969, and remained so until his death in the Netherlands in 2005. He’d first played Europe in 1948 as a member of Dizzy Gillespie’s orchestra, then jumped off the Lionel Hampton Orchestra when the band toured Europe in 1953. (That was Hamp’s legendary band with Clifford Brown, Art Farmer, Gigi Gryce, and Alan Dawson.) By the late sixties, he was playing with the Swiss Radio Orchestra and living in nearby Lausanne. Sitting-in with locals and touring icons was second nature to him, but the trumpeter whom Quincy Jones praised as “a consummate player and stylist…and, above all, thrillingly himself,” was reluctant to join the ad hoc proceedings at Montreux. “Les’s [soul jazz] bag was one which Eddie had no problem with, but it really wasn’t my kind of music. Still, when they asked me if I’d play a set with them…I thought, ‘Why not’?”

By jazz standards, Swiss Movement was a rare, “certified Gold,” hit. Upon its release in October 1969, it rose to the top of the Jazz charts, reached No. 2 on the R&B chart, and No. 29 on the Album chart. Its success was driven by the irresistible groove and sardonic message of the album’s opener, “Compared to What.” Composed by Gene McDaniels, McCann introduced it into his nightclub sets in 1963 and recorded it on his 1966 album, Les McCann Plays the Hits (where it was as yet more filler than hit). It gained new traction on Roberta Flack’s 1969 debut, First Take, where it was played as a boogaloo driven by Ron Carter’s bass. McCann, who’d discovered the singer-pianist working in a Washington, D.C. nightclub and introduced her to Atlantic, was an ardent fan. “Her voice touched, tapped, trapped, and kicked every emotion I’ve ever known. I laughed, cried, and screamed for more…she alone had the voice.”

McCann has a voice too, of course, and its raspy texture, combined with his gospel-tinged piano, Bailey’s sassy plunger mute solo, and the soulful cry of Harris’s tenor, made the Montreux stage feel like church, only in an anti-church kind of way.

Church on Sunday, sleep and nod

Tryin’ to duck the wrath of God

Preacher’s fillin’ us with fright

They all tryin’ to teach us what they think is right

They really got to be some kind of nut (I can’t use it!)

Tryin’ to make it real — compared to what?

For most of us, Swiss Movement was a thrilling aural experience. But as Europeans are wont to do, a production crew filmed the performance, and when I came upon it recently on YouTube it took me right back 46 years to the week we spent obsessively listening to the album. For the 30th anniversary edition of Swiss Movement, Harris explained why the players are so close to one another. “I told Les just to play his usual stuff…and I would look over his shoulder to check the chords…We had one microphone for Benny and me, and there was one television camera set right in front of us…but I couldn’t stand out in front [of the stage] because I had to watch Les and play at the same time…It turned out to be a magical concert.”

McCann ascribed the magic to two additional details. He’d lost over 120 pounds in the eighteen months preceding Montreux, and he’d “smoked some hash…for the first time in my life…When I got on the bandstand, there I was, the new slimmed-down McCann, trying to look cool, and I didn’t know where the hell I was. I was totally disoriented. The other guys said, ‘OK, play man!’ Somehow I got myself together and everything just took off.”

Swiss Movement merited a full-page celebration in Ahmet Ertegun’s self-congratulatory coffee table volume, What’d I Say: The Atlantic Story. Neither his brother Nesuhi Ertegun, who led Atlantic’s jazz division, nor Joel Dorn attended Montreux that year. Dorn recalled, “Nesuhi and I produced Swiss Movement by remote control…The tapes came back and we couldn’t believe it…With this record, it really happened by itself, it was a gift from God. The album and the single, “Compared to What,” each sold in excess of a million, which for jazz music was very rare in those days. Gene McDaniels wrote the single’s lyrics, which were not casual, but were really riding the crest of the whole civil rights movement…The whole thing struck at middle class values– black or white at that point, it didn’t make a lot of difference. It really hit a chord.”

That’s a chord that spelled success not only for the players and their label, but for the festival too. Montreux was only in its third year by 1969, but Swiss Movement helped make it the most iconic of European festivals, and it was probably the last time the Atlantic brass missed it. For McCann, whose 80th birthday was September 23, it was a milestone. “Swiss Movement was certainly a major landmark in my career. And it was a one-off phenomenon, something that can never be repeated.”