There’s a big new feature on Bonnie Raitt in the San Diego Union-Tribune in which she goes in-depth and mentions numerous influences, including the legendary Judy Roderick. I’ve been a fan of Judy’s since my high school days and keep going back to her great Vanguard album, Woman Blue. I also still wonder over who lifted my copy of her 1964 Columbia debut, Ain’t Nothin’ But the Blues, though I don’t miss it as much as I would Woman Blue. Judy’s first release was marred by a phenomenon that occurred way too often back in the day: obbligatos by wailing harmonicas. And producer Bobby Scott added a trad jazz combo on several selections that may have been at the heart of the dispute that led Roderick away from Columbia before she’d made a follow-up album. (As long as I’ve mentioned Scott, a pianist and music phenom in his own right, let me add that he played briefly with Lester Young and wrote one of the most moving narratives ever published on what it was like to work with Pres. It’s included in The Lester Young Reader under the title, “The House in My Heart.”)

By contrast, Woman Blue was a smartly produced collection that matched Judy’s crystal-clear voice and sophisticated phrasing with good tunes and spare accompaniment by Artie Traum and Russ Savakus. It’s a quiet album loaded with powerful material, and it feels deeply personal, even though most of the songs are non-originals. “Born in the Country,” an adaptation of Rabbit Brown’s classic “James Alley,” makes clear her bonafides as a blues stylist. How many white, 22-year-old suburbanites could declare “You won’t get past my 38,” and “It’s your own goddamn fault,” so musically and with such conviction? This performance alone places her in my small pantheon of whites whom I feel moved by as blues singers.

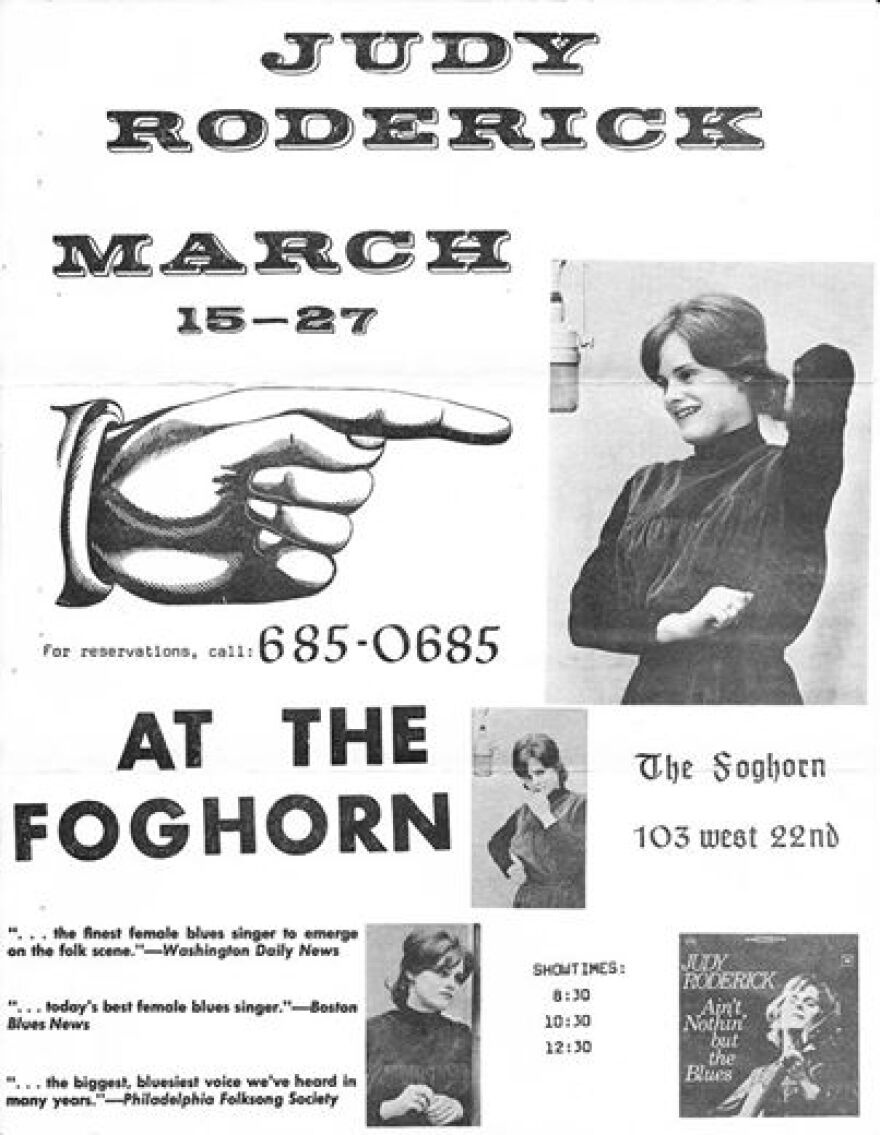

Born December 14, 1942, Judy was raised in Wyandotte, Michigan, and Elkhart, Indiana, went to college in Boulder, and made a strong impression on the Greenwich Village folk scene in the sixties. Dave Von Ronk, the so-called “Mayor of MacDougal Street,” said she was the first, the best, and the most original of his generation of white blues singers, and he grouped her among the “outsiders” who came to New York and “clawed” their way right past the natives. Judy returned to Colorado in 1969, then settled a few years later in Missoula, Montana, where she sang with the jazz/folk group, the Big Sky Mudflaps. Diabetes hastened her death at age 49 in 1992.

From start to finish, Roderick displayed an admirable sensitivity to blues feeling with a style that ranged from sweet to sassy, and a wide-ranging repertoire that drew on folk ballads, classic blues, swing tunes, and New Orleans barrelhouse. Here she sings “My Mother’s Son-in-Law,” the same tune Billie Holiday recorded at her debut session in 1933. Dee Dee Bridgewater and Christian McBride had a ball with it a few years ago on Dee Dee’s tribute to Lady Day. I don’t know the origins of this performance by Judy, nor if it’s been released on record. It’s identified here as part of her Lost Reels.

Village Voice columnist Gary Giddins hailed Roderick’s early eighties New York appearance with the Mudflaps while noting his disappointment that in the three shows he heard over the course of two nights, she sang only two tunes per set with the instrumental-oriented group. That was one of the few mentions Judy garnered anywhere after Woman Blue’s commercial prospects were vanquished by the sudden popularity of folk rock in the mid-sixties. She made a stab in that direction during her Colorado years when she sang and wrote songs for 60,000,000 Buffalo. Their 1972 Atco release, Nevada Jukebox, was produced by Ahmet Ertugun but went nowhere, It includes what sounds like Judy’s wishful desire to return to her roots.

That was pretty much it for commercial releases during Roderick’s lifetime. In 2008, a posthumous collection, When I’m Gone, was released by Dexofon. I found it at Louisiana Music Factory in New Orleans a few years ago, most likely in their stacks because it includes four titles from a session with Mac Rebennack (Dr. John), along with eight by her Missoula colleagues, The Forbears.

Dick Waterman wrote a liner note essay for the collection in which he recalled seeing Judy at Club 47 in Cambridge in the mid-sixties and his shock at hearing what “seemed like someone else’s voice coming out of this woman with the petite frame…dressed like a Sarah Lawrence student about to do lunch with other proper young ladies from Westport…It taught me that seeing is not believing but hearing is for real.” He added that at an exhibit of his photography that included an image of Roderick, few took notice of her except for a man who said, “She looked small but she played big.”

Here’s Judy singing “Mama Keeps Her Man at Home,” the prototype for “Denver to Dallas,” from Woman Blue.

Gary Giddins says Judy impressed him in the mid-sixties as “the most convincing white blues singer since Lee Wiley,” and writing in 1981, added that “no one in the intervening years has changed my mind.” Bonnie Raitt told the Union-Tribune she was “knocked out” by her, and that’s what emcee Peter Yarrow promised listeners 53 years ago at Newport ’64. For all of the gems that surface on YouTube, and of course, for Woman Blue, here’s to Judy Roderick, a rare trouper who kept it real.