I’d never noticed until I heard the All Things Considered report on Wednesday that two recordings I’ve listened to for years, Robert Johnson’s “Kind-Hearted Woman” and Pablo Casals’ performance of Bach’s Suites for Cello, were made on the same day, November 23, 1936. It’s easy to think of these as disparate forms of expression recorded worlds apart from each other, Johnson in a San Antonio hotel room and Casals at the Abbey Road Studio in London. But as cellist Bernard Greenhouse says in the report, “Music is a language which transcends all people, all parts of the world, a language which is almost understandable word for word.” Listen here to the report and a moving example of this harmonic transcendence as Johnson’s “Come On in My Kitchen” and the Cello Suite are combined at the conclusion of this fascinating story.

The Johnson myth has captivated me ever since I first heard the King of the Delta Blues Singers 44 years ago. I’d already heard Johnson’s blues played by Muddy Waters, Paul Butterfield, and Cream, but the 1936-’37 originals transported me to a world as mystifying and forbidding as any I’ve ever encountered on record, the haunted vision of a 25-year-old black man born in Mississippi in 1911. Bob Dylan heard the LP upon its release in 1961, and remembered it vividly in his 2004 memoir, Chronicles, Volume One, as “fires of mankind blasting off the surface of this spinning piece of plastic.”

Those fires were brought a little closer to home for me about 20 years ago when I met Annye C. Anderson, an Amherst resident who’s the half-sister of Johnson’s half-sister Carrie Thompson. Anderson was at the Iron Horse to hear the bluesman Robert Jr. Lockwood, who had a substantial connection of his own to Johnson. Lockwood’s mother and Johnson were involved on and off for several years, and while Robert was named Junior for his father, he adopted the moniker Robert Jr. to underscore his connection with the legendary bluesman. Johnson was a rambler who reportedly made a practice of seeking the company of older women; Mrs. Lockwood was about 15 years his senior, and Robert Jr., born in 1915, was only four years younger and already playing guitar when Johnson entered the Lockwood household. In 1941, three years after Johnson’s murder, Lockwood recorded “Take a Little Walk With Me,” which may have been composed by but went unrecorded by Johnson. Lockwood remained a living touchstone to the Johnson legend for decades thereafter, and occasionally teamed with another of Johnson’s proteges, Johnny Shines, in the 70’s and 80’s.

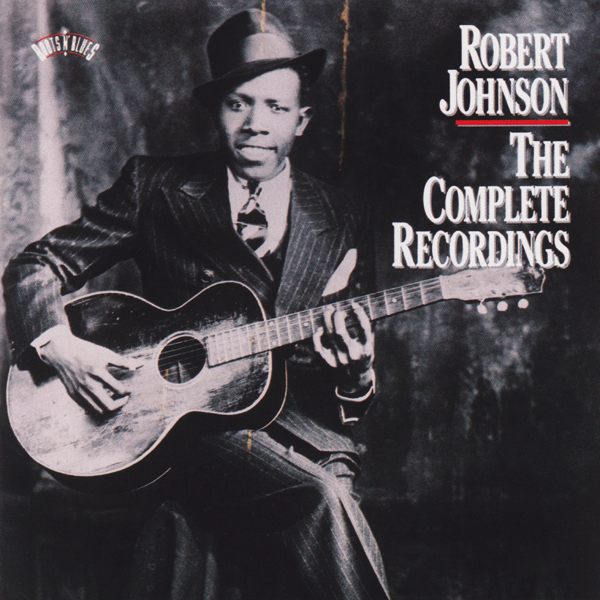

Annye Anderson became an heir and executor to the Johnson estate when Carrie Thompson died in 1983. Several years later Sony Music reissued Johnson’s complete recordings (29 masters and 12 alternates) to much fanfare. Blurbs by Keith Richards and Eric Clapton jumped off the cover of the boxed-set and helped propel its phenomenal success. Various screenplays, a movie, a few books and more ensued, and in the wake of this renewed interest in Johnson, a new claim was made on his estate by Claud Johnson, a man whose mother had had a relationship with Johnson in 1931, the year of Claud’s birth. The next decade brought a series of probate claims and counter-claims in the Mississippi trial courts, rejected appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court, and ultimately a decision by the State Supreme Court of Mississippi in 2000 that named Claud Johnson as sole heir and granted him an initial award of $1.2 million in royalties.

Needless to say, this is a quick summary of a tale of labyrinthine proportions. Further details on the court verdict are available here. A comprehensive treatment and updating of Johnson’s legacy was published in Vanity Fair in November 2008. Read Frank DiGiacomo’s account here.

And if you ever puzzled over the high pitch of Johnson’s singing, there’s new speculation that Columbia released his work at the wrong speed. Here’s a report from the Guardian which includes a few samples of Johnson’s work slowed down and quite possibly as he intended to be heard.