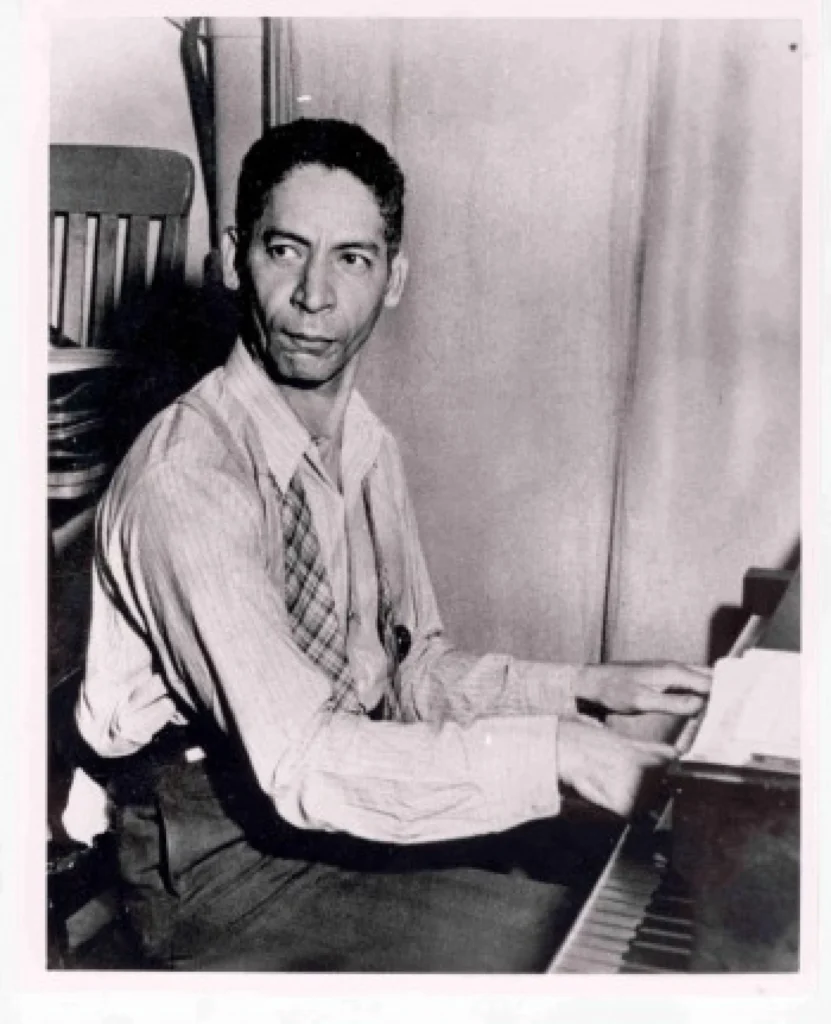

Jelly Roll Morton immortalized the most mythical of New Orleans jazz pioneers in his composition, “I Thought i Heard Buddy Bolden Say.” He recorded it twice in 1939, first for RCA Bluebird with a band that included New Orleanians Sidney Bechet, Albert Nicholas, Wellman Braud, and Zutty Singleton. Four months later, on December 16, 1939, he recorded the tune as “Buddy Bolden’s Blues” on a solo session for General Records. It was later released in an album by Commodore.

If you’ve got an ear for how the sacred and secular sometimes merge in the blues, consider the testimony of Bud Scott, the guitarist and banjo player who shouted “Oh, play that thing!” on King Oliver’s classic recording of “Dippermouth Blues” featuring Louis Armstrong.

Scott was born in NOLA in 1890, and despite his youth, he knew what it was like to play opposite experienced Bolden’s powerful appeal and aura. Scott was 14 when he began playing with John Robichaux, whose band engaged in contests with “King” Bolden. Scott says Bolden got so “hot-headed” after being bested on one occasion by Robichaux’s band featuring trumpeter Manuel Perez that next time out he “stripped” Lincoln Park of Robichaux’s fans by “slipping his horn through the knothole in the fence and calling the children home” to Bolden’s perch at Johnson Park. (Jon Cleary invoked Bolden at the Iron Horse in Northampton on Monday night/Lundi Gras with the “calling his children home” words. New Orleans musicians are as ever steeped in myth.)

Then Scott got down to declaring the primary influence on Bolden’s innovation. “Each Sunday, Bolden went to church and that’s where he got his idea of jazz music. They would keep perfect rhythm there by clapping their hands…Bolden was still a great man for the blues– no two questions about that…He was a great man for what we call “dirt music.”

Morton’s blues for Bolden is dirty alright, and in the voice of “Frankie Dusen” he gets quite dramatic, but this commercial release only hints at the explicit language he used when he recalled his New Orleans heyday with Alan Lomax at the Library of Congress in 1938. Still, his solo version is both a masterpiece of blues singing and keyboard elaboration, and an extraordinary combination of the ribald and the elegiac. Click here for the solo version, and here for Morton’s Bluebird original featuring Sidney Bechet on soprano saxophone.