The Creator of

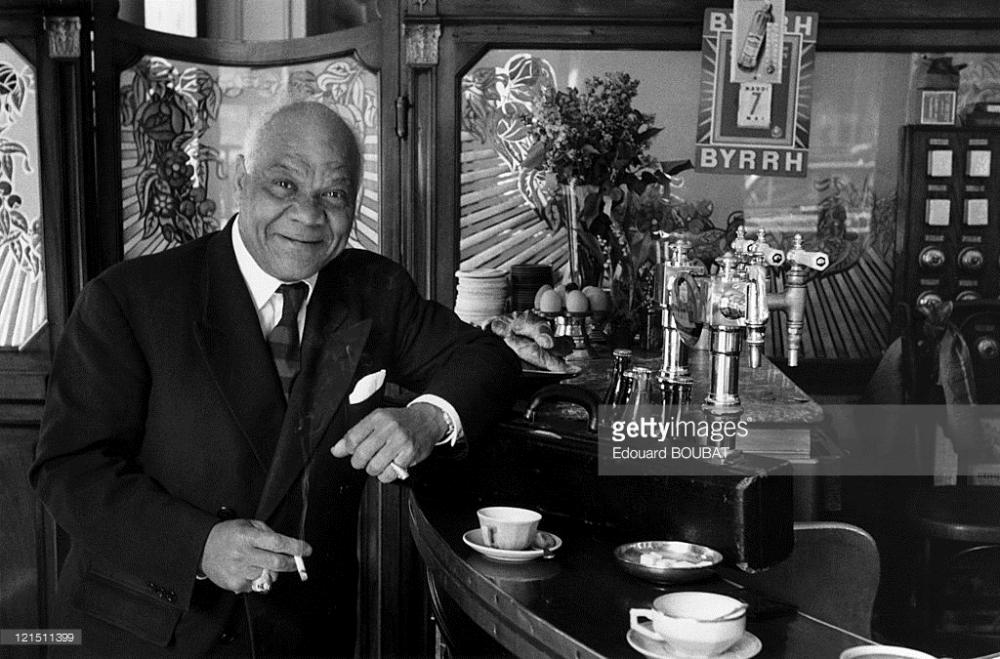

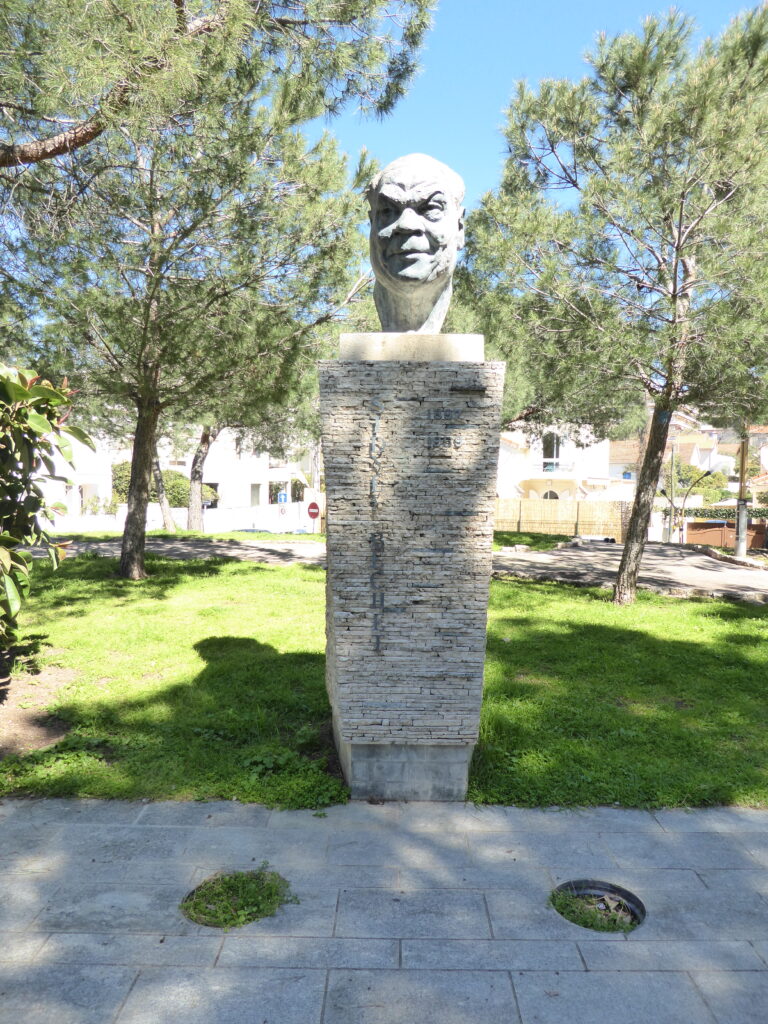

We’ve long recognized the leading role jazz played in breaking down racial barriers in the U.S., but credit Sidney Bechet for effecting a rapprochement between the English poet Philip Larkin and the people of France. Bechet made his home in Paris and Juan Les Pins for the last decade of his life, and there became what Larkin called a “deified” figure who “ruled traditional French jazz…by his own excellent example.” In his memorial to Bechet, “A Real Musicianer,” published in The Guardian on April 8, 1960, Larkin conceded, “For once, one feels the French were right.”

Four years later, Larkin published “For Sidney Bechet” in The Whitsun Wedding. The poem concludes:

“On me your voice falls as they say love should,

Like an enormous yes. My Crescent City

Is where your speech alone is understood,

And greeted as the natural noise of good,

Scattering long-haired grief and scored pity.”

Larkin was hardly the first European to revere Bechet. In 1919, when he was playing in London as a member of Will Marion Cook’s Southern Syncopated Orchestra, Bechet impressed the Swiss conductor Ernest Ansermet, who hailed the New Orleans native for the “perfectly formed blues” he played on clarinet. Ansermet’s review marked one of the earliest occasions in which a jazz performance was seriously covered in print, and after commenting on the unique timbres produced by this ensemble of black instrumentalists, he devoted a paragraph to Bechet:

“There is in the Southern Syncopated Orchestra an extraordinary clarinet virtuoso who is, so it seems, the first of his race to have composed perfectly formed blues on the clarinet. I’ve heard two of them which he had elaborated at great length, then played to his companions so that they could make an accompaniment. Extremely difficult, they are equally admirable for their richness of invention, force of accent, and daring in novelty and the unexpected. Already, they gave the idea of a style and their form was gripping, abrupt, harsh, with a brusque and pitiless ending like that of Bach’s Second Brandenburg Concerto. I wish to set down the name of this artist of genius; as for myself, I shall never forget it, it is Sidney Bechet. What a moving thing it is to meet this [musician] who is very glad one likes what he does, but who can say nothing of his art, save that he follows his ‘own way,’ and then one thinks that this ‘own way’ is perhaps the highway the whole world will swing along tomorrow.”

Ansermet’s prescience stands as one of the benchmarks of jazz criticism, but I’m intrigued by Bechet’s reported reticence to say anything “of his art.” (Click here for an earlier post on Bechet that includes a comment by Mark Miller of Toronto about what is most likely the first serious notice on a jazz musician, written in 1914 about the Clef Club trombonist Frank Withers.) Whether owing to youthful diffidence or a wizened concern about giving away too much, Bechet was generally not a man with “nothing” to say. His interviews and correspondence are quoted throughout John Chilton’s excellent biography, Sidney Bechet: The Wizard of Jazz, and in his last years he set down a fascinating as-told-to autobiography, Treat It Gentle. Bechet’s story of his grandfather Omar is as compelling as the most suspenseful slave narratives and in its imaginativeness is worthy of comparison with Faulkner or Toni Morrison. Rarely has anyone written with such insight about the primacy of music in African American culture.

“The only thing they had that couldn’t be taken from them was their music. Their song, it was coming right up from the fields, settling itself in their feet and working right up…into their spirit, into their fear, into their longing…it was a feeling in them, a memory that came from a long way back. It was like they were trying to work the music back to its beginning and then start it over again and build it to a place where it could…become another music, a new beginning that could begin them over again.”

Perhaps Bechet was wary of Ansermet’s intentions. Their encounter took place four years before he would begin making records in 1923, and he’d already taken note of his fellow New Orleanian Freddie Keppard’s reluctance to record when he was approached in 1916. In Treat It Gentle, Bechet wrote of the Keppard matter: “These people was coming to make records, they was going to turn it into a regular business, and after that it wouldn’t be pleasure music.” Here and elsewhere, Bechet seems less concerned about the potential for commercial exploitation of the music than he is for its corruption as the cultural expression of his people.

Duke Ellington was a great admirer of Bechet, whom he hailed in The World of Duke Ellington as “the greatest of all the originators. Bechet, the symbol of jazz! His things were all soul, all from the inside.” In Music Is My Mistress, Duke wrote, “I shall never forget the first time I heard him play at the Howard Theater in Washington around 1921. I had never heard anything like it. This was a new sound and conception to me.” Four years later, Bechet played with the Ellington orchestra during its summer tour of New England where he engaged in “nightly cutting contests” with the amazingly expressive trumpeter Bubber Miley. Duke recalled, “Often, when Bechet was blowing, he would say, ‘I’m going to call Goola this time!’ Goola was his dog, a big German shepherd…Call was very important in that kind of music. Today, the music has grown up and become quite scholastic, but this was au naturel, close to the primitive, where people send messages, calling somebody, or making facts and emotions known.”

What Duke calls au naturel is most likely what Bechet had in mind as “a question of feeling” when he assessed the work of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, the group credited with making the first jazz records in 1918. “Some of the white musicians had taken our style as best they could. They played things that were really our numbers. But, you understand, it wasn’t our music. It wasn’t us. I don’t care what you say, it’s awful hard for a man who isn’t black to play a melody that’s come deep out of black people. It’s a question of feeling.” Bechet dismissed the ODJB’s recording of “Livery Stable Blues” as a “burlesque of the blues. There wasn’t anything serious in it anymore.”

Bechet would eventually encourage the young Bob Wilber when he took the teenaged “Scarsdale Kid” under his wing in the 1940’s. Wilber recalls his time with Bechet in this interview I conducted with him in 2010, and we’ll hear his new recording of Bechet’s “Blue Horizon” in tonight’s Jazz a la Mode. After settling in France in 1949, Bechet worked extensively with the bands of Claude Luter and Andre Reweliotty, players like Wilber who were dedicated to what Bechet called “playing the music the way it wants to be played.” Here’s rare footage of the master accompanied by Reweliotty’s ensemble in a 1952 performance of “St. Louis Blues.”

Today is both Bechet’s 118th birthday anniversary and the 56th anniversary of his death. Here’s an excerpt of a documentary on Bechet with testimonials from Bob Wilber, Wynton Marsalis, Woody Allen, and Dr. Michael White. Allen marvels over the “feeling, so much feeling in the playing” of Sidney Bechet. We’ll hear Bechet throughout tonight’s Jazz à la Mode.