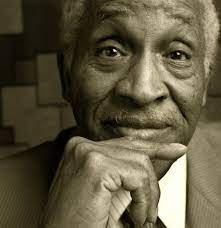

Von Freeman’s been on my mind lately. I knew the 88-year-old saxophonist was no longer in action, but he’d become so emblematic of Chicago jazz that in anticipation of a trip I’m making to the Windy City next month, I listened to his recordings Doin’ It Right Now and Serenade & Blues over the weekend. Alas, Von died early Sunday morning at age 88. The Chicago Tribune’s Howard Reich paid him proper respect yesterday with this 2700-word obituary. I’ll offer my own tribute to Vonski tonight and tomorrow in Jazz a la Mode.

On my last visit to Chicago in 2004, I was planning to see Von at his regular Tuesday night venue, the New Apartment Lounge on the South Side. But a few nights earlier, as I walked through the Loop with my sister and brother-in-law to see Karrin Allyson at the Jazz Showcase, who should I spy alighting from a car but Vonski himself. I’d already gotten a taste of little-village Chicago earlier that day when I ran into trumpeter Malachi Thompson on a back street; now here was another Chi-town legend before me. I stopped to say hello and asked Von where he was going with his leather-cased tenor, but when I told him I was already planning on a pilgrimage to East 75th Street a few nights later, he said, “Wait till Tuesday. Tonight’s for tourists.”

So with Michael Jackson, the English-born journalist and photographer who covers the Chicago scene as my guide, I made my one and only visit to the New Apartment on May 11, 2004. (I also heard Von in person in New York and at UMass, where he played a concert with Yusef Lateef around 2002; a decade earlier they’d recorded this session on Lateef’s YAL Records.) The club was in a fairly desolate area of the South Side, but the 75th Street block, most likely in recognition of the Mecca it was to jazz fans, was well-lit and the first thing that caught my eye was a street sign reading, “Von Freeman Way.” The lounge itself had a horseshoe-shaped bar which faced a low-rise bandstand occupied by Von’s sidemen, guitarist Mike Allemana, bassist Jack Zara, and drummer Michael Raynor. Freeman stood out front on the floor level with the rest of us, and without the benefit of a microphone, he filled the room with one of the biggest, most blues-drenched sounds I’ve ever heard.

Muhammad Ali’s famous taunt, “Float Like a Butterfly, Sting Like a Bee,” comes to mind as I think about Von’s tenor style, one he developed out of the dual influences of Lester Young and Coleman Hawkins. Freeman, who said he “got all this music by osmosis,” credited a little-known tenor player named Dave Young with forging a model synthesis of Hawk and Prez. Von met Young when they were stationed at the Great Lakes Naval Station during World War II, and he described his influence in a story for the Chicago Tribune:

“[Dave Young] had this sound that I had been looking for all my life,” said Freeman. “Because I loved Prez, but he didn’t have that power. He had a relatively soft tone, though beautiful. And Coleman Hawkins had all this power — man, he could blow. You could hear him around the block, but he didn’t have this floating thing of Prez’s. But when I heard Dave Young, he had the power and floating sound, like Lester, and that’s what I wanted to try to get.”

Here’s an example of what Von got as he locks horns with fellow Chicagoan Clifford Jordan at the 1988 Chicago Jazz Festival.

Happily, Von also got increasing amounts of official recognition from the City of Chicago; an honorary degree from the University of Chicago; and in January he was a recipient of the NEA Jazz Masters Award, the most select honor for a jazz artist in the U.S.A. But it was all a long time coming. Freeman labored for years in obscurity, and it wasn’t until Rahsaan Roland Kirk urged Atlantic Records to make an album on him that he finally made his first date as a leader, Doin’ It Right Now. That was in 1972, when Von was 49, but a fairly steady stream of recordings followed, all but one for tiny independent labels, but enough to keep his name before the cogniscenti while allowing him the freedom to pursue his own thing. Freeman’s pitch shadings, which the uninitiated would call “out of tune,” gave his style its signature and reflected his immersion in the highly-vocal, microtonal pitches of the blues. It also fairly defined him as a pure jazzman.

In 2004, Freeman told All Things Considered that his only regret was that his mother, who died in 1998 at age 101, “didn’t live to see” the late-career recognition he received. “That makes me almost want to cry,” he said, “’cause she never really wanted us to play music, but after we [Von and his musician brothers Bruz and George] behaved ourselves to a certain extent, she was proud of us. And she stuck it out with us, and she never saw any of us really make it, you know. And now– I don’t think I’ve made it, but, I mean, at least I’m being sought after for this 15 minutes.”