There’s a memorable scene in the documentary A Great Day in Harlem between Benny Golson and Horace Silver. Golson is recalling the many nights in which a good tune has come to him in a dream, but rather than get up and jot it down, he’s gone back to sleep confident he’ll remember it in the morning. Once he awakes, however, he finds it’s gone without a trace. Having finally learned his lesson, he wakes up one night with a magnum opus in mind, goes downstairs to his studio and writes it out, and then goes back to bed. Benny continues, “When I got up…and went down and started playing it, I said to myself, ‘Wait a minute. This sounds familiar.’ You know what it was? It was the verse to ‘Stardust’!” Watch the scene for yourself on this part of A Great Day in Harlem, where it begins at 8:30.

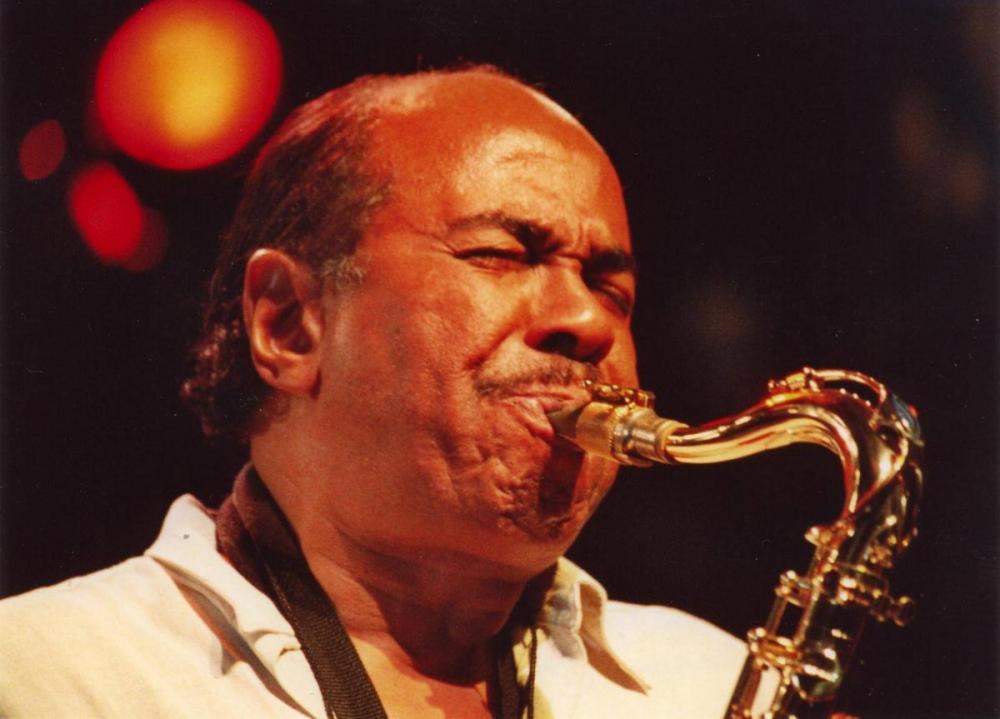

Today is Benny Golson’s 83rd birthday. For over 60 years, the Philadelphia native has been wide awake as dozens of tunes have come to him. Golson standards include “Stablemates,” “Blues March,” “Killer Joe,” “Are You Real,” “Five Spot After Dark,” and “Whisper Not.” His best-known composition, “I Remember Clifford,” is one of the most performed jazz originals with over 300 recorded versions. Here’s an appreciation of his memorial for Clifford Brown at Jazz Standards.com.

Golson was a personal friend of Brownie’s, and they were colleagues in the Tadd Dameron Orchestra in 1953. The following year, Brown and Max Roach established their renowned quintet, and later commissioned the Golson original, “Step Lightly,” which they recorded in February 1956 with Sonny Rollins. The previous year, both Herb Pomeroy, the Boston-based trumpeter, and Miles Davis made recordings of “Stablemates.” These assignments helped put Golson on the map as a composer.

On June 26, 1956, Clifford Brown was killed in a car crash on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. Here you’ll find Golson’s vivid recollection of hearing the news of the 25-year-old trumpeter’s tragic death when he was backstage at the Apollo Theater working with Dizzy Gillespie. When “I Remember Clifford” was premiered on March 24, 1957 by the 18-year-old trumpeter Lee Morgan, Golson was quoted in the liner notes of the Blue Note album entitled, Lee Morgan, Volume 3. “I worked with this melody for three weeks, trying to get a melody that would be reminiscent of [Clifford] and the way he played…I was very moody while composing this song because with each note I wrote, I realized that it was to someone who had gone—my friend forever.”

Golson describes himself as a “musical bigamist” who’s equally loyal to his skills as a writer and player. But his early success as a composer led to a restlessness to establish himself more fully as a tenor saxophonist, which he developed a highly individual approach to through the influence of Coleman Hawkins, Don Byas, and Lucky Thompson. By the mid-50’s, he’d logged several years playing journeyman tenor with the swing and jump blues bands of Bullmoose Jackson, Lionel Hampton, and Earl Bostic, and as he told Mel Martin in this extensive interview, he was eager for work playing modern jazz. A recommendation from Quincy Jones landed him the job with Dizzy’s big band in 1956, and two years later he joined Art Blakey in one of the most renowned editions of the Jazz Messengers, the outfit with Lee Morgan, bassist Jymie Merritt, and pianist Bobby Timmons, a group I think of as a veritable model of Philly Soul. The band’s landmark recording, Moanin’, was Golson’s only date with the Messengers, but his robust tenor and original compositions, “Along Came Betty,” “Are You Real,” and “Blues March,” make it one of the most popular and essential from Blakey’s voluminous discography.

The Jazz Messengers served as a prototype for The Jazztet, the sextet that Golson established with Art Farmer in 1959. Many consider Farmer’s 1960 performance of “I Remember Clifford” to be definitive, his lyrical style as a trumpeter the perfect complement to Golson’s beautifully-crafted tunes and arrangements. Not surprisingly, Golson’s songs have attracted lyricists, including Jon Hendricks who wrote words for “I Remember Clifford.” Dinah Washington, who’d recorded with Brownie in 1954, made the first lyricized version in 1958, and Sarah Vaughan and Helen Merrill, who’d recorded with Brownie, followed suit. But instrumental versions far outnumber vocal, and that’s apparently what Benny prefers.

In 2009, Golson told John McDonough for a DownBeat cover story that he generally disapproves of people writing lyrics to jazz compositions. “I usually hate those attempts to take a jazz tune and put a lyric to it. Worse is putting words to improvisations. It’s not my cup of tea.” Nor is it mine, as I often find that lyrics superimposed on jazz originals have a trivializing impact on the overall integrity of the composition. Moreover, they’re hard to shake once they’re in your head. Think “Goodbye Porkpie Hat.” But there are exceptions (“Moody’s Mood for Love” and “Parker’s Mood” by Eddie Jefferson, and Jon Hendricks’s “In Walked Bud,” spring to mind), and as Golson acknowledges, many are well-intentioned. “I guess they think they’re doing you an honor when they put words to your songs and you should be happy about it,” he told McDonough. “But I have to say, ‘I’m sorry’.”