Working Through John Coltrane’s Influence

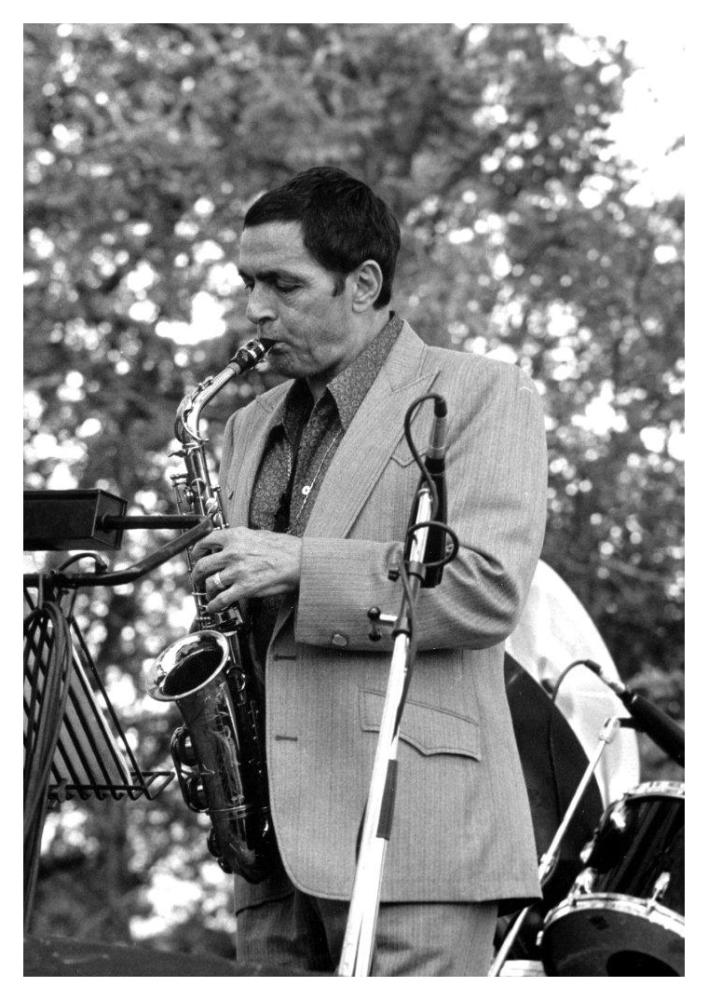

Art Pepper was born 90 years ago today in Los Angeles. The saxophonist’s life was scarred by violence and ravaged by drug addiction. He served time at San Quentin and other prisons, and parole requirements kept him from leaving California for decades. One consequence of this is that while he came to prominence in the early fifties, he didn’t play New York as a leader until 1977. Nonetheless, his horn flowed with lyrical beauty and inventiveness, and he was a favorite of Contemporary Records founder Lester Koenig. Among the numerous recordings he made in the fifties, the best known is Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section, a 1957 date with Miles Davis’s sidemen Red Garland. Paul Chambers, and Philly Joe Jones. The album shows up often on desert island lists and the Penguin Guide gave it its royal crown.

However, like many modernists who’d already come to prominence by the late fifties, Pepper grappled with the powerful influence of John Coltrane and the advent modal jazz. Trane’s impact coincided with an especially unproductive time in Pepper’s life. Between 1961 and 1975, a period occupied by San Quentin, rehab at Synanon, and a late sixties stretch with the Buddy Rich Orchestra, he went virtually unrecorded. About the only example we have of the music he was making at the time is his 1964 appearance on the public television show, Jazz Casual. The series was hosted by Ralph J. Gleason at KQED in San Francisco. In conversation with Gleason, Pepper acknowledges that the music he was playing on Jazz Casual was what Gleason called a “radical departure” from the style for which he was known.

Pepper’s autobiography, Straight Life, doesn’t mention the Jazz Casual date, but it discusses this experimental period, and includes testimonials by his bassist Hersh Hamel and by the veteran drummer and L.A. jazz club proprietor Shelly Manne.

Hersh Hamel: “At that time, we decided to form a group. I was running around with a drummer, Bill Goodwin, who’s a great drummer, and we got Frank Strazzeri, myself, and Art… and we rehearsed and got some music together. Art had written some tunes in San Quentin which were very interesting, “D Section,” “The Trip,” “Groupin’,“ and I wrote a couple tunes, so we had a little library of original things. When Art first came out [of prison], he wasn’t using [heroin] much at all; we played a gig at Shelly’s Manne Hole and Art had a tremendous lot of fire.

“Art was very influenced by Coltrane at that time because he was in jail with some pretty radical players. Art heard those guys in Quentin and at first he didn’t like it so much, but after hearing them practice day after day, he started to pick up on what they were doing and to like it more and more. And then, when he came out, he was pretty well exploding musically. So much so that when we went into Shelly’s in 1964, Shelly Manne and some of the other guys criticized him terribly, ‘Oh no, that’s not the old Art.’

“And Art is so sensitive. When people start criticizing him he immediately starts bending…I think some of the harshness came from the fact that Art had spent a lot of time in jail. There was a lot of hostility, a lot of pent-up emotion, and when he played he was barkin’ boy! It was raw emotion and it was great. Incredible! If [only] we could have recorded [an album] at that time. Les [Koenig] recorded us on a few tunes but he didn’t like it.

“We went up to San Francisco at that time. I got some jobs for us and we worked at Don Mupo’s club in Oakland for two nights. We started Friday night; on Saturday night the last tune we played was “The Trip,” and the people were standing on top of the tables. I kid you not. The place was packed solid…people were standing on the tables, cheering, while we were playing. I’ve never seen anything like it; in jazz this very rarely happens. At that time, the level we were playing on was very, very good.”

Shelly Manne:“When Art came out of prison and did his first club date I didn’t like what I heard. Not because he wasn’t doing it well, but I didn’t feel it was an honest expression of the person I [knew] after listening to him for all those years. It’s OK to borrow from somebody like John Coltrane, but Art lost a lot of that lyrical quality that I love about him. When Art overblows his horn, the individual sound he has just disappears. I was sorry to see it, but now, more recently, I heard him reverting to himself. And that other stuff is absorbed into his playing and is expressed by his own identity, which makes it still an individual thing. But there was a period when I thought he was losing his way…That happens to a lot of players but they find that the best thing to do is to go play the way you feel because nobody can do it the way you feel, and if it’s good, it’s good.”

Art Pepper: “By 1964, when I got out fo San Quentin and started playing again, more and more I found myself sounding like Coltrane. Never copied any of his licks consciously, but from my ear and my feeling and my sense of music…I went into Shelly’s Manne Hole with a group, a lot of people liked what I did and thought I was playing modern, and a lot of others asked what happened to the old Art Pepper.

“When I got out of the joint the last time in ’66, I had no horns. I could only afford one horn, and I got a tenor because, I told myself, to make a living I had to play rock. But what I really wanted to do was play like Coltrane.

“In ’68 I got the job playing lead alto with Buddy Rich [in Las Vegas]…I was blowing Don Mensa’s alto in the motel room…jamming in front of the mirror, blowing the blues, really shouting, and all of a sudden I realized, ‘Wow, this is me! This is me!’ Then I realized that I had almost lost myself. Something had protected me for all these years, but Trane was so strong he’d almost destroyed me.

“That experience– it lasted about four years that I was influenced so much by John Coltrane– was a freeing experience. It enabled me to be more adventurous, to extend myself note-wise and emotionally. It enabled me to break through inhibitions that for a long time had kept me from growing and developing. But since the day I picked up the alto again, I’ve realized that if you don’t play yourself, you’re nothing. And since that day, I’ve been playing what I felt, what I felt, regardless of what those around me were playing or how they thought I should sound.”