New England Milestones

Duke Ellington, whose 117th birthday anniversary is today, is rightly identified with the City of New York. The Washington, D.C. native made his first foray into the Big Apple in 1922, and from 1923 until his death 52 years later, New York served as both home and muse for this composer of such evocative pieces as “Echoes of Harlem,” “Wall Street Wail,” and “Uptown Downbeat.” Ellington’s theme song, “Take the ‘A’ Train,” composed in 1941 by his writing partner Billy Strayhorn, heralded the new subway line that carried passengers to Harlem. And “A Tone Parallel to Harlem,” an extended work commissioned for Arturo Toscaninni and the NBC Symphony in 1951, depicts in kaleidoscopic detail the black cultural capital where in 1927 Ellington began his ascendancy at the world-renowned Cotton Club.

But when it comes to Edward Kennedy Ellington, there is much for New England to celebrate too. Three of his most important sidemen, Harry Carney, Johnny Hodges, and Paul Gonsalves, had local origins. The study of Ellington’s music has been a part of the curriculum at the Berklee College of Music for over 50 years. His long summer residencies in the area in the mid-1920’s gave the band its first exposure outside of New York, and resulted in its first out-of-town reviews, one of which credited Ellington with “setting New England dance crazy.” In a 1930 article, Christian Science Monitor writer Janet Mabie suggested that Ellington’s royal moniker was inspired by his “great gift for understanding and his capacity for a very simple kind of friendliness.”

During his lifetime, Ellington received numerous honors and awards from area colleges and municipalities, including the Paul Revere Plaque from the City of Boston, honorary Doctor of Music degrees from Berklee, Assumption College, and Brown University, and the keys to the City of Worcester. In 1943, Boston was one of only three cities in which Ellington performed Black, Brown, and Beige, his sweeping tonal history of black America. He presented his Sacred Concerts, the liturgical works that occupied much of his writing during his last decade, at area churches. Of his 1962 performance with Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops, Ellington said he was “thrilled to tingling.”

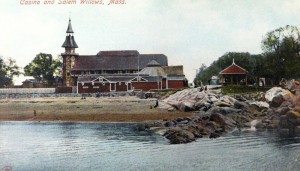

Back in the mid-1920’s, when Ellington was just beginning to gain a foothold in the New York nightclub world, he would spend the summer months playing a circuit of theatres, dance halls, and pavilions throughout Greater Boston. According to the late Mark Tucker’s Early Ellington, his itinerary for 1926 included 24 appearances in the area between July 12 and August 13. The following summer, he played 33 engagements around the Hub, including nine performances at the Charleshurst Ballroom in Salem Willows. Salem was the base of operations for Charlie Shribman, who operated a chain of ballrooms in New England and handled bookings for Ellington and other bands. In his autobiography, Music Is My Mistress, Ellington recalled Shribman as a man who “nursed” bands, “would send for them and keep them working…Yet (he) never owned a piece of any band or anybody …I cannot imagine what would have happened to the big bands if it had not been for Charlie Shribman.”

During the summer of 1926, 16-year-old Harry Carney from Cunard Street in Mission Hill played alto and baritone saxophones in the reed section of the Ellington band, spelling Otto Hardwick and making a favorable impression on the leader. Carney had begun piano lessons at age six, but after noticing that one of his boyhood friends, Buster Tolliver, “always seemed to be surrounded by the girls when he got through playing the clarinet,” he joined a Knights of Pythias band where he was trained on a variety of instruments, including clarinet. However, as he recollected in The World of Duke Ellington, Stanley Dance’s invaluable oral history, “After alarming the whole neighborhood with my practicing…I learned that saxophone was much easier…and because I played it so loudly, after-school jobs started to come in.”

In April 1927, Ellington offered Carney a permanent job with the band. “I was supposed to have returned to school,” he said, “but Duke, always…a fluent talker…out-talked my mother and got permission for me to stay with the band,” thus beginning a tenure that would last 47 years. Carney’s majestic baritone sax not only anchored the orchestra for nearly half a century, but his sound, which is without equal in jazz, provided Ellington with one of the richest colors in his tonal palette.

Rex Stewart, the trumpeter and Ellingtonian whose vivid writings on the jazz life were published in the collection Jazz Masters of the Thirties, suggested that Carney’s “career with Duke must set a record of some sort for longevity.” Stewart also surmised that Carney was “such a likable human being…since he is the product of a most harmonious household… His parents always extended themselves…every time we played Boston. (His) mother would put on a feast that even now makes my mouth water, especially those codfish cakes, hot rolls, and baked beans…Any member of the group who was ever exposed to the Carney hospitality has never forgotten it.”

Little wonder then that Ellington enthused over announcing to audiences that “Harry Carney has come all the way from Boston, Massachusetts, to lead us into ‘Jam With Sam’,” the tune that served as a roll call of the band’s great soloists. During the last two decades of their lives (Carney died within six months of Ellington in 1974), they traveled hundreds of thousands of miles together with Carney at the wheel of his Chrysler Imperial. “He’s a great fellow,” Carney said of his boss, “and it’s not only been an education being with him but also a great pleasure. At times I’ve been ashamed to take the money!”

And the money was considerable. But while Ellington earned large sums from royalties on his popular songs– “Mood Indigo,” “In A Sentimental Mood,” “I’m Just a Lucky So and So,” “Do Nothin’ Till You Hear From Me,” “Prelude to a Kiss,” “Satin Doll,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore”- he poured his earnings back into the operation to keep his well-paid orchestra, his “sounding board,” on tap so he could hear his music as it was being created.

“Ellington plays the piano,” Billy Strayhorn famously observed, “But his real instrument is his band.” And rarely in the history of music have composer and orchestra been so interdependent. Ellington’s uniqueness grew out of his interest in the musical personalities he both led and collaborated with. Indeed, he was fond of saying that he had to know how a man played poker before he could write for him. As for the bottom line, he said, “By various twists and turns, we manage to stay in business and make a musical profit. And a musical profit can put you way ahead of a financial loss.”

The highest paid of all Ellingtonians was Johnny Hodges, the tight-lipped, glum-faced saxophonist who, in trumpeter Shorty Baker’s estimation, produced “a million dollars’ worth of melody.” Born in Cambridge in 1906 and raised a few blocks from Carney on Hammond Street, Hodges began playing the soprano saxophone at age 12. He met Sidney Bechet when the New Orleans jazz pioneer was playing in a Scolley Square burlesque house in 1924. Bechet dated Hodges’ sister while he was in town, and her gutsy younger brother approached the great master and rendered a version of “My Honey’s Lovin’ Arms” that elicited encouraging words from Bechet.

Hodges joined Ellington in 1928, and but for a brief period in the early ’50’s when he fronted his own combo, his boss enjoyed “the privilege of presenting (him) night after night for forty years. I imagine I have been much envied,” Ellington reflected when Hodges died in 1970. Throughout his career, Ellington and his writing partner Billy Strayhorn fashioned dozens of ballads and blues to showcase the exquisite sensuality and jesting wit of Hodges, whom Ellington eulogized as a player of “pure artistry…a beautiful giant in his own identity.”

Nat Hentoff remembers hearing the Ellington orchestra on many occasions at the Roseland State Ballroom on Mass Avenue (now the site of Christian Science Park) in the early ’40’s. “I didn’t dance then, still don’t, but I’d tuck my chin on the edge of the bandstand, and I’d ask Carney the names of these new tunes I didn’t recognize. Often they’d be so fresh that he’d only know them by a number. They hadn’t been titled yet.”

An ardent civil libertarian who’s long been inspired by the jazz artist’s devotion to freedom of expression, Hentoff worked as an announcer at WMEX, which broadcast from the Savoy nightclub on Columbus Avenue, and while attending Northeastern and Harvard, he befriended Rex Stewart, whom he remembers as being ” as sharp as any political analyst I’ve ever met.” A 17-year-old Hentoff also caught Ellington’s January 28, 1943 concert at Symphony Hall, one of only three venues at which Duke gave complete performances of Black, Brown, and Beige, his ambitious 43-minute long “tone parallel to the history of the American Negro.” Five nights before the Boston performance, Ellington presented its premiere at Carnegie Hall and was stung by the patronizing reviews he received from the classical music critics in attendance.

Hentoff retains a vivid memory of the Boston premiere, which he walked to from his boyhood home on Howland Street in Roxbury. “There was a terrible blizzard that had paralyzed the city that day, and everybody thought I was crazy to go. I didn’t expect much of a turnout, but when I got there I was stunned to see that it was packed. I’d been at Symphony Hall just a couple of weeks earlier to hear Serge Koussevitsky conduct Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which of course was very exhilarating. But the Ellington gave me a similar feeling, and I hardly remembered the icy walk home.”

Hentoff eventually became a confidant of Ellington’s. In 1965, when this composer of nearly 2,000 published works, arguably the most significant body of American music yet produced, was denied a special Pulitzer Prize in recognition of his lifetime achievement, he expressed his disappointment with mocking irony: “Fate is being very kind to me. Fate doesn’t want me to be too famous too young.” Ellington was 66 at the time. But as Hentoff relates in his book Listen to the Stories, a few nights later, a “coldly angry” Ellington told him, “Most Americans still take it for granted that European-based music is the only really respectable kind. What we do, what other black musicians do, has always been treated like the kind of man you wouldn’t want your daughter to associate with.” (In 1999, his centennial year, an honorary Pulitzer Prize was finally awarded to Ellington; it was terribly overdue, and hardly noticed.)

Paul Broadnax, the singer and pianist who was born in Cambridge, remembers seeing Ellington for the first time in the early ’40’s at the RKO Theatre (now the WangCenter) on Tremont Street. “We took great pride in Ellington, whom I met but mostly adored from afar. This was still a time of extreme segregation, and very few jobs were available for black musicians on the local hotel dance scene. Most of the work for us was in the nightclubs around Columbus and Mass Ave., the Savoy, the Hi-Hat, Eddie’s, Wally’s Paradise. Ellington was first class, and he played the top spots. The band always looked great, they wore beautiful tuxes, nothing rag-tag, and the music just blew our minds. But the social thing was very important. Duke gave us a great feeling.”

Broadnax had begun his career writing arrangements for Sabby Lewis, Boston’s premier black bandleader, in the late 1940’s. Lewis’s star soloist was tenor saxophonist Paul Gonsalves, the New Bedford native whom Broadnax recalls as “an incredible player who could lift that whole band. He had such a great sound, and he was full of ideas, very, very advanced.”

Gonsalves joined Ellington in 1950, and six years later his electrifying 27-chorus-long solo on the interval connecting “Diminuendo in Blue” and “Crescendo in Blue” highlighted Ellington’s triumphant appearance at the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival. The concert so revived Ellington’s sagging fortunes that he took to describing himself as having been “born in Newport, Rhode Island in 1956.” Ellington remained particularly beholden to Gonsalves from thereon, tolerating the saxophonist’s errant behavior both on and off the bandstand and indulging him like a profligate son. Gonsalves died in London only days before Ellington on May 15, 1974, and they were waked together in New York.

The late trumpeter and educator Herb Pomeroy, who spent several years on the road with Lionel Hampton and Stan Kenton before embarking on a 40-year-long teaching career at the Berklee College of Music, experienced Ellington from two perspectives. In the late ’50’s, Pomeroy established a seminar on Ellington at Berklee, the only course of its kind in the country at the time. Duke’s unconventional composing and arranging styles, described by Pomeroy as “trial and error, seat-of-the-pants,” baffled other musicians for years, perhaps even Ellington himself, who was notoriously tongue-in-cheek. “On one of the early occasions when we met,” he recalls, “Duke said, ‘Herb, I understand you’re teaching a course on me up there in Boston. Maybe I should come up and take it in order to find out what I’m doing.”

Pomeroy also played with the Ellington orchestra on numerous occasions, spelling the veteran trumpeter Cootie Williams. His first time with the band was unforgettable. “We were playing the Starlight Lounge in Peabody, and I’m playing Cootie’s book. You know, even with Duke it wasn’t all concert halls and festivals. He had to have a book for country club dances and proms, and as I was looking through Cootie’s book I noticed some music by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, “Tijuana Taxi,” as I recall. I thought, ‘My God, the great Cootie Williams has to play this stuff.’ I’m expecting a night of “Cottontail” and “Harlem Air Shaft.” Well, after awhile, Duke introduced me as a new member of the band, saying ‘Ladies and Gentleman, Herb Pomeroy wants you to know that he loves you madly and he would like to play “Tijuana Taxi” for you.’ Well, I was so taken aback that I got out my plunger and played something– whatever it was, it wasn’t very sincere. But I got through it. And then Duke thanked the audience for their kind applause and reminded them that ‘Herb Pomeroy still loves you madly, and now he would like to play “Tijuana Taxi” for you once more.’ You know, it was Duke’s way of saying, ‘Welcome to the band, Herb’!”

Pomeroy survived this innocuous hazing ritual and remained wide-eyed in his appreciation of Ellington. “I was like a kid in a candy store every time I played on that band,” he says. “I was checking out everything. The band itself was like a vibrant human animal.”

Among the dates Pomeroy played with Ellington was one of the series of summer concerts presented by Elma Lewis in Franklin Park during her annual Marcus Garvey Festival. This was a highly favored venue of the Ellingtonians, who enjoyed the relaxed, down home air of the event and the opportunity it afforded for reunions with old friends and family. In Music Is My Mistress, Ellington described Lewis, who was one of the invitees to his 70th birthday party at the Nixon White House, as “the symbol of Marcus Garvey come alive and blazing into the future of the arts. Her cultural center in Roxbury is above and beyond abnormal expectancy.” He happily recalled the orchestra’s “wonderful reception…and the soul supper afterwards.”

May 24 will mark the 40th anniversary of Duke Ellington’s death at age 75, but his stature only grows with the passage of time. Biographies of Ellington by James Lincoln Collier and Terry Teachout, and David Hajdu’s biography of Strayhorn, Lush Life, have sought to question his skill and originality as a composer. Meanwhile, Ellington’s music sounds as vital as ever, whether in performances by Wynton Marsalis and the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, or in the current Broadway production, After Midnight.

Since his death, New York City has honored Ellington’s memory by naming two streets on the Upper West Side– Duke Ellington Circle and Duke Ellington Boulevard– after him. In 1997, a two-story statue of Ellington was unveiled in the northwest corner of Central Park.

Given his substantial ties to the Hub, it would hardly seem out of place for a bust of Ellington to someday grace this city of statues. The Commonwealth Avenue Mall would be a most appropriate location, 18 stories below the rooftop of the Ritz Carlton, where in 1935 Ellington became the first black musician to lead an orchestra. And if not Duke, how about commemorating the Bostonians Hodges and Carney? Mayor Marty Walsh must surely have heard of them.

[Note: A portion of this article appeared in The Boston Globe Magazine on December 26, 1999.]