There’s an aspect of Muddy Waters’ birthday that reminds me of Louis Armstrong. In the 1980s, documents surfaced that disproved Armstrong’s claim of a birth date of July 4, 1900. As his baptismal certificate revealed, Satchmo was born on August 4, 1901. But as dubious as many had been over the Independence Day notion, no one really pressed the matter, not least because the date seemed perfectly appropriate, however apocryphal, for the man who transformed music in the American Century.

Muddy Waters, the most famous son of the Mississippi Delta, was born McKinley Morganfield on April 4, 1913, in Jug’s Corner, near Rolling Fork, and was raised on the Stovall Plantation near Clarksdale. Muddy’s marriage license and musician’s union applications both state 1913 as his birth year, and when John Work interviewed him in 1941 for the Library of Congress, for whom Muddy made his first recordings, he wrote “Rolling Fork 1913” in his field notes. But in 1955, Muddy told the Chicago Defender that he was born in 1915, and he stuck to that date for the rest of his days. And so apparently has his family.

As even regal figures have vanity issues, I’m surprised he didn’t shave off more. Peter Guralnick, in a profile written in 1970 and published in Feel Like Going Home, said, “He is, it is obvious, an extremely proud man, and sometimes it is not difficult to imagine that the titles which have been bestowed upon him for his singing were not in fact his by earlier possession. For Muddy Waters carries himself with all the dignity of a king.”

As the man whose name is synonymous with Chicago Blues, Muddy presided over the South Side blues world for nearly four decades with a magnanimity that encouraged and promoted the talents of many sidemen, including Jimmy Rogers, Little Walter, Junior Wells, James Cotton, Otis Spann, Luther “Georgia Boy” Johnson, and Luther “Guitar Jr.” Johnson, as well as young white acolytes Paul Butterfield, Mike Bloomfield, and Charlie Musselwhite. As for personal vanity, as Warren Zevon famously said of a London wherewolf, “His hair was perfect.” And he made no secret of his preference in women, which he’d invariably mention when introducing a repertoire staple, “She’s Nineteen Years Old.” True to form, in 1976, three years after the death of his beloved wife Geneva, he married nineteen-year-old Marva Jean Brooks, a Floridian who apparently adored him but said she knew little of his stature until rock stars began calling at the family home in Westmount, Illinois.

Muddy Waters died on Saturday, April 30, 1983. Much as I’ll never forget the first time I heard the great bluesman, I’ll also remember how I got a feeling that he’d passed. That Sunday, as the deejay on WMUA’s Country, Blues & Bluegrass played a couple of his records back-to-back, I said to myself, “Muddy must have died.”

Now here it is Muddy’s centennial, and I’ve yet to see any attention paid to the milestone. Notwithstanding the evidence which Robert Gordon provided in his acclaimed 2002 biography, Can’t Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters, Muddy’s official website maintains the 1915 birth year, and everyone else seems to be following suit. If that’s the case, I’ll be celebrating it twice. Where Armstrong merits two annual birthday observances, let’s at least honor Muddy’s legacy with two centennials.

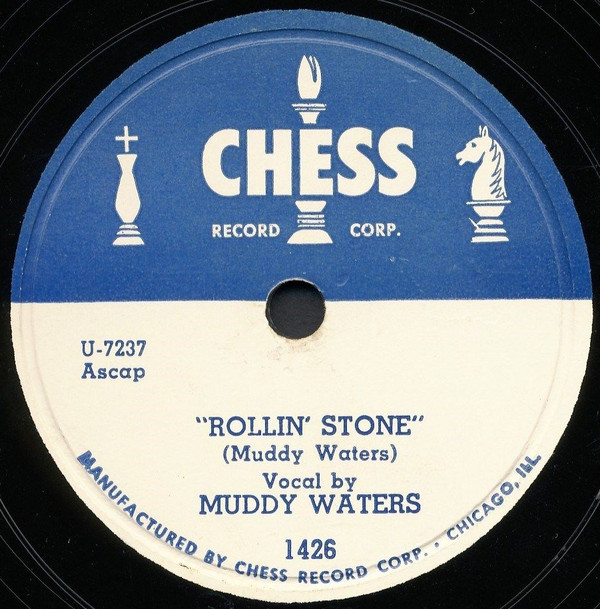

As for the first time I heard Muddy Waters, I was just about to leave the walkout basement of a Worcester three-decker where we used to hang after school when my friend Deb dropped the tone arm on a record she’d bought in the cut-out bin at Woolworth’s, sticker price 99 cents. It was The Best of Muddy Waters, and Side A began with “I Just Want to Make Love to You,” a 1954 recording that had all the basics of what made Muddy’s blues so deep and affecting: stop-time breaks; declamatory singing that combined swaggering charm with gruff insistence; Little Walter’s otherworldly chromatic harmonica; and what Muddy called a “big drop after-beat” that underscored the stunning tension and release properties of his music.

In that moment, I experienced what the literary critic Edmund Wilson called “the shock of recognition,” a term that Greil Marcus applied to hearing Robert Johnson for the first time. It would take me a few spins of The King of the Delta Blues Singers to really appreciate Johnson, but Muddy stopped me in my tracks and life has never been the same since. So thank you, Muddy Waters.

Over the years, I saw Muddy several times at venues in Greater Boston, including the two week-long engagements he played at Sir Morgan’s Cove in Worcester in 1972 and ’73. The first of these was one of the last dates he played with his funky Chicago outfit featuring guitarists Pee Wee Madison and Sammy Lawhorn and harp player Mojo Buford. Bob Margolin played guitar in the opening act, which was led by Worcester’s blues standard bearer Babe Pino, the singer-harp player who was a grammar school classmate of mine. Bob and Babe first worked together in the band that Luther “Georgia Boy” Johnson led in a long residency at the Highland Tap in Roxbury after he’d left Muddy in 1969. Muddy hired Margolin shortly after the Sir Morgan’s engagement and the Brookline native proved to be most adept at fitting in with Muddy’s unique style of behind-the-beat, “delay” singing. He’s been a loyal custodian of his musical legacy ever since.

Here in 1972 with the legendary George “Harmonica” Smith, and the players he was with at Sir Morgan’s, Lawhorn, Madison, Pinetop Perkins, Calvin Jones, and Willie Smith, he delivers one his signature boasts, “Mannish Boy.” That’s Madison playing the opening lick off-camera.

Muddy is well-documented on record, concert films, and YouTube. Here he is singing “The Same Thing” at Montreux, with Buddy Guy, Junior Wells, and Rolling Stone bassist Bill Wyman’s band. The close-ups of Muddy singing and clapping time make this late-career performance especially powerful.

Here’s Muddy closer to his prime singing “You Can’t Lose What You Ain’t Never Had.” It’s from a 1966 Canadian Broadcasting Corp television special devoted to blues. That’s James Cotton blowing harp and Otis Spann at the piano, along with Pee Wee Madison, bassist Jimmy Lee Morris, and drummer S. P. Leary.

Muddy was the centerpiece of the 1970 documentary Chicago Blues, which placed the music in the broader context of race, poverty, and urban desolation. In the film, he’s seen giving standout performances of “Hoochie Coochie Man,” and “She’s Nineteen Years Old,” at a small Chicago bar where he’s accompanied by Buddy Guy and harp player Paul Oscher, while off-stage he lays out a veritable manifesto on what it takes to sing the blues. “The type of blues I sing, you must pay the cost out there. You just don’t get up and walk the streets and get you whatever you want whenever you get ready and think you can sing the blues like myself, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Lee Hooker…Plus you gotta go to church to get this particular thing in your soul.”

Here in 1978 he sings “They Call Me Muddy Waters,” his signature song about the “most bluest man in this whole Chicago town.” He’d first recorded it with Little Walter in 1951, but 27 years later he’s still bringing a smile to the face of harp player Jerry Portnoy with his vocal and guitar inflections. This is the great combo that Muddy led between 1973-’79; in addition to the Chicago-born Portnoy, it includes Margolin and Luther “Guitar Jr.” Johnson; Pinetop Perkins, piano; Calvin Jones, bass; and Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, drums.