I’m thinking about Greater Boston today, not only because of the Marathon and the Red Sox annual forenoon first pitch, but because it’s Patriot’s Day and Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Concord Hymn,” which was read at the dedication of the Old North Bridge in 1836, has been a favorite poem of mine since grammar school. The Old Manse, Walden Pond, Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, the Minuteman statue—all were destinations beginning in my teens, and my first day behind the wheel involved a drive to Concord then a zigzag back down the Old Connecticut Path to see the Paul Butterfield Blues Band at Nichols College in Dudley. I was drawn to Charles Ives’ “Concord Sonata,” the most challenging piece of music I’d heard at that time, with its dedication to Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne and the Alcotts, and hardly a day goes by that I don’t dip into the writings of Emerson, often just for an aphorism like “The sky is the daily bread of the eyes.”

When I interviewed Max Roach in 1978, he borrowed the most famous phrase from “The Concord Hymn” to describe the impact of hearing Charlie Parker for the first time on Jay McShann’s 1941 recording “Hootie Blues.” He said, “It was like ‘the shot heard round the world’.”

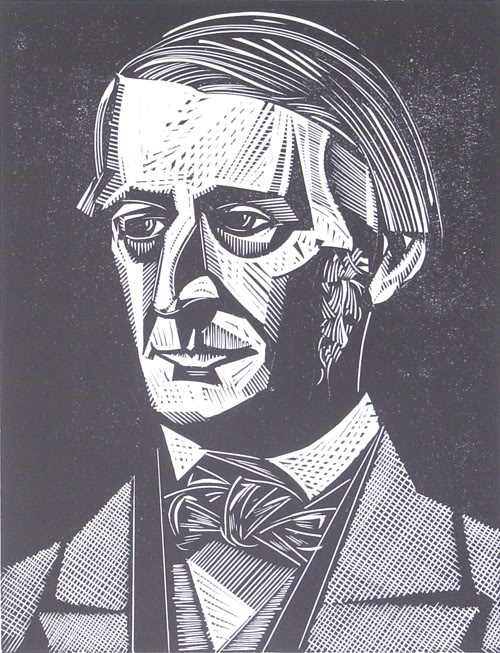

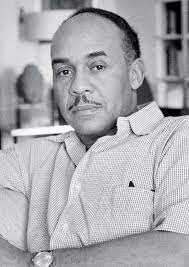

In his 1837 Phi Beta Kappa address, The American Scholar, Emerson urged Americans to establish a new cultural identity independent from Europe. Oliver Wendell Holmes called it the “Intellectual Declaration of Independence.” But while Emerson later supported John Brown and abolitionism, he failed to observe the presence or validity of a home grown culture, what his spiritual descendant Ralph Waldo Ellison called the “specifically American cultural idioms.” that slaves and their descendants were creating in his midst.

In an interview with the Massachusetts Review in 1976, Ellison said, “Given the reality of slavery and the denial of social mobility to blacks, it is ironic that they were placed by that very circumstance in the position of…being culturally daring and innovative because the strictures of ‘good taste’ and ‘thou shall-nots’ of tradition were not imposed upon them. And so, having no past in the art of Europe, they could use its elements and their inherited sense of style to improvise forms through which they could express their own unique sense of American experience. They did so in dance, in music, in cuisine and so on, and white American artists often found [African Americans’] improvisations a clue for their own improvisations.”

A decade later, Ellison told Alfred Kazin, “I can’t forget Emerson’s powerful force…[His] voice rang loud in Negro communities and influenced my own elders’ decision to seek a broader freedom out in the [Oklahoma] Territory. Emerson got to me in the classroom no less than at home; in drug store, in barbershop, and dentist’s chair, as well as on the playing field. He was also a spur to some of my father’s white friends, and thus sponsored a community of hope.”

Emerson extolled Shakespeare, Goethe and others in his 1850 publication, Representative Men. Had he been around a century later to write an addendum, I’d like to think Duke Ellington would have made the cut. Wouldn’t Emerson have appreciated the profound democratic spirit that infuses Duke’s work, both in the way he utilized the individual musical personalities of his band members, and in his embrace of the high and low, the sacred and profane, the refined and the funky– in short, the multi-cultural vitality of America? Ellington’s fascinating stylization of the American vernacular supports Ellison’s claim for African Americans’ central place in the nation’s identity, while his idiosyncratic originality as a composer and orchestrator echoes Emerson’s notion of self-reliance, a trust in one’s own creative instincts and ideas.

In 2004, when I visited the venerable literary critic, jazz fan, and Emersonian Harold Bloom, I was eager to ask him if he thought the Sage of Concord would have been receptive to jazz. Here’s an excerpt from our conversation.

“Well, you might at first think no. But we should never forget something about Ralph Waldo Emerson. In the entire history of literary criticism, the thing never to forget about Emerson is that, as a practical literary critic, he passes the ultimate pragmatic test. He is the guy who gets in the mail one day, in 1855, this weird-looking book. Leaves of Grass. The first edition. The very first copy of it. Designed by, printed by, the type set by, Walt Whitman. He gets this mad thing in the mail. He opens it, he starts to read, he reads it, he rereads it, and he rereads it again. And he writes that magnificent letter, which, as Edmund Wilson once said, is the real shock of recognition. [In it] he says, ‘I greet you at the beginning of a great career.’ And he also says of Leaves of Grass, ‘It is the greatest piece of wit and wisdom brought forth in America.’ A man who is capable of that…the man who is capable of getting Leaves of Grass out of the air like that and acclaiming it for what it was is a man who surely would have been capable of walking in and hearing jazz.”

Bloom’s Cornell classmate Whitney Balliett famously described jazz as “the sound of surprise.” Harold concluded our conversation with an earlier allusion to surprise. “It was Emerson who invented the phrase, ‘a stairway of surprise.’ That emphasis on surprise. High jazz, be it Armstrong or Parker or Powell or Mingus or the President [Lester Young]– high jazz is Emersonian.”