Duke Ellington’s first appearance at what was then called The New Orleans Jazz Festival and Louisiana Heritage Fair took place in 1970. It was the third annual jazz festival in New Orleans, but the first that George Wein produced under the Jazz and Heritage banner, and for the occasion Ellington was commissioned to write a new work entitled, The New Orleans Suite. Based on tapes of the concert that have surfaced in recent years, the suite’s opener, “Blues for New Orleans,” was the only movement that Duke performed at the festival. Ellington was famous for completing new works only minutes before deadline, but it would seem that most of the suite must have been ready at the time of the festival appearance on April 25 since its recording for Atlantic Records was completed only 18 days later on May 13.

Whatever the case, Wein’s introduction of Duke included the news that the festival would be returning the following year despite a loss of $40,000 in its inaugural presentation under his stewardship. (45 years later, the fest is thriving, but it’s content has changed considerably from Wein’s original conception of a weekend devoted to music from Louisiana.) Highlights from the Ellington concert include a Johnny Hodges mini-set of “Blues for New Orleans,” “Passion Flower,” and “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be;” a showcase for saxophonists Paul Gonsalves, Russell Procope, and Harold Ashby called “In Triplicate;” and Wild Bill Davis playing his famous arrangement for Count Basie of “April in Paris.” Duke credits the original “One more once/One more time” orchestration for “establishing a majestic way of monumental cool.”

Davis, a pioneering Hammond organist who came to prominence working with Louis Jordan’s Tympany Five in the early fifties, was a late arrival to the Ellington fold. On the rare occasions when Duke took a break from the road in the mid-sixties, Hodges fronted a combo in Atlantic City that included Will Bill, and they were co-billed on several RCA Victor albums. Davis is prominent on “Blues for New Orleans,” and he was with the orchestra on several occasions when I saw Duke in the early seventies.

At Jazz & Heritage, Duke hailed the orchestra as “Buddy Bolden’s second line.” Bolden was the New Orleans trumpeter whom legend regards as the most pivotal figure in the transition from ragtime to what later came to be called jazz, but his institutionalization for “acute alcoholic psychosis” in 1907 resulted in his near total absence from the historical and musical record. Officially, about all that exists on Bolden are records from the New Orleans City Directory and the Insane Asylum of Louisiana, but a photo of the trumpeter with his six-piece band and the published recollections of Jelly Roll Morton and Sidney Bechet give considerable support to Bolden’s stature as what Morton called “The blowingest man…since Gabriel.”

A “second line” of New Orleanians provided Ellington with an early and essential stylistic foundation beginning in the twenties. Barney Bigard was the band’s clarinet soloist for twenty years, and Wellman Braud, its first important bassist, propelled the band for a decade. Trumpeter Bubber Miley was a South Carolina native, but his main influence in developing the growling, “wah wah” brass style that became a signature element in Ellington’s tonal palette was New Orleans legend, King Oliver. And Bechet, who’d dated Hodges’s older sister when the great reedman was playing in Boston around 1920, toured with Ellington during the band’s summer sojourns in New England in the mid-twenties. He never recorded with Duke, but Ellington praised him as a player whose music was “all soul.” Credit New Orleans jazz, its origins and its legacy, with playing a vital and ongoing role in the imagination of Edward Kennedy Ellington.

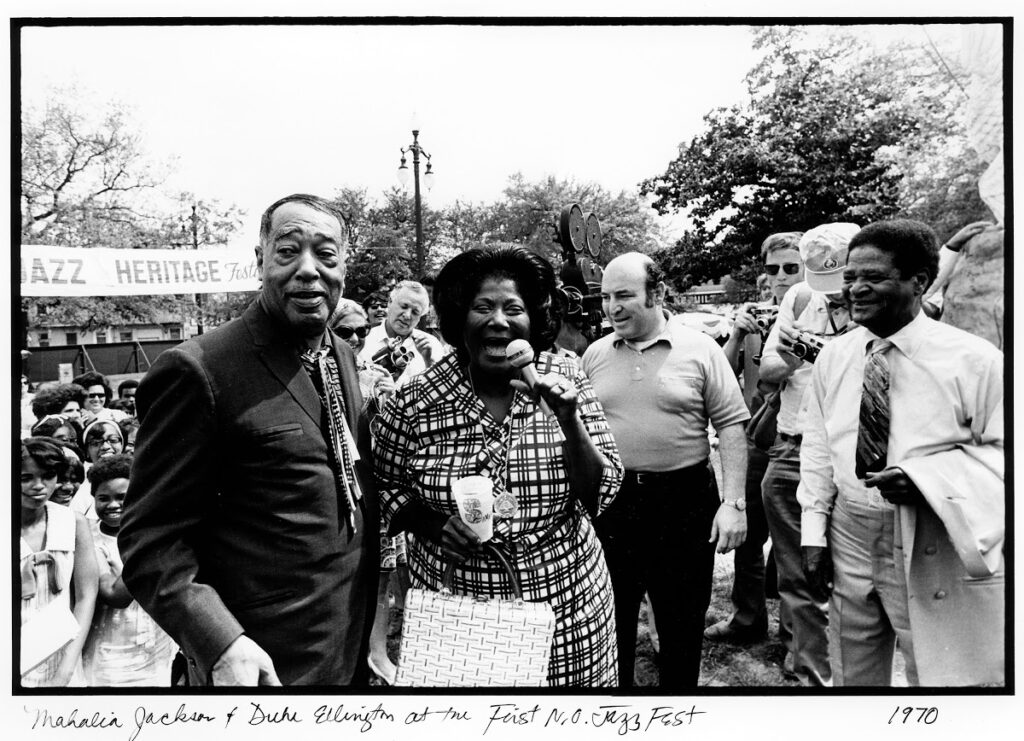

The New Orleans Suite was one of the most fully-realized of Ellington’s latter-day works, offering portraits of Bechet, Braud, Louis Armstrong, and Mahalia Jackson, and evocative pieces like “Bourbon Street Jingling Jollies” and “Thanks for the Beautiful Land on the Delta.” While its themes were historical, the music was right in step with jazz of the early seventies, and it won the Grammy for Best Jazz Performance by a Big Band in 1971. Alas, it was the last recording to feature Hodges. He died on May 11, 1970, and was reputedly poised to play soprano saxophone for the first time in almost forty years on the “Portrait of Sidney Bechet.”

There’s an important backstory involving Wein and Ellington in the earliest attempts at presenting a jazz fest in New Orleans, a city where segregation remained in effect throughout most of the sixties. Among the Jim Crow customs still in force were ones that permitted blacks and whites to be in the same place only out-of-doors, not in an indoor facility; and black and white groups could appear in succession, but not together, on the same stage. Crescent City officials first approached Wein in 1962, but when the impresario met with them in a private dining room at the Royal Orleans Hotel, he made it clear that his fest would include integrated ensembles, and that Duke Ellington, who’d be part of anything Wein produced, “is accustomed to being treated as royalty wherever he goes. He stays only in the finest hotels.” Wein detailed the saga of establishing Jazz & Heritage in his memoir, Myself Among Others: A Life in Music, and reports that the lunch ended with a consensus view “that the time had not yet come for a jazz festival in the South.”

By the time a fest was presented in 1968, it was Willis Conover, the renowned jazz host of the Voice of America (and a longtime emcee at Wein’s Newport Jazz Festival), who was hired to produce it. Wein learned through the grapevine that his own marriage to an African American, Joyce Alexander, “might be a political embarrassment to [New Orleans] Mayor Schiro if [he] were given the job,” so it went to Conover. It took only two years for the festival to become mired in local politics before the New Orleans Hotel Motel Association brought in Wein to run it once and for all. The festival is now owned by the non-profit Jazz & Heritage Foundation which is chaired by Quint Davis, the New Orleans native who’s been involved with the festival since its inception under Wein. But credit the respect Duke Ellington had earned elsewhere in the world with making it necessary for New Orleans to begin getting its act together before a bonafide jazz festival would be presented in the city of the music’s birth.