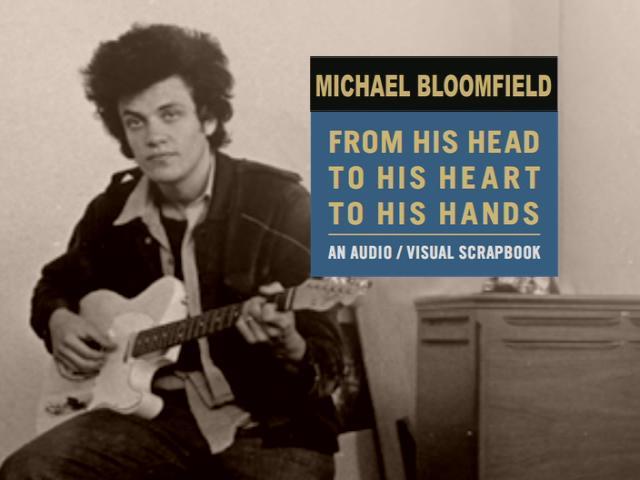

The blues-rock icon Michael Bloomfield is the subject of a new 3-CD retrospective produced and “curated” by Al Kooper for Columbia/Legacy. From His Head to His Heart to His Hands includes a smattering of essentials (but misses numerous others) from the guitarist’s major mid-Sixties associations, Bob Dylan, Paul Butterfield, and The Electric Flag. It also includes the single track he made with Janis Joplin, one cut from his 1969 outing with Muddy Waters and Otis Spann, Fathers & Sons, and two from his voluminous work with Chicago sidekick Nick Gravenites, which includes some of his greatest on record. Gypsy Good Time, from Gravenites’ legendary My Labors, is a prototype of the playing Bloomfield fostered in his young protégé Carlos Santana. Among the set’s rarities are three instrumentals, the Merle Travis-influenced, “Hammond’s Rag;” a band track sans vocal of “Like a Rolling Stone;” and “Susie’s Shuffle,” from a concert by the Flag.

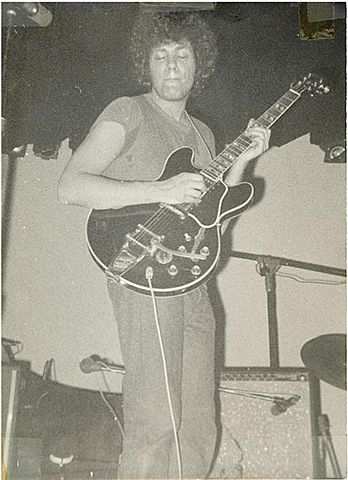

Santana is one of several Bay Area figures who testify to Bloomfield’s amazing musicianship and good-natured personality in the Bob Sarles-directed Sweet Blues, a a “visual scrapbook” that’s included in the boxed-set. Everybody loved Michael, even Country Joe McDonald, whose music, Bloomfield told Rolling Stone, was “an abomination.” Bob Weir and Jorma Kaukonen also sing his praises, though their respective groups, the Grateful Dead and Jefferson Airplane, were routinely trashed by Bloomers, the former for sounding amateurish and lacking “a good beat;” the latter as a “third-rate rock’n’roll band.” Charlie Musselwhite lauds him as a serious player who investigated everything to “the Nth degree.” His recollection of their first meeting in Chicago underscores the inquisitiveness that fired Bloomfield’s curiosity about people and places.

From His Head…, which is unimaginatively chronological in its sequencing, sets off on the wrong foot with five tracks from Bloomfield’s 1964 audition for John Hammond, an abandoned session that was hopelessly marred by his singing. Musselwhite was on the date and in a 1994 edition of Bloomfield Notes remembered it as unrehearsed, “pretty sloppy…just real chaos.” Despite earnest efforts, Bloomfield’s vocal timbre and phrasing never met the basic requirements of the blues and gospel traditions he otherwise glorified with his impassioned playing and storytelling. And it’s odd that he persisted, for notwithstanding his guitar-hero status, he was always quick to acknowledge blues as first and foremost a vocal idiom.

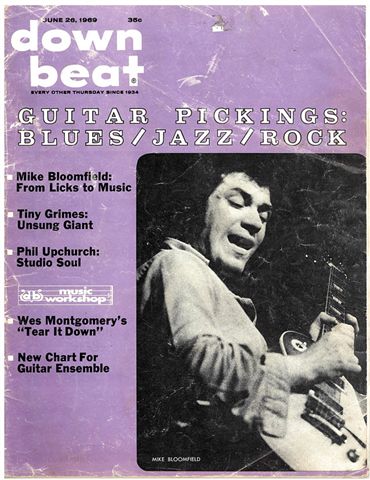

Bloomfield’s vaunted debut is also a textbook example of how unconvincing even the most skillful musicians can sound playing blues, and why it was the highly disciplined Butterfield Blues Band, with its frontman’s idiomatic singing and harp playing, and the seasoned rhythm section of Jerome Arnold and Sam Lay, that set the new standard among aspiring young players. To be sure, Butterfield’s pace-setting achievement benefited from Bloomfield’s brilliance, but it was the harpist’s intense, no-nonsense leadership that offered Michael a well-defined setting in which his virtuosity could flourish, both on standard blues structures like “I’ve Got a Mind to Give Up Living,” (a devastating tour de force that’s inexplicably missing from the Kooper production), and the groundbreaking blues raga, “East West,” the 13-minute instrumental that introduced Coltrane-like modality into the world of amplified, guitar-driven music.

“East West” is here, but it’s one of only three cuts by the Butterfield Blues Band, whereas one-third of this set’s bulk, the entirety of disc two, is devoted to Bloomfield’s erratic studio and concert recordings with Al Kooper. While their collaboration produced his biggest-selling album, Super Session, its finest moment, “Albert’s Shuffle,” barely equals his astonishing work with Dylan, Butter, Gravenites, and the Flag. In the oral history, Michael Bloomfield: If You Love These Blues, by Jan Mark Wolkin and Bill Keenom, Bloomfield refers to the collaborations with Kooper as “scams…a huckster’s idea that worked,” and adds, “I don’t think the playing is so hot.” He famously abandoned their L.A. studio session with only half an LP in the can, but later acceded to Kooper’s request for a makegood series of concert dates in San Francisco and New York. In the midst of the former, Bloomfield was hospitalized for insomnia-driven exhaustion and had to be spelled by Santana and Elvin Bishop; at the latter, he seemed most eager to showcase his latest discovery, Johnny Winter, who was signed by Columbia immediately afterward.

Kooper dismisses his colleague’s disavowals as evidence of an aversion to success, quipping that Michael ran less from “hellhounds” than from “hard cash on his trail.” Bloomfield died in 1981, but he was frankly outspoken in his lifetime, and it’s hard to imagine him not objecting to 15 of the anthology’s 43 tunes being drawn from his Kooper union. (None of his other collaborations are represented by more than 4 titles.) Put simply, From His Head…suffers from its producer-curator’s self-indulgence. That’s not to dismiss Kooper’s effort altogether; in today’s market, it’s doubtful anyone else would have got the industry go-ahead to bring this to fruition, and any effort at maintaining Bloomfield’s precedent-setting role in blues-rock has merit. Still, the set was done at minimal expense, and with the exception of the Butterfield and Muddy Waters sides, it’s drawn exclusively from Columbia’s vaults.

With a little extra spending and sleuthing, From His Head…could have gone much further in reflecting Michael’s wonderfully varied output, the range of which is virtually unparalleled among blues-rock guitarists. Less Kooper; a select few of Michael’s takes on classic blues and rags; and a sampling of his work with Big Joe Williams, Sleepy John Estes, Eddie Boyd, James Cotton, Sam Lay, Mitch Ryder, Chuck Berry, Barry Goldberg, Mother Earth, Maria Muldaur, Eddie “Cleanhead” Vinson, and Woody Herman, none of which is heard in the collection, is what his legacy deserves. (“Hitchhike on the Possum Trot Line,” above, is the masterpiece from his guest appearance on Herman’s 1971 Fantasy release, Brand New.)

What is included, however, is a bizarrely incomplete “Killing Floor,” the Howlin’ Wolf original that opened The Electric Flag’s 1968 debut, A Long Time Comin’. Here it’s missing Peter Strazza’s tenor saxophone solo, which makes no sense whatsoever. I suspect it may have been edited for radio airplay purposes when the record was released; the edit shortens it to under 4 minutes. But in that case, one can only wonder if Kooper was familiar enough with the Flag original to know the difference? Surely he didn’t order the cut? In any case, coming as it does right after “East West,” the solo’s absence obscures the continuity of modal jazz elements that Bloomfield’s music maintained after he left Butterfield early in 1967.

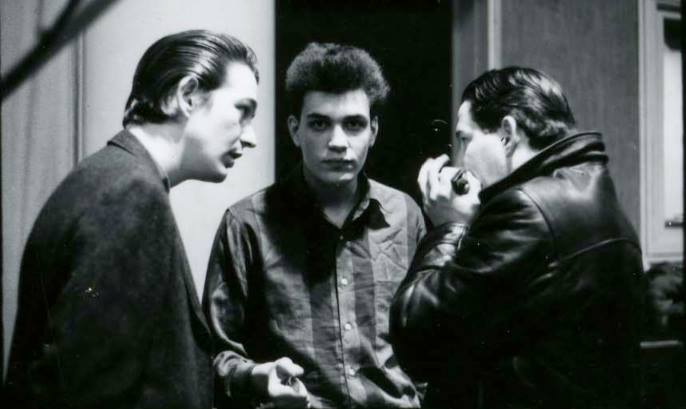

Like Kooper, who’s long said that merely hearing Bloomfield “warm up” at the Highway 61 session brought his guitar-playing career to a screeching halt, Dylan was deeply impressed by Michael’s playing the first time they met in Chicago in 1963. Two years later, he recruited the largely unknown 22-year-old to play the hot licks and turnarounds on “Like a Rolling Stone,” then deputized him to put together the band that backed his electric debut at Newport. He expected Bloomfield to anchor his new touring band as well, but Mike stayed committed to the bluesier course he’d embarked on before he was out of his teens.

As it happened, Dylan hovered over Bloomfield’s career from near its action-packed beginning all the way to its dissolute end; midway through, he tried to interest him in playing on Blood on the Tracks. From His Head to His Heart to His Hands concludes on a poignant note as Dylan introduces Bloomfield at the Warwick Theater in 1980, only a few months before the guitarist would be found dead from a drug overdose in the back seat of his car in San Francisco. Dylan is notorious for letting his singing do the talking on concert stages, but on this night he was downright effusive as he movingly recounted his earlier encounters with the man he’s curiously maintained would still be alive if he’d chosen to work with him rather than Butterfield.

Click here to hear an excerpt of the intro, and listen below as Michael joins Dylan on “The Groom’s Still Waiting at the Altar.” Alas, it proved to be the 36 year-old’s swan song. And as From His Head…will most likely be the swan song of Michael Bloomfield’s recorded artistry on a major label release, its producer’s errors, omissions, conceits, and uncertain intentions are all the more lamentable.