Today is the 90th birthday anniversary of Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis. Had the saxophonist been a Texan, he’d be one of the most celebrated of the Texas Tenors. But because he was a New Yorker, a new alliterative appellation was coined to describe his place in the tradition: Tough Tenor. Jaws was tough, alright. As you’ll see in this performance of “Cherokee” with Count Basie, he played with a biting attack and swaggering nonchalance that belied the incredibly challenging nature of the music.

As Davis told Stanley Dance in The World of Count Basie , his approach was wholly deliberate. “I handle the horn the way I do to show I’m its master! I’ve always noticed how delicately so many tenor players handle it, as though it were fragile, as though it commanded them. I try to show that I have command of the horn at all times. The visual impression is quite important…I want the audience to feel I am in complete command.”

It was this commanding authority that led Teddy Hill, the manager of Minton’s Playhouse in Harlem, to have Jaws police the bandstand when Minton’s was a hotbed of jam session activity in the ‘40’s and ‘50’s. Davis told Art Taylor in Notes and Tones that when he was headlining the room, Hill told him he couldn’t manage both the club and the bandstand, so he turned it over to Jaws to decide who was fit for action. “It became a sticky job,” Davis said, “because with a guy who thinks he’s qualified and who isn’t, it becomes very embarrassing to have to ask him off the stand. There were times when it almost became violent.”

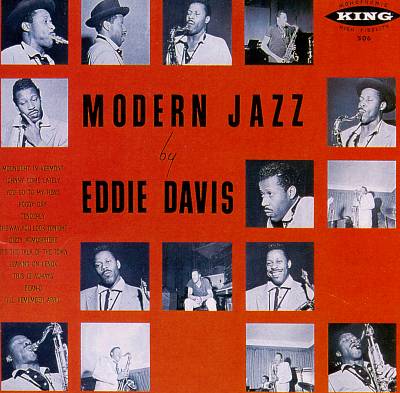

Jaws earned his stripes in the white heat atmosphere of bebop’s early years, working with the big bands of Cootie Williams and Andy Kirk between 1942 and ’46, and then recording under his own name with Fats Navarro and Bud Powell. Bebop induced an earnest demeanor in many of its exponents, but Davis managed to combine his modernist leanings with the exuberance he observed in models like Ben Webster and Illinois Jacquet .

As he told Taylor, “There was a different atmosphere about jazz years ago. The players themselves projected lighthearted feelings. There was a margin of humor in playing; there was a happier atmosphere. Today the jazz musician comes to the bandstand with a grim outlook; he’s too serious. This is infectious. The people who come to the club are afraid to talk, afraid to laugh among themselves…so the joint looks like a graveyard. Jazz was never meant to be that way. To me jazz has always meant an outlet, a form of expression, a relief, a relaxation and a listening pleasure. It ought to be a pleasant experience, not grim. “

Nothing less than pleasurable music spilled out of the bell of Davis’s horn for over forty years. He began an intermittent association with Count Basie in 1952 that lasted into the ’70’s, and at various points he served as the band’s road manager. (In the mid-’60’s, disillusioned with how much the avant-garde had displaced mainstream jazz in terms of press and bookings, he hung up his horn for a couple of years and utilized his business acumen as an agent with Shaw Artists. )

In 1955, Jaws established one of the first tenor and organ trios when he teamed with Shirley Scott for several years; here they are in 1958 playing “Skillet,” a slow burner from their Prestige LP, The Cookbook, Vol. 2. In 1960, he formed a two-tenor combo with Johnny Griffin that made one of the first recordings devoted exclusively to Thelonious Monk’s music. Griff and Jaws also recorded on location during a long run at Minton’s. Here they are a couple of decades later in Scandinavia playing “Funky Fluke” with Harry Pickens, Curtis Lundy, and Kenny Washington.

And here’s a short clip of latter-day Lockjaw smokin’ with Oscar Peterson, Niels Pederson and Bobby Durham.

I saw Jaws when he was touring with Harry “Sweets” Edison in the late ‘70’s at the El Morocco in Worcester. On that occasion, courtesy of Worcesterite Mary Mardirosian, a personal friend of Basie and a couple of generations of his sidemen, I was invited to dinner with these two legends. The garrulous Lockjaw I met that memorable Monday night seemed every bit the man who concluded his interview with Art Taylor with a frank admission of what drew him to jazz in the first place. “By watching musicians [when I was young] I saw that they drank, they smoked, they got all the ladies and they didn’t get up early in the morning. That attracted me. My next move was to see who got the most attention, so it was between the tenor saxophonist and the drummer. The drums looked like too much work, so I said I’ll get one of those tenor saxophones. That’s the truth. “