Alas, Aretha Franklin died on Thursday, August 16, three days after I posted the tribute below to the Queen of Soul. We listened to Ree for our three-hour drive to Cape Cod on Wednesday night and I could hardly contain myself. Hers is simply the most powerful and versatile voice of my lifetime. The line that’s resonated most this week is “If you walk in that door, I can get up off my knees,” from “Since You’ve Been Gone (Sweet Sweet Baby).” It reminds me of a to-the-point reflection sent by a 70-year-old female friend, “Boy, did she ever get me through some tough times.”

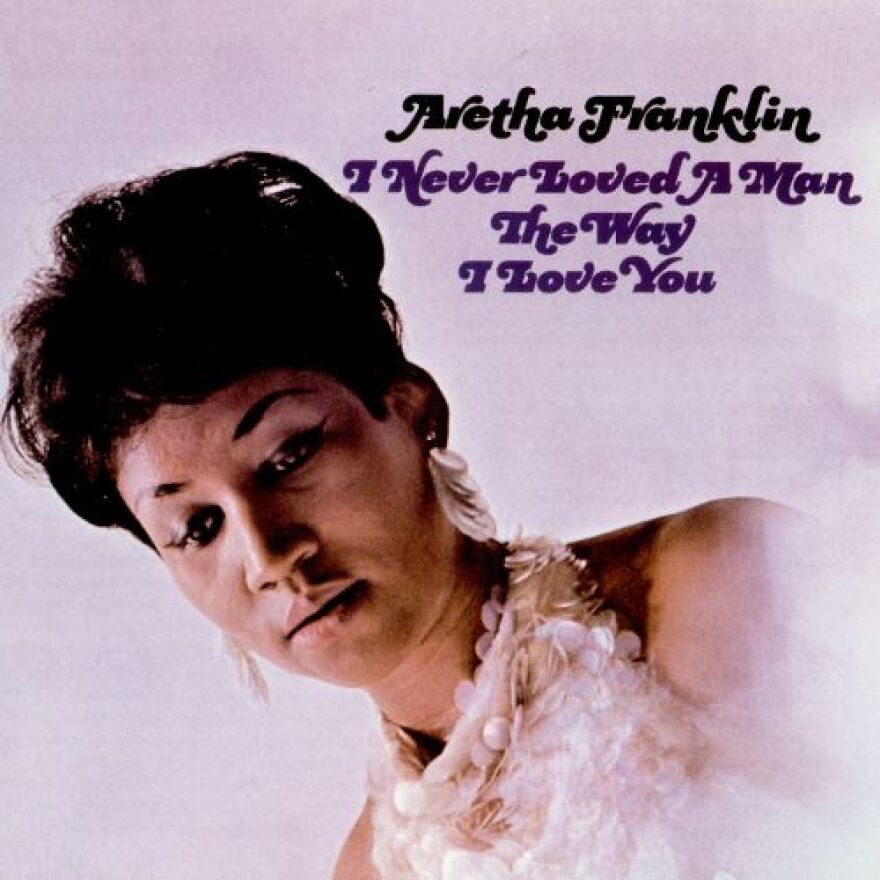

Aretha’s power lay not only in her deeply soulful voice, but in the blues and gospel harmonies that her piano playing emphasized and imspired her voice to soar. I was 14 when I became aware of Lady Soul through her breakthrough Atlantic hits, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You),” and “Respect.” She was my number one for at least the next half-dozen years. I became a fairly hardened blues and jazz convert during that period and found little to embrace on the pop charts, but let’s face it, there’s a particular vulnerability that virtually all teenagers face and the Top 40 aims for with laser-like precision. While I did my best to avoid it by hanging as deep in the grown-up musical alley as I could get, Aretha always pulled me closer to something resembling my true adolscent self. “Don’t Play That Song for Me (You Lied),” strikes me as the epitome of Ree’s unique skill at combining gospel gravitas and pop sentimentality, a unique blend that made her music, and soul music in general, so powerfully incisive and broadly appealing.

B.B. King’s version of “Night Life” from his 1966 nightclub LP Blues Is King has long been the definitive take for me on Willie Nelson’s classic blues. But Aretha’s beautifully sung and filmed performance of it in Sweden floors me now, especially with her added verse (@2:03) about how love exacts a high price from those who’ve lost, but “they might not have loved at all if they had known they couldn’t pay the cost.”

Like everyone else, I’m reflecting on Aretha Franklin tonight after getting word that she’s in grave health and has entered hospice care in Detroit. Ree wasn’t the first r&b singer to pull me in, but she’s been a favorite for over 50 years, and I regard her as the figure whose musicianship and storied background as the daughter of the famed Reverend C.L. Franklin made her the ideal conveyor of gospel-infused soul music to the mainstream. Ray Charles, Dinah Washington, Solomon Burke, Etta James and others paved the way, but Aretha took it to the masses. I first saw Aretha on Boston Common on September 15, 1971. (I checked today with a friend to ask if it was King Curtis who backed her that night? He thought so, but a comment made by saxophonist Scott Hamilton on my Facebook post about Aretha helped clarify that she was with King Curtis’s orchestra, the Kingpins, but Curtis himself had been murdered a few weeks earlier.) I saw the Queen of Soul next 32 years later, on June 7, 2003, at a concert in Hartford that I attended with a couple of friends who’d first seen her in the ’60s.

I’d first looked forward to seeing Aretha at the Newport Jazz Festival in July 1971, but a storming of the gates by hippies demanding free admission ended the fest before Aretha, Miles Davis, Duke Ellington and many others appeared that weekend. In his memoir Myself Among Others: A Life in Music, Newport producer George Wein wrote, “[Atlantic Records executive] Nesuhi Ertegun…noted that Aretha Franklin was especially sorry about the cancelled performance as she had rehearsed four new songs [on Saturday] afternoon.” She was scheduled to headline the Sunday afternoon bill with King Curtis, Roland Kirk, and Les McCann. She’d first played Newport in 1962 shortly after she’d signed with Columbia Records and was being groomed by John Hammond as a jazz-oriented pop singer. It would be several more years before “the true measure of her talent was…apparent to the uneducated ear,” as Wein put it.

That true measure of Aretha’s genius was discerned by Jerry Wexler, who knew it was all wrong that Columbia didn’t have her playing piano for herself over the course of the six modest-selling albums she made for the label. But here, three years before her Atlantic Records chart-topping debut, I Never Loved a Man the Way I Love You, she gives a strong hint of what was to come in this appearance on The Steve Allen Show. Note how guitarist Herb Ellis, who’d spent five years with the Oscar Peterson Trio, applauds her at the end of “Won’t Be Long.”

Here’s what I wrote after seeing her in Hartford 15 years ago: We saw Aretha last night at the Bushnell. She gave a spectacular 90-minute performance. Two keyboards, four back-up singers deputized occasionally as percussionists, a big band augmented by members of the Hartford Symphony Orchestra. Besides the latter, she called the names and hometowns of all the members, a nice touch à la Duke Ellington. Her son Teddy, a favorite of the ladies, plays real good guitar. On “Respect,” she sang “Ain’t gonna do you wrong,” then dropped a register to add a raspy, “Cause I don’t wanna.” There’s something about seeing masters like Ree add a little something extra that really raises the goose flesh. She opened with a blues, then sang “The House That Jack Built,” “Chain of Fools,” and “Ain’t No Way,” like she was taking part in a gospel caravan. She accompanied herself at the piano for “Spirit in the Dark,” which was pure church. On the ride down to Hartford we talked about Otis Redding and how much we all dug his ballads, so it really blew us away when she dropped “Try a Little Tenderness” on us early in the show. She is indisputably Lady Soul, one of the wonders of music, and she wasn’t resting on any laurels last night. She looked good, seemed to dig the Hartford vibe, engaged several of the front row patrons, managed some nice moves, and came stage left (about 15 feet from me) on just about every song. She laid an aria on us, and the pop standards “I’ll Be Seeing You,” and “If Ever I Would Leave You.” She sang complete versions of everything– no medleys. As she enters and departs, a video screen displays a photo album of her career, shots with celebs, with Jerry Wexler and the Ertugan brothers, a few with “our first black president,” as Toni Morrison calls Bill Clinton, and one with MLK that puts it all in perspective.