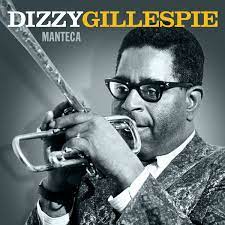

On Friday, a listener noticing that Dizzy Gillespie’s 95th birthday anniversary is today, asked where he could find a copy of “I’ll Never Go Back to Georgia.” When I told him that that’s the vocal refrain Gillespie created off the bass line that opens Manteca, not a separate tune, he said, “But it could have been.” How true, and Dizzy probably would have scored a second hit behind “Manteca” had he recorded a vocal follow-up. The song’s 2/4 rhythm is so infectious, it doesn’t need much more than the tongue-in-cheek warning about the perils of traveling to segregated Georgia to make it complete.

The first version I know of with the vocal is here on Dizzy Gillespie at Newport, which was recorded on July 6, 1957, about six months after Gillespie’s big band played an engagement in Atlanta. The band had already enjoyed the good vibes of a 1956 State Department tour of the Middle East with concerts in Lebanon, Syria, Pakistan, and Iran, and upon its return Dizzy was poised to go to Georgia.

In his memoir, To Be or Not to Bop, Gillespie writes, “[We] really scored socially in Atlanta, because this was a mixed band with a black leader playing in Georgia where whites were still struggling to hold on to segregation. One of the reasons we’d been sent around the world was to offset reports of racial prejudice in the United States, so I figured now we had a chance to give the doctor some medicine…We opened at the black-owned Waluhaje…and a lot of whites there wanted to come to see us and they did, with no segregation.”

But as trombonist Melba Liston remembers, “We were getting ready to leave Atlanta, and Dizzy was doing some funny antics at the airport. The band was really a New York band, right, all mixed. And he did something that made the police come by…So the cop came over and approached Dizzy, ‘Hey, what’s your name? Where you from?’ And he said, ‘I’m from Cheraw, South Carolina [his birthplace].’ The funniest thing was that Dizzy knew what the situation was, so he figured that would be an appropriate answer. The guys in the band saw what was happening and retreated from that area because they didn’t want to be a part of that. They said, ‘I’m ‘a see y’all, heah!’ Nobody knew Dizzy that night.”

Here’s a brilliant performance of “Manteca” that Dizzy made in Denmark in 1970 with the Clarke-Boland Big Band. That’s Ellington alum Jimmy Woode on bass; bebop innovator/MJQ co-founder Kenny Clarke playing cowbell and drums; and London legend Ronnie Scott on tenor saxophone.

Manteca, of course, is a good deal more than a riff against Jim Crow. When composed in 1947, it marked a watershed in the Afro-Cuban fusion that Dizzy and percussionist Chano Pozo brought about in modern music. “Chano had already figured out what the bass was gonna do,” Gillespie recalled. “He had that riff…But Chano wasn’t too hip about American music. If I’d let it go like he wanted it, it would’ve been strictly Afro-Cuban, all the way. It wouldn’t have had a bridge.” So Dizzy composed the tune’s famous bridge, a double-length16-bar span that owed part of its originality to Thelonious Monk.

“I learned a lot from Monk,” Gillespie wrote. “It’s strange with Monk. Our influence of each other’s music is so closely related that Monk doesn’t actually know what I showed him. But I do know some of the things he showed me, like the minor-sixth chord with a sixth in the bass. It’s demonstrated in some of my music like…the bridge to ‘Manteca’.”

Dizzy shared the composer credit for “Manteca,” which he called his “largest selling” record, with Pozo and Walter Fuller. “Anytime you hear something that Chano and I wrote…I didn’t just gorilla myself in it, I contributed. You see, when I use these guys from other cultures, I always try to understand their music…and I try to add something…The role of Walter Fuller in structuring, arranging, and orchestrating ‘Manteca,’ should not be overlooked, and he is properly listed as co-composer.”

Al McKibbon played bass with Gillespie beginning in 1947. He said the trumpeter “was kind of a revolutionary to me. He knew where it all came from, you know, African and Afro-Cuban…So when he got Chano Pozo in the band, that just killed me because I was always intrigued with drums, and to hear a drum played by hand was new to me. I’m from the Midwest, and here’s this guy beating a [conga] with his hand and telling a story. And Dizzy could see him in the band, but I couldn’t…Hell man, to me Count Basie’s rhythm section was it! So anyway, Dizzy was always that farsighted, that he could see Chano Pozo playing in his band…And look what’s come of it.”

Bringing it all back home, here’s Gillespie in Havana in 1985 playing a wonderfully celebratory “Manteca” with the young Arturo Sandoval on trumpet, John Lee on bass, and Walter Davis, Jr. among the pianists. Give me some skin!

Today is also the 100th birthday anniversary of Don Byas. The tenor saxophonist was born in Muskogee, Oklahoma on October 21, 1912, and died in Amsterdam in 1972. His career highlights include tenure with Gillespie in what’s widely considered the first bebop band, the quintet Dizzy co-led with Oscar Pettiford at the Onyx Club on 52nd Street in 1943. Three years later, Byas was with Dizzy on the trumpeter’s classic recording of A Night in Tunisia, a Gillespie original that was the harbinger of things to come. Apropos Al McKibbon, Dizzy recalled, “I wrote ‘A Night in Tunisia,’ where the bass player’s saying ‘de-de-de, doom doom, de-de-de, doom doom,’ instead of saying ‘doom doom doom doom.’ And the rhythm [section] played sort of a Latin beat behind that, and it worked out very well. Later, from that came ‘Manteca,’ which was really a mixture of Afro-Cuban and jazz, and that was the first definitive breakaway from the old beat.”