I’ve had little but B.B. King in mind and on the home stereo since he entered hospice two weeks ago. The great bluesman has been a constant in my life for the better part of five decades, and while I’ve been profoundly touched by musicians across a wide range of styles, BB’s unique among them as a player who overwhelms me with emotion almost every time I hear him. Foremost among the rush of feelings I experience is gratitude for the man who wore the crown of King of the Blues with dignity and purpose throughout his long career. Or, perhaps in keeping with a person who embodied such majesty, it’s more fitting to say he wore it for a lifetime, as even his descriptions of a Mississippi childhood spent orphaned and farming are imbued with a sense of wonder and equanimity. “It was one of the happiest parts of my life,” he recalled in an interview with Stanley Dance in 1967. “I once tried to figure out how far I must have traveled in ten years of ploughing, six of them behind a mule. I never heard of a vacation until I left the plantation.”

One wonders if he ever took one? BB’s work ethic carried over into his career as a bandleader who maintained a grueling schedule over the course of 65 years, often playing more than three hundred one-nighters a year. But with his death on May 14 at his home in Las Vegas, the Beale Street Blues Boy has reached the end of the road. Riley B. King was 89.

Among the giants of American music, King impresses me as one of the few who never needed a second act, though he certainly benefited by a second audience. BB began his ascendancy in 1951 with his number one R&B hit, “Three O’Clock Blues,” and over the next dozen years released a steady stream of singles for Modern, RPM, and Kent Records. Modern packaged many of his 45’s for its LP imprints, Crown and United, and occasionally produced album-length sessions on the guitarist. King’s personal favorite was a 1960 date with blues piano legend Lloyd Glenn called My Kind of Blues. It is virtually the only session of BB’s that dispensed with horns, and it departed from his standard repertoire and new originals to feature the blues classics “Hold That Train, Conductor,” “Driftin’ Blues,” and the Roosevelt Sykes originals “Sunny Road,” and “Drivin’ Wheel.”

The majority of BB’s RPM sides featured tight horn arrangements by Maxwell Davis, an LA-based saxophonist who’s an unsung hero of post-WWII r&b. Davis’s arrangement of “Early in the Morning” is a great example of how he showcased King’s singing and guitar in dynamic interplay with horn sections and soloists. One would be hard pressed to contain a “Best of B.B. King” from this period with anything less than two dozen records, and while several of them charted as radio hits, BB’s popularity was driven mostly by personal appearances and a perfected celebration of the blues as cultural spectacle. Ron Levy, the Boston-born pianist who played with King between 1969 and 1976, said BB’s effect was “akin to a religious awakening, unbridled, passionate [and] earthy…[but] sharply honed…He was a master.”

King was intensely disciplined and focused as a musician and bandleader. Long after he was hailed as the most influential blues guitarist of all time, he continually worked at developing greater mastery of the Gibson ES’s he long personified as Lucille. In Levy’s lively memoir, Tales of a Road Dog, he says BB “was always studying, learning, and refining his guitar virtuosity, relentlessly searching for a new bend, lick, riff, or chord to add to his already potent arsenal.” More importantly, King grew as a figure who understood that success meant taking on the role of spokesman, teacher, and ambassador. In this regard, his heroes included the royals of jazz, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, and Nat King Cole, for there were no comparable models among blues players, and to this day, meaning for all time, no other bluesman will come close to attaining the stature of the King.

Nonetheless, even this soulful preacher of the blues saw his popularity among African Americans begin to decline in the sixties. “I fell between the cracks of fashion,” he said in his 1996 memoir, Blues All Around Me, and on at least one occasion he was booed. It was a first for the King, and it was devastating. “Never had been booed before. Didn’t know what it felt like till the boos hit me in the face. Coming from my own people– especially from young people– made it worse.” But serendipity was a career-long companion of King’s, and as one audience receded, another came to the fore. When whites began discovering the blues in the mid-sixties, King made the transition to new venues and demographics without compromising the spectacle or his role as its conjurer. Many other bluesmen and women made the leap too, but few had BB’s gift for maintaining the music’s ecstatic power and for making every club, arena, and student union feel as down home as the chitlin’ circuit.

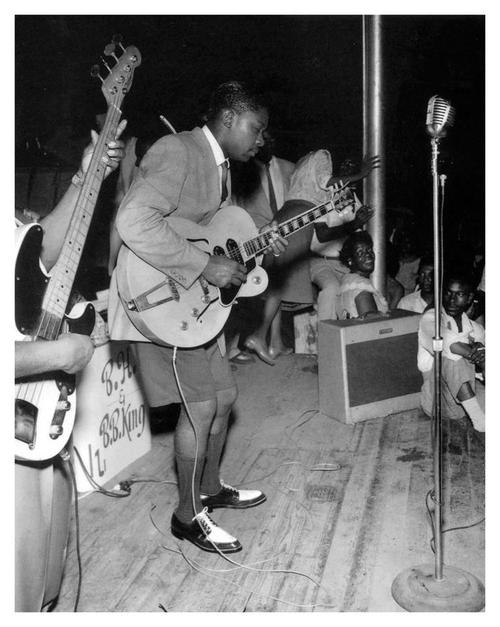

After signing with ABC in 1963 for $25,000, BB’s popularity grew with the release of live concert albums, and his biggest chart success, “The Thrill Is Gone,” which reached number fifteen on the Billboard Hot 100 pop chart and number three on the R&B. (It’s hard to believe today, but I actually got tired of hearing BB all over the radio in the summer of 1970.) Live at the Regal, Blues Is King, and Live and Well are virtually unequaled demonstrations of a bluesman working his magic before theater and nightclub audiences. For the generation of young whites then coming into contact with the blues, BB’s 1964 performance at Chicago’s Regal Theater was both a primer on what they’d been missing and a stunning eye opener on how enthralled a fan base could be. Few crescendos have been more communally acclaimed than BB at the Regal singing, “I gave you seven children, and now you want to give ’em back!!!” Click here to hear the classic “How Blue Can You Get.” (King is seen below in 1968 singing “That’s Wrong, Little Mama” before an especially responsive audience.)

King’s successes (Grammy awards; honorary doctorates; product endorsements; halls of fame; household name status; audiences with popes, presidents, monarchs and other heads of state) did nothing to diminish his compassion for people in need. His 1970 album, Live in Cook County Jail, signaled his new commitment to bringing the music into prisons. In 1971, he and defense attorney F. Lee Bailey founded FAIRR, the Foundation for the Advancement of Inmate Rehabilitation and Recreation. King’s advocacy played a role in Illinois’s decision to credit “time served” in the sentencing of convicts who’d often spent long periods in jail awaiting trial. He gave dozens of prison concerts over the years, and his 1990 recording Live at San Quentin, won the NEA’s National Medal of the Arts. His motive, he wrote in Blues All Around Me, “was never for money, but only the satisfaction of touching souls that needed to be touched. It didn’t matter that I’d never been in criminal trouble myself. I’d known men who’d gone to prison and understood how the circumstances of their lives led them there.”

Shakespeare taught us that monarchs often do better by their kingdom than their castle. King readily acknowledged that while he was a good financial provider for the fifteen children he fathered with numerous women, including two wives, he was largely absent from their lives. In Blues All Around Me, he said, “I have not been a good father…I was an absentee father. Sometimes I must seem foreign to my children.” He adds that most of his children are doing well, “while others struggle to find their place in the world.” One of the sad ironies of his prison work is that when he played a penitentiary in Florida in 1998, his daughter Donna was among the inmates. (BB is seen below performing “How Blue Can You Get” on Thanksgiving Day at Sing Sing.)

The first time I saw BB in person was at the Sugar Shack in Boston. I’ve forgotten exactly why, but for reasons having either to do with being underage or simply not having the cover charge, I never got closer than the lobby of the club. But even from that slight remove, hearing BB in person was all it took to turn me into a fan for life. The next time he came through town I caught the band in full view, and what a sight, seven tuxedoed gents playing an opening pair of instrumentals before the King entered to the punching riffs of “Every Day I Have the Blues.”

I saw him dozens of times thereafter, about fifty altogether, and was never less than awestruck. BB’s repertoire didn’t change much, so even blues-loving friends often asked why I kept going, but that’s like asking people why they go to church every week. There are just some eternal verities worth attending to ritually and continually. To anyone who asked if I recommended they see him, I answered that it should be regarded as their duty.

The only time I met BB for more than a handshake was when he played the UMass Fine Arts Center on December 7, 1999. When I was invited to his post-concert reception, I eagerly accepted and was treated to a private audience with the King for about fifteen minutes. BB was poised to sign autographs for dozens of fans who’d queued up to meet him just outside the door, but he showed no signs of impatience with my questions.

I asked him about the Phillip Morris Superband world tours he’d made in 1990 with Ray Charles and a band stocked with the jazz greats Harry “Sweets” Edison, Plas Johnson, Gene Harris, Kenny Burrell, Ray Brown, and Harold Jones. He still seemed excited by the memory, and said that hearing Burrell, who was his favorite jazz guitarist, was like hearing “a lecture from a great university professor every night.” King’s humility in discussing these and other jazz artists was confirmed several years later when I befriended the saxophonist Gary Smulyan. Gary’s baritone anchored the sax section on both of the Superband’s tours, and he said BB was amazingly gracious and respectful of the players, riding on the band bus and delighting in the company of musicians whom he admired. (Here’s BB with the Superband at the Apollo singing “When Love Came to Town,” “All Over Again,” and a medley of “Night Life” and “Please Send Me Someone to Love.”)

I also asked him about the big band recordings he’d made in 1959 of the Ellington standard, “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” and his session with Count Basie in which he sang “Everyday I Have the Blues.” The Memphis Slim blues original was already BB’s show opener (actually, it was Lowell Fulson’s version, just as it had been Fulson’s recording of “Three O’Clock Blues,” that were King’s inspirations), but for the session with Basie he sang the classic Ernie Wilkins arrangement that the Count and Joe Williams had made famous in 1956.

BB told me he’d hardly ever been asked about those sessions, and recalled being nervous at the prospect of recording with Basie, whom he’d first heard at the Jones Night Spot in Indianola, Mississippi around 1939. In Blues All Around Me, he recalled Basie as “a round-faced man [whose] music was modern and swinging and beautifully loud, as bluesy as anything I’d heard in the Delta. I believe I listened harder that night than anyone in the history of listening.”

King was born in Ita Bena, MS, a rural Delta crossroads, on September 16, 1925, but he named the nearby Indianola as his birthplace. It was there as a young teen where he discovered his passion for music and the model for what he would later project from stages around the world. “I’m a fan first,” he said in Blues All Around Me. “As a kid hanging around Church Street, the presentation of music was so powerful, I couldn’t help but jump for joy. I had discovered art, or truth, or whatever you want to call it; I had seen a light I’d follow forever.”

Here’s BB on his birthday, probably in 1968, introducing his blues idol T-Bone Walker. King’s humility is evident as he says what a wonderful birthday gift it was to share the stage with “this wonderful gentleman.” Another of BB’s favorites, the aforementioned Lloyd Glenn, who toured with T-Bone, is at the piano.

The blues light is now dimmed. It’s been flickering for decades, but King’s high profile helped assure that the world remained aware of the blues as the creation of blacks and the bedrock of African American music. While he long lamented the music’s decline in popularity among African Americans, he personally encouraged many of the whites who idolized him and sought his imprimatur. (Rolling Stone makes it plain in a memorial feature headlined 10 Legendary Acts That Wouldn’t Exist Without B.B. King. The names include the Butterfield Blues Band, Jimi Hendrix, Cream, Led Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers, Santana, Johnny Winter, Fleetwood Mac, ZZ Top, Robert Cray, and Jimmie and Stevie Ray Vaughan.) White musicians have increasingly been the face of the music since the sixties, but as long as he was on the road, BB was its unrivaled standard bearer. Maybe that’s what kept him out there so long. Alas, we’ve now lost our King.

Documentary footage abounds on BB. Here’s a great example of his easy and heartfelt rapport with an audience of hippies near Albuquerque in 1970. It opens with the requisite “How Blue Can You Get,” followed by “Just a Little Love” and a killer instrumental brimming with the kind of lyricism that made King’s guitar playing such a deeply emotional experience. The camera angles in this production capture much of the nuance that made BB the undisputed King of the Blues.