Donald Byrd, who died on February 4 at age 80, came to prominence in the mid-Fifties with bands led by Art Blakey, Horace Silver, and George Wallington. His frontline partner with Blakey and Silver, and on several of their respective recordings as leaders, was Hank Mobley. Leonard Feather hailed Mobley as the “middle-weight champion” of the tenor saxophone, a champ to be sure, though not quite in the heavyweight ranks of Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane.

Byrd was similarly endowed, a gifted trumpeter who was often quite impressive, and who became a dependable first-call player for jazz dates in the late ’50’s. Still, Byrd lacked the poetic mien of Miles Davis, the lyrical brilliance of Clifford Brown, and the brash eloquence of Lee Morgan. By the time Freddie Hubbard emerged in the early Sixties, Byrd seemed comfortably secure as a middleweight, and his recordings throughout that tumultuous decade reflect the work of a player who’d decided to leave adventure and experimentation to others while he stuck to the basics of soulful hard bop.

What Byrd increasingly embodied was a populism rooted in blues, the church, and soul music, a penchant for naming tunes in the vernacular guise of “Pentacostal Feelin’,” “Soulful Kiddy” and “Funky Mama,” and recordings that incorporated gospel choirs and other vocalisms. He called his 1963 recording, A New Perspective, which included Duke Pearson’s “Christo Redentor,” a “modern hymnal.”

As an African American whose middle name honored Haiti’s iconic independence leader, Donaldson Toussaint L’Ouverture Byrd II embraced principles of black economic empowerment and acted upon them both as a bandleader and as an educator when he began teaching in the late ’60’s. Howard, North Carolina Central, and Delaware State were among the groves where he established jazz studies programs, and he joined other academics and black nationaalists in seeking to define jazz less as a universal art form and more as a bright flowering of the black cultural continuum, “a lily in spite of the swamp,” as Archie Shepp saw it. In 1973, Byrd set down a veritable thesis along these lines with his jazz-funk recording, Black Byrd. Illustrated with an historical image of 19th Century black musicians, BlackByrd made the Hot 100 and became Blue Note’s biggest selling LP ever. Forty years since its release, it still stands as the most enjoyable and fully-realized fusion of jazz and electric funk.

In the wake of BlackByrd’s success, Byrd bristled at criticism from jazz critics for cashing in, but as the Penguin Guide respectfully puts it, he didn’t sell out so much as he “bought-in” to funk. And in addition to his own work in this dance-oriented fusion of jazz and black pop, he organized some of his Howard University students into a band called the Blackbyrds and produced a series of singles on them including the Top 10 hit, “Walking in Rhythm.”

Notwithstanding this success, Byrd maintained a hostile and defensive attitude toward critics who questioned his work, and fusion in general. The New York Times obituary quotes him from a 1982 interview: “Then the jazz people starting eating on me. They had a feast for ten years…Everything’s that bad was attributed to Donald Byrd. I weathered it, and then it became commonplace.”

Which? The criticism? Or the style? If he meant the latter, I would argue, not exactly. While Byrd pursued his brand of fusion, most of the players he’d grown up with in Detroit’s musical hothouse of the ’40’s and ’50’s remained stalwarts of modern jazz. Even Byrd returned to more straight-ahead undertakings in the ‘80’s on a couple of dates produced by Orrin Keepnews, but by then he’d largely lost his proficiency as a trumpeter. In 2000, he was honored as an NEA Jazz Master.

We’ll hear Byrd’s great work of the 1955-’67 period in tonight’s Jazz a la Mode, including his recordings with Blakey, Silver, and Wallington, Sonny Rollins, Sonny Clark, and John Coltrane, his appearance with Thelonious Monk at Town Hall in 1959, and with his Motor City sidekick Pepper Adams at the Five Spot.

For additional perspectives on Byrd, read these obituaries by the Detroit Free Press, the Guardian, and the Washington City Paper. The latter mistakes him as the composer of “Christo Redentor,” but has more detail on Byrd’s establishment of a jazz studies program at Howard.

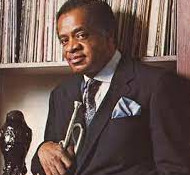

Here’s Byrd at Cannes in 1958 with his quintet featuring flutist Bobby Jaspar, pianist Walter Davis, Jr., bassist Doug Watkins, and drummer Art Taylor playing “I’ll Remember April.”