Paul Combs dedicates his new biography of Tadd Dameron to four jazz greats who “made [him] promise that [he] would see this project through.” Combs’s challenge was formidable, and he admits that he “had no idea what [he] was in for” when he undertook the task of writing about Dameron, but there’s apparently extra incentive when it’s Dizzy Gillespie, Charlie Rouse, Art Blakey, and Harold Vick who’ve urged you on. Now it’s complete, and what’s been a labor of love for 25 years stands as a comprehensive look at one of jazz’s foremost composers and least documented figures. The undertaking was especially challenging, for notwithstanding the extensive acknowledgments that Combs makes to dozens of sources, Dameron himself was a very private man and there was little in the way of correspondence and other memorabilia with which to put flesh on the bones of his life.

Combs writes, “While some readers might criticize my efforts to come to an understanding of Dameron’s state of mind at various times in his life, educated guesses are unfortunately our only recourse.” In this and other regards, Combs proves to be a sensitive and perceptive observer of the man, and his analysis of scores of Tadd’s compositions and recordings makes Dameronia an admirably complete work.

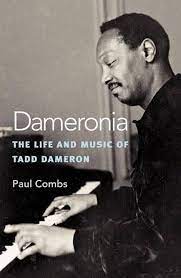

(photos by William Gottlieb)

Birth of the Coolconception, as well as the small band writing of Gigi Gryce, Horace Silver, Frank Foster, Quincy Jones, and many others.

France was a tonic for Dameron, and the sojourn inspired some of his most ambitious writing, including the long form “Fontainebleu,” which he recorded in 1956. But by the early 50’s, his fortunes were in decline, and so too the scene itself. Combs writes, “A sort of terrible gloom had fallen over the community of younger jazz musicians by the end of 1950…Fifty-second Street had gone to strip joints, Bop City had closed, and there were not even big bands to play in anymore. Tadd and Miles had been treated with respect and admiration in Europe…only to return home and have the feeling that few people cared about their skills and accomplishments.”

Drug use didn’t help either. Notwithstanding the overdose death of his trumpet-playing friend Freddie Webster in 1947, Dameron apparently began using heroin the following year and addiction plagued the rest of his career, resulting in arrests and prison terms, and requiring long retreats back home to Cleveland. Combs acknowledges that where Webster’s and Fats Navarro’s drug-related deaths might have spelled a “wake-up call” for Tadd, “addiction is not a particularly logical phenomenon.” Dameron later suffered from cancer over the last few years of his life and died in 1965 at the age of 48, a largely forgotten figure.

Benny Golson, who wrote a sweetly affecting foreword for the biography, worked with Tadd in Bull Moose Jackson’s jump blues band in the early fifties. An assignment like this was a stepping stone for a young player like Golson, much as it was for many other jazz greats at the outset of their careers. For an established figure like Dameron, however, it could only have spelled the reverse. Still, Golson remembers that after “our first rehearsal, when he had a chance to hear me play, he eagerly approached and, with a spirit of excitement, told me how impressed he was with me…This meeting and our relationship would set the course of my career.”

Dameron has long been hailed as the romantic among modern jazz composers, and Combs makes note of his remarkable ability at keeping the chaos and conflict in his personal life out of his music. Writing of his session with Coltrane, he says, “When one considers the state of Dameron’s personal life at this time, it is striking that his music maintains a kind of serenity, in spite of the chaos and strife that surrounded him. In this, he is like Mozart…Some artists use their art as a cathartic outlet for the emotional elements of their lives; others, such as Dameron, use it as a sanctuary.”

I’ve often thought that the brilliant musicians Dameron worked with have been a mixed blessing for his legacy. Over time, sidemen like Navarro, Clifford Brown, and John Coltrane rose to heights that tended to obscure the prestige Dameron enjoyed as a bandleader back in the day. Navarro was a member of Tadd’s ensemble between 1947-’49; Brownie recorded with Dameron’s orchestra in 1953; and in 1956, a pivotal year in Coltrane’s career, he was showcased on Dameron’s Prestige date, Mating Call. The great studio sides Dameron made with Navarro and the air checks of his sextet at the Royal Roost invariably appear under the trumpeter’s name; with Brownie’s tragic death in 1956, the session known as A Study in Dameronia was subsumed under the title, The Clifford Brown Memorial Album; and the date with Trane has long been co-credited as his and Tadd’s.

Beyond the scope of his recorded legacy, it’s the enduring appeal of Tadd’s compositions that keeps his music alive today. Thirty years ago, two ensembles, Dameronia and Continuum, the former founded by drummer Philly Joe Jones, the latter by Slide Hampton and Jimmy Heath, shed new light on Tadd’s music; in more recent years, Joe Lovano’s Nonet has recorded at least seven of his originals. Lovano’s connection to Dameron extends beyond their common background in Cleveland; Joe’s tenor-playing father, Tony “Big T” Lovano, played with Dameron in 1955 at Cleveland’s Club Congo.

Tadd’s work has also been showcased on trio sessions led by pianists Barry Harris and Tardo Hammer. Shortly before their recent deaths, James Moody and Hank Jones combined sensibilities for a pair of recordings that included six Dameron tunes. Numerous Dameron originals, among them “Good Bait,” “Our Delight,” “Soul Trane,” “If You Could See Me Now,” “On a Misty Night,” and “Hot House,” live on as jazz standards.