Evans/LaFaro/Matthiessen/Jarrett

I’ve been working on a Scott LaFaro blog, and yesterday read of how he got turned on to Zen meditation through Bill Evans. In a letter written in 1960 in which he wondered if his dedication to jazz was worthwhile, Scotty took heart in this Zen epigram: “If you seek the fruits of good action so shall they escape you.”

That same year, Evans told Downbeat. “I don’t pretend to understand [Zen]. I just find it comforting. And very similar to jazz. Like jazz, you can’t explain it without losing the experience. That’s why it bugs me when people try to analyze Jazz as an intellectual theorem. It’s not. It’s feeling.”

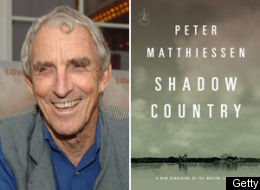

When I finished yesterday’s writing on LaFaro, I read the Sunday Times Magazine profile of Peter Matthiessen, which recounts his long devotion to Zen and mentions the frustration he had in putting it into words: “You try to explain, and then it’s ‘Oh crap, what am I saying’?” The article’s author, Jeff Himmelman, went on to call Zen practice rituals, “robes, chanting, bowing, long periods of silence…structures,” and likened them to the “musical structures that underlie jazz. They are there to fall back on, and to make you free.”

As it happened, Matthiessen died on Saturday, so yesterday’s paper also carried his obituary. How Zen is that? The obit concludes with this quote from a 2002 article on Matthiessen for The Guardian. “Zen is really just a reminder to stay alive and to be awake. We tend to daydream all the time, speculating about the future and dwelling on the past. Zen practice is about appreciating your life in this moment. If you are truly aware of five minutes a day, then you are doing pretty well. We are beset by both the future and the past, and there is no reality apart from the here and now.” Today’s Fresh Air offered this reprise of Terry Gross’s interview with Matthiessen in 1989. The topic was writing and Zen.

In a 2007 article published in Tokyo, Keith Jarrett: Zen in the Art of Jazz, C. B. Liddell wrote, “Like Zen, jazz develops a loose, all-embracing awareness of its subject and a lack of premeditation that allows the musician to suddenly strike the right note. Regarding Japanese Zen philosophy, Jarrett explains that, as with his musical influences, he has not been directly influenced. But, as an attitude that can be applied to different aspects of life, Zen is something that clearly resonates strongly with him. ‘Those Zen paintings made with one brushstroke after years of meditation, were always very striking to me,’ he reveals. ‘They are not touching the page, then they are, then they are not: and that is exactly what happens when one is truly improvising – you are touching the whole thing, and then it’s gone’.”

Jarrett here echoes Evans’s liner note essay for Miles Davis’s Kind of Blue in which he compared Japanese Zen painting with the art of spontaneous improvisation embodied by the Davis masterpiece. This clip of Bill being interviewed by his brother Harry shows the pianist illustrating a point about the authenticity of the creative process with “How About You,” a quintessential New York song. Who knows but that New Yorker Matthiessen knew it well?