As noted here a few weeks ago, Clark Terry has been hospitalized this fall, and his right leg was amputated on Wednesday. Clark’s wife Gwen reported this morning that he’s “making a good recovery, is cheerful and eating solid food again.” She asked his friends and fans to “pray with strong faith.”

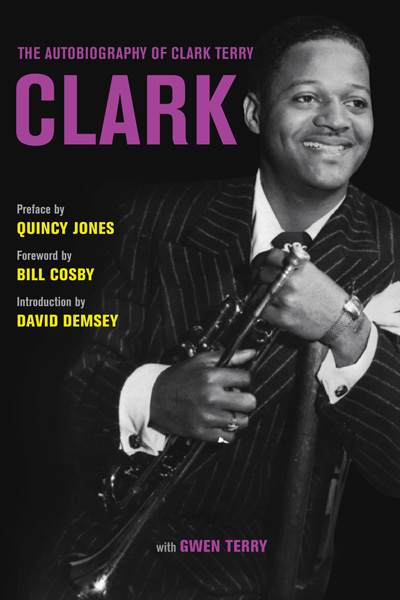

In the midst of this serious news, I’m happy to say that I’ve gotten to know and like Clark even better through his memoir, Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry. Published by the University of California Press, this 300-page account of Terry’s long and accomplished life is one of the best I’ve ever read in the distinguished genre of jazz autobiography. From an opening sentence in which we’re introduced to his boyhood friend Shitty and soon read of Clark’s youthful discovery that “you can’t eat beans and keep it a secret,” this tale is full of laughs. Where Bill Cosby created a brilliant monologue about how he became disabused of the idea that he would someday make a good jazz drummer, conversely, I’m sure Clark would have flourished as a comic. His story is rich with sights, sounds and smells, especially the latter. Might amazing olfactories go hand in hand with a brass player’s embouchure? Clark’s memory for everything from funky to fragrant is remarkable.

He’s also refreshingly candid about himself, his family and colleagues, and poignant about the realities of life in the era of segregation. Terry’s not afraid to say when he’s feeling afraid or vulnerable or mad, or how he often wished that his father, who railed against jazz and put Clark out of the family home in St. Louis for good at age 12, would have come around to recognize his accomplishments, among them a 2010 Grammy for Lifetime Achievement.

After his tenures with Count Basie and Duke Ellington, Terry became the first African-American to be hired as a staff musician at NBC, and he spent ten years on the Tonight Show band. But before he arrived at this level of achievement, he paid the kind of dues that were de rigueur for black musicians on the road, the daily struggle to secure basics like food (cooking on hot plates and upturned irons) and accommodations (lights on/lights off disputes with Basie in stiflingly hot attics; all-night rides and early morning check-ins for day rates at “sleazebag motels”); trying to sleep on Ida Cox’s rickety bus while touring the minstrel circuit, or to grab a corner of what was left of the seat he shared with Mr. Five-by-Five, Jimmy Rushing, when he joined Basie. His telling of the demise of Basie’s big band of the late 40’s offers new revelations about the devastating impact of the Count’s gambling habit, and his description of how Duke cajoled him into leaving Basie is as telling as anything you’ll ever read about this aspect of the “Ellington effect.”

I gained a deeper understanding for how much jazz meant to black musicians of Clark’s generation in reading of how he turned to the promise of its inherent dignity whenever he was faced with racism. “But on the inside I was more determined than ever to get respect from jazz,” is a frequent refrain in this inspiring narrative, one infused with the generosity of spirit and self-respect that have been hallmarks of Clark Terry’s music, and his extensive work as an educator-clinician, for over 65 years.

Here’s more information on Clark: The Autobiography of Clark Terry.