I noticed a little row on Facebook yesterday over the extent to which Chico Hamilton’s affiliation with cool jazz was emphasized in his obituaries this week. The Times, for one, headlined its obit, “…Exponent of Cool Jazz.” Hamilton, who died on November 25 at the age of 92, surely followed the beat of his own inner drummer. But while his tenure with the paragons of West Coast Jazz, Gerry Mullligan and Chet Baker, was brief, their historical prominence makes it inevitable that he’ll long be identified with them. Moreover, beginning in the mid-50’s, by dint of both geography and stylistic uniqueness, Chico’s music offered a further elaboration on California cool.

Foreststorn “Chico” Hamilton was a Los Angeles native whose early models were Sonny Greer, Jo Jones, and Sid Catlett. Hamilton toured with Lionel Hampton in 1940, then served four years in the Army during World War II. When he returned to the scene in 1945, the new style of modern jazz drumming emphasizing polyrhythms and bold, percussive effects (“dropping bombs”) surprised and intrigued him. But Hamilton maintained a subtler approach that proved to be well-suited for his work with Lester Young, who preferred a softly propulsive “titty boom.” He also worked as the house drummer at the legendary Hollywood nightclub, Billy Berg’s.

In 1952, Hamilton became a charter member of the Gerry Mulligan Quartet, the group that inspired the coinage “cool jazz” and unwittingly fostered the racially-charged dialectic between West and East Coast jazz. (The Miles Davis Nonet recordings of 1949-50 were only later branded “The Birth of the Cool” out of respect for their historical precedence; Mulligan was a member of the short-lived nonet.) While Mulligan and Chet Baker were restless figures beset with demons, Hamilton was even-keeled and reliable. By this time, he also had a family to feed, and as his tenure with the quartet preceded the February 1953 story in Time that catapulted it to fame, “low pay” caused him to move on to a more lucrative job with Lena Horne.

In 1955, Chico established the first of his own bands, which for the rest of the decade were hailed for their innovative, chamber jazz orientation. Whitney Balliett called them “vaguely avant-garde.” Quintets were Hamilton’s norm, but with a “string section” comprised of cello, guitar, and bass, and a front line player doubling on clarinets, flutes, and saxophones, they bucked the bebop convention of trumpet, sax, piano, bass, and drums. And while the Mulligan Quartet famously eschewed the use of a piano, Hamilton elected to go through his entire career without those 88 tuned drums. One percussion instrument was enough for Chico.

Chico’s extensive use of brushes, mallets, bells, hands and fingertips added an exotic flavor to his work. He was among the most melodic and compositional of modern percussionists, and his albums were studded with solo pieces like “Happy Little Dance” and “Trinkets.” James Gavin, in his biography of Chet Baker, Deep in a Dream, likened Chico’s drumming to “Sammy Davis, Jr. doing a tap dance.” In West Coast Jazz, Ted Gioia cites a 1955 Metronome interview in which Hamilton says of the drum, “It is a very melodic instrument, very soft, graceful in motion as well as sound: a sensuous feminine instrument.” That’s a far cry from what Max and Blakey and Philly Joe were beating back east.

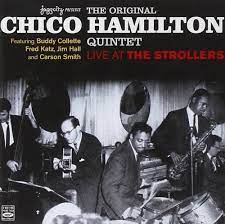

Hamilton’s inaugural group included cellist Fred Katz, guitarist Jim Hall, and bassist Carson Smith, along with the classically-trained multi-instrumentalist Buddy Collette. Successive bands helped bring to prominence saxophonists Eric Dolphy, Charles Lloyd, Paul Horn, and Eric Person, and guitarists John Pisano, Gabor Szabo, and Larry Coryell. Dolphy, like Collette, played flute, clarinets, and alto saxophone, and while his work with Hamilton only hinted at the harmonically daring approach he became renowned for, it provided him with an opportunity to experiment beyond the parameters of hard bop and traditional song forms.

Dolphy made his first appearances on the East Coast with Hamilton in 1958 and 59, and after leaving Chico and settling in New York, he joined forces with another L.A.-born trailblazer, Charles Mingus. Hamilton’s group with Dolphy performed at the Newport Jazz Festival in 1958 and was filmed by Bert Stern for his landmark documentary, Jazz on a Summer’s Day. Here introduced by Willis Conover, they play Chico’s original, “Blue Sands.”

In the oral history Central Avenue Sounds: Jazz in Los Angeles, Chico’s boyhood friend Jack Kelson compares him to Duke Ellington in that “he plays his music using any player, any group of instruments…He puts his stamp on it.” Speaking of which, in 1958, Hamilton became one of the first jazz artists to devote an entire album to Ellington’s music. However, Pacific Jazz owner Richard Boch was dubious of Dolphy’s commercial potential, and the album went unreleased for 42 years. In 1959, a reunion of Hamilton’s original quintet with Katz and Collette occasioned another date with Duke’s music which Pacific Jazz released asThe Ellington Suite. When the session with Dolphy was unearthed in London in 1995, Michael Cuscuna saw to its release under the title, The Original Ellington Suite.

Cuscuna posted a memorial tribute to Hamilton on the Mosaic Records website that concluded this telling recollection: “I got to work with Chico in 1975 on his second album for Blue Note. He took a fatherly interest in me (as he did in others). He was wise, funny and a good friend. I think the best advice he ever gave me was that when you are tempted to hang out all night with the guys, remember who really loves you and race back to your woman. She’s the only one that will always be there for you. His decades-old marriage to his late wife Helen was testament to that advice.”

From the Original, here’s Hamilton with the keening sound of Dolphy on alto; guitarist John Pisano, bassist Hal Gaylor, and cellist Nate Gershman, playing “In a Sentimental Mood.”