The news last week that Bob Dylan was being awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature signaled another level of recognition, maybe the ultimate, in the ongoing acceptance of rock’n’roll as an art form. Between the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, the conferring of knighthoods and the Presidential Medal of Freedom on rock icons, and the presence of rock in the groves of academe, the music seems as secure as could be.

But the word on Dylan had hardly broken before social media began swirling with the names of those whom others felt were equally or more deserving of the honor, among them Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Smokey Robinson, Paul McCartney, and Richard Thompson. My guess is that the Nobel Committee won’t make a habit of naming persons known primarily as songwriters over novelists and poets, but I would argue that if the discussion returns to lyrical luminaries of the music world, Chuck Berry should be among those short-listed.

As it happens, Berry was honored four years ago by P.E.N. New England with its Songs of Literary Excellence Award. He and Leonard Cohen were the first recipients of the award, and for the occasion, the Pulitzer Prize winning poet Paul Muldoon said, “Take what we used to refer to as a boy and a girl and set them down in an automobile, front seat or back, and you have the essence of rock’n’roll. That realization was Chuck Berry’s great gift to our culture. He helped people in the U.S. make sense of themselves. He also helped people like me in Ireland who knew in our hearts we belonged in the U.S. make sense of ourselves. What a thrill to honor one of the inventors of a genre that has quietly outlived so many of its loudest critics.”

Berry was also cited by George W. Bush a few weeks ago at the opening ceremonies of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. When the former president took the podium in Washington, D.C., he named Berry as a personal favorite and the foremost example of the pervasiveness of black culture in the nation.

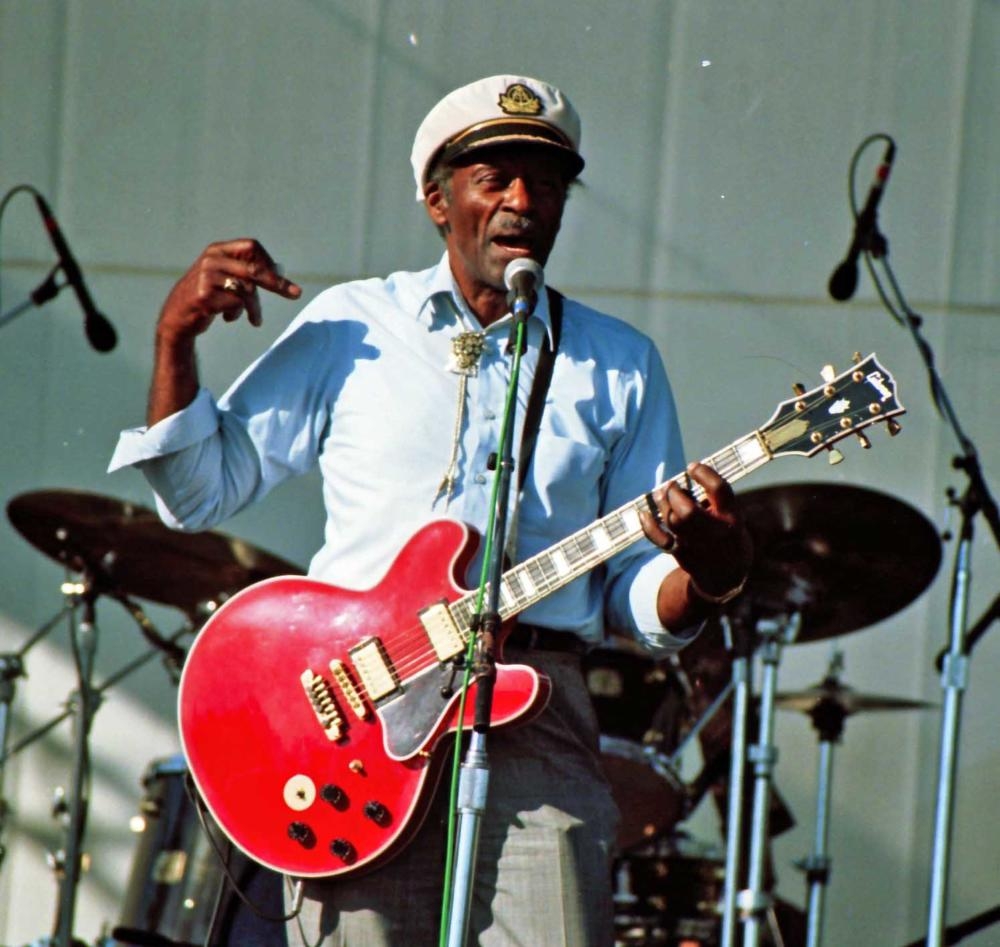

Today is Chuck Berry’s 90th birthday. In celebration, I’ve listened to his classic Chess singles and watched the Taylor Hackford documentary about Berry, Hail! Hail! Rock’n’Roll! I also took another look at Chuck’s appearance in the documentary Jazz On A Summer’s Day. Bert Stern’s classic film of the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival takes little notice of the rain that fell on the festival that weekend, but if there’s a storm cloud on the horizon in this otherwise sunny documentary, it’s Berry, who enthralled the crowd but puzzled his accompanists in the hastily assembled Newport Blues Band. One of the most indelible images I carry from the film is the bemused look on the faces of jazz greats Jo Jones, Buck Clayton, and Jack Teagarden as they watch him do the duck walk on “Sweet Little Sixteen.”

Newport endured riots in 1960 and ‘71, but even though the audience kept its frenzy in check for Chuck, booking him marked a line of demarcation between a festival devoted exclusively to jazz and what its founder George Wein describes as a “capitulation to the pressures of a rock-and-roll generation.”

Wein reports that it was John Hammond who produced the Saturday night blues showcase that included Berry. Hammond had presented a panoply of jazz, blues, gospel and boogie woogie at the groundbreaking Spirituals to Swing concert at Carnegie Hall in 1939. But the guitar slinger from St. Louis was another matter. “I was dead set against Chuck Berry,” Wein recalled in his memoir My Life With Others. “Rock and roll…did not belong on the Newport Festival…When he went into his duck walk, I literally cringed. I could almost feel the [critics’] knives…Needless to say, the crowd loved it… [And] the grand irony is that putting [him] on at Newport was a daring move that led to similar presentations all over the world. So I get credit for being a visionary…but John Hammond deserves the credit. Incidentally, I’ve grown to like Chuck Berry’s music.”

Well, who hasn’t? Clarinetist Rudy Rutherford surely got it. Big Tea and Papa Jo would have recognized Berry’s roots in the blues, and the spirited buck and wing that a poplin-suited gent cuts while Chuck sings his ode to the girl in “tight dress and lipstick” underscores how much his music was rooted in the same vernacular as jazz. But in this case, one man’s vision may be another’s slippery slope, and the apparently irreversible trend we’ve seen in de-emphasizing jazz at jazz fests began at Newport on July 6, 1958. Newport went on to feature major rock acts in the 1960s and early ‘70s, but the storming of the gates in 1971 shut the festival down and sent it looking for a new home. A pleasing reversal of Wein’s “capitulation” is that the festival he re-established at Fort Adams State Park in Newport in the 1980s is a jazz purist’s delight, and a big draw. It’s the Newport Folk Festival that now hosts rock’n’roll.

Charles Edward Berry was born in St. Louis on October 18, 1926. His brother Paul remembers him in youth as “a deep thinker who loved to hear and play the blues.” On his 1973 album Bio, the title song recalled his mid-‘50s sojourn to Chicago, with Berry singing, “Just to hear Muddy Waters play…I asked him what I could do to make it, and it was he who showed me the way.” What Muddy showed him was the way to Chess Records, a magnanimous gesture that Deep Blues author Robert Palmer called “cutting his own throat.” Berry’s success, and that of another Muddy protégé, Bo Diddley, quickly minimized the value of the modest success that Waters and other Chicago bluesmen enjoyed in the ‘50s. Once “Maybelline” began climbing the charts, Leonard and Phil Chess knew they’d finally struck a motherlode, and while they continued to record the bluesmen who’d put them in business, mining Top 40 gold became the focus of their efforts.

In his classic single “Rock and Roll Music,” Berry famously said he “had no kick against modern jazz.” Eric Clapton credits him with creating a “beautiful hybrid” that drew on jazz, calypso, country, and blues. Keith Richards says Berry’s combined skill at songwriting, singing and guitar playing put music “back in the troubadour tradition.” In Berry’s case, however, traditional themes of chivalry and courtly love were superseded by teenage preoccupations with school, cars and crushes, while the adult trickster in Berry subtly laid down boasts about black male sexuality in tunes like “Brown-Eyed Handsome Man” and “Too Much Monkey Business.” Neither, by the way, made the hit parade.

In Hackford’s film, Roy Orbison praises Berry’s lyrics for the way they “roll off the tongue…stab and cut… and lay there with the drum,” while in footage from a decade earlier, John Lennon says he loves “the tremendous meter of his lyricism.” Lennon also proposed the name “Chuck Berry” as a synonym for rock’n’roll. Jerry Lee Lewis, who feuded nastily with Berry for top-billing early in his career, concedes that he’s the true king, “The Hank Williams of rock’n’roll.” As for his guitar playing, Clapton says, “There’s not really any other way to play rock’n’roll guitar other than the way Chuck Berry plays it. He’s really laid down the law.” Richards contends that Berry “adapted” his guitar style in emulation of pianist Johnny Johnson, who’d given Berry his start when he sat in with Johnson’s trio at the Cosmo Club in St. Louis in 1952, then gladly handed over the reins of the group to Berry, whom he calls a “go-getter.”

Richards signed on as music director of Hail! Hail! Rock’n’Roll after he’d inducted Berry into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 1986, its inaugural year. Richards said, “It’s very difficult for me to talk about Chuck Berry ’cause I’ve lifted every lick he ever played — this is the gentleman who started it all!” Notwithstanding the flare-ups that Hackford captures between them, Richards carried the project through to completion, though in his memoir, he says Berry “pushed me hard–you can see it in the film. It’s very difficult for me to allow myself to be bullied…but I owed it to Chuck to bite the bullet when he was at his most provocative.” In 2005, Richards sent a fax to Berry that read, “Despite our ups and downs, I love you so! Your work is so precious and beautifully timeless. I’m still in awe.”

In the movie, Berry is refreshingly modest about his vaunted role as an inventor. “Making it simple,” is how he describes the process of assimilating his influences. “You can call it my music, but there’s nothing new under the sun.” Who were those influences? He ticked off several near the end of his appearance on The Tonight Show in 1987, beginning with Louis Jordan, who was paramount, along with Tympany Five guitarist Carl Hogan and Charlie Christian of the Benny Goodman Sextet. He also cited the singing of Nat King Cole, and concludes by saying, “the soul of Muddy Waters. Oh, I had it all mixed up.”

He might have mentioned the great bluesman T-Bone Walker, country legends Bob Wills and Bill Monroe, and the gospel singer and guitarist Sister Rosetta Tharpe. In Gayle Ward’s 2007 biography of Tharpe, Shout Sister Shout! Ira Tucker of the Dixie Hummingbirds credits her with introducing “the duck thing.” But this was a friendly, informal exchange with Johnny Carson, not a musicological cross-examination. Nonetheless, Berry adds an interesting detail about how Chess sped up the original 45 rpm of “Maybelline” to make him sound younger than his 29 years, and says that it led to a dispute with Richards in Hail! Hail! Keith wanted a carbon copy of the original.

October 18 is also the birthday of Wynton Marsalis. In 1998, when I asked the trumpeter why he didn’t think rock’n’roll should be celebrated, he said, “Because it’s like…McDonald’s,” then added, “One thing it did do, it relaxed a lot of the sexual repression, but who knows if that wouldn’t have happened anyway. It also destroyed the adult culture of the world, because it became increasingly concerned with getting that exploitable income from teenagers and young adults, so then the aesthetic objectives of the American popular song didn’t carry over into rock and roll.”

In recent years, Wynton has collaborated with Eric Clapton and Willie Nelson. Is this a sign of maturity, or a ploy to pay the rent at Lincoln Center? I’ll go with the former. I came to a personal rapprochement between my measured appreciation for rock and my passion for jazz years ago, though I remain wary of rock’s omnivorous impulse to devour everything it finds pleasing, and the star-making machinery that goes with it. But I agree with Marsalis that it’s had a devastating impact on our appreciation of the Great American Songbook, which today lives almost exclusively in the repertoires of jazz musicians and cabaret singers. It’s rare indeed to meet anyone born after World War II who knows the songbook or relates to it emotionally.

Still, it’s Chuck playing one of the old standards that Hackford chose to conclude the documentary. In a quiet moment backstage with Johnny Johnson, Berry strums the chords to “A Cottage for Sale,” an elegy for lost love that his fellow Missourian Willard Robison composed in 1929. Leave it to the “deep thinker” Berry, to know better than most that it often takes more than three chord rock to express what Wynton calls the “aesthetic objectives,” and what the rest of us know as the longing in our hearts.

The inevitability of a figure like Berry emerging in the 1950’s was lost on many cultural arbiters of the time. Berry respected youth’s own truth, and his sly brilliance as a lyricist and the hearty self-affirmation that drives his music brought these core elements of African American culture into the mainstream and served as a prototype for rock songwriting. Bob Dylan, the Beatles, the Stones, Randy Newman, Paul Simon and others knew from and drew from Tin Pan Alley, but Berry’s ability to lyricize and express so many layers of the personal and social in the lives of black and white Americans was the key to opening this new chapter in the nation’s music.

P.S. Here’s Chuck in Toronto in 1969 performing the Muddy Waters classic, “Hoochie Coochie Man.” I saw the ever youthful, 83-year-old bluesman Bobby Rush on October 12 in Woonsocket, Rhode Island, and was curious to hear him make the claim that Willie Dixon approached him with the song in 1954. Bobby was a 21-year-old at the time and felt the tune was too much of an “old man’s song,” so he declined. Muddy was 41, but none too old to make the boastful tune his signature song. Listening to the 43-year-old Berry sing it here, I think Rush was on to something. It’s not that “Hoochie Coochie” is an old man’s song, it’s just that it takes a mature man who knows the real power of his appeal to put it over.