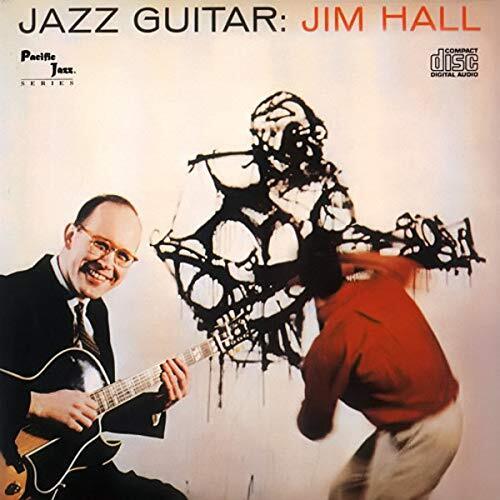

I think it was of Jim Hall that someone once mocked, “Funny, you don’t look like a jazz musician.” Whitney Balliett, whose New Yorker profile of the guitarist is one of his most personal and affectionate, said that, “[Hall] could easily be the affable son of the stony-faced farmer in ‘American Gothic’.” Hall, of course, belies any presumptions based on looks, and that includes skin color. From the outset of his career, black musicians including Chico Hamilton, Hampton Hawes, John Lewis, and Ella Fitzgerald sought him out. (Hall said Ella’s pitch was so perfect that he used her voice to tune his guitar.) In the 60’s, he was in seminal bands with Sonny Rollins and Art Farmer, and in 1972 began a musical partnership with bassist Ron Carter.

There’s a great deal of footage of Hall circulating on YouTube, including an hour-long documentary, A Life in Progress, which you can see by clicking here. The sampling on this page begins with a Sonny Rollins clip from the Jazz Casual series, which Ralph J. Gleason hosted on KQED in San Francisco. Hall played on Sonny’s 1962 release, The Bridge, which famously marked Rollins’s return to the scene after an 18-month sabbatical. This brilliant performance, which feels even more compelling than the studio original, was taped on March 23, 1962. That’s Bob Cranshaw on bass and Ben Riley on drums.

Next is an unusual clip in which we see Hall “auditioning” for the Merv Griffin Show Orchestra. After a bit of Merv’s shtick, Griffin and Hall play “They Can’t Take That Away From Me.” That’s Art Davis behind the shades; the bassist seems pretty impassive until Merv goofs with Hall about the key signature.

When I posted this on FB with the lead, “Man, what musicians have to suffer,” several comments came in, including dissents by pianist Eric Reed and saxophonist Russ Gershon. Russ, who leads the Either/Orchestra, said, “I think it’s actually a somewhat funny bit and Jim looks pretty amused, at least by his phlegmatic standards. I have no doubt that the guys in that band were delighted by the steady paycheck and by working for a boss who respected musicianship enough to have spent the time learning to play on a decent level…Playing a regular, short gig in a clean TV studio looks pretty good to me!”

Eric Reed wrote, “Based on several of the comments here, I expected to be repulsed – to my surprise, I was not. Lesson for me: read after viewing. Was this the ideal setting for a Jazz musician? Maybe not. But how many times have you ever witnessed any Jazz musician being singled out for this kind of attention on a major variety show? At the very least, it was in the idiom [of Jazz].”

Peter Blanchette, the renowned archguitarist from Northampton, added this appreciative note. “Jim Hall moves me like no other player. I saw him at Berklee Performance Center as a kid and he made me understand the power of understatement.”

Following his tenure with Chico Hamilton’s quintet with its “string section” of guitar, bass, and cello, Hall moved on to an even more unorthodox setting with the Jimmy Giuffre Trio featuring Bob Brookmeyer. This trio of saxophone/clarinet, valve trombone, and guitar was pictured in the opening frames of the Newport Jazz Fest documentary, Jazz on a Summer’s Day.

Hall has few peers when it comes to the art of improvised dialogue. Beginning with Undercurrent, his 1962 duo with Bill Evans, the guitarist made numerous sessions pairing him with pianists, bassists, and guitar players. It’s hard to find a review of the 1972 performance Alone Together by Hall and Ron Carter that doesn’t express astonishment over their telepathy. I missed that duo in person, but I’ve marveled over the amazing rapport between Hall and bassist Scott Colley on a few occasions. At the 2000 Montreal Jazz Festival, where Hall was showcased in concerts over the course of five nights, I heard him playing duets with bass legends Dave Holland and Don Thompson, and with saxophonist Greg Osby.

While most of the hoopla, including a Grammy nomination, at Sonny Rollins’s 80th birthday concert in 2010 was devoted to a surprise appearance by Ornette Coleman on “Sonnymoon for Two,” I’ll cherish most the memory of Rollins and Hall playing another from their early 60’s RCA series, “If Ever I Would Leave You.” Alas, Rollins’s birthday concert CD, Road Shows, Volume 2, doesn’t include their hard-swinging take on the Lerner and Loewe standard, but it’s preserved here on “Jazz Casual.”

As guitar players go, Hall found kindred spirits in Pat Metheny and Bill Frisell, both of whom also qualify as proteges. Hall and Frisell included a disc of duets on their Artist Share project, Hemispheres, and Hall’s daughter Devra made this knowing observation in the liner notes: “Bill’s eclecticism and Jim’s curiosities are old news, but what keeps them going is the unknown and the quest to find and share a common ground…These musical conversations…evoke myriad moods with tonal palettes, dissonances, and textured melody. Whether it seems to lead around the next bend and beyond, or over the moon and back, there is always a sense of home, an aural returning.” Here they are in 1995 playing Hall’s original, “Big Blues.”

I noted on this blog in March that Frisell was inspired by, and dedicated a composition to the artist Charles Cajori, who also died in December. Cajori and Leland Bell were among the original faculty of the New York Studio School. Hall played at Bell’s memorial service in 1991 and told Cajori it was the most challenging performance of his life. Of the Leland Bell works that I’ve seen, only two were portraits of musicians, one of Lester Young, who was his musical hero, the other of Jim Hall, who was his friend. (Thanks to Cajori’s widow, the artist Barbara Grossman, for sending the pdf of this image.)

[Note: I posted this tribute to Jim Hall on December 4, 2013, his 83rd birthday. Alas, with his death on December 10, it now doubles as a memorial. NPR’s Tom Cole spoke with Sonny Rollins and Hall’s proteges John Scofield and Julian Lage for this remembrance on Morning Edition. The New York Times posted this obituary of the guitarist by Peter Keepnews.]