Herb Pomeroy’s April 15th birthday often coincides with the statewide Patriot’s Day holiday commemorating the “the shot herad ’round the world” that triggered the American Revolution. The trumpeter and educator was born in Gloucester on April 15, 1930, came to the Connecticut River Valley to attend Williston Academy in Easthampton, and after a year at Harvard, where he went to prepare for a career in dentistry, Herb made a midnight ride across the Charles to study music at Schillinger House in Boston’s Back Bay. Schillinger was the precursor to Berklee, which later became virtually synonymous with Pomeroy during his 40-year tenure as director of its Jazz Studies program.

Before joining the Berklee faculty, Herb toured with Lionel Hampton and Stan Kenton; shared the front line with Charlie Parker on Bird’s Boston gigs; and was at the center of the Hub’s dynamic post-war jazz scene. Pomeroy was a fixture at The Stable, the home of modern jazz in Boston. In his guide to jazz in the Hub, The Boston Jazz Chronicles, 1937-1962, Richard Vacca clarifies that what’s come to be known as the Herb Pomeroy Quintet was generally billed as the Jazz Workshop Quintet, a combo that coalesced around Pomeroy, saxophonist Varty Haroutunian, pianist Ray Santisi, bassist John Neves, and drummer Jimmy Zitano. The quintet’s 1955 album, Jazz in a Stable, garnered a five-star review in Downbeat, and a Metronome review singled out Herb as “certainly the standout.” Their performance of the Kansas City jazz evergreen, “Moten Swing,” underscored Metronome’s assessment of the quintet’s take on modern jazz as “almost always exuberant.”

The Back Bay club also fostered Benny Golson’s classic tune, “Stablemates.” In Golson’s autobiography, Whisper Not, he wrote that while touring with saxophonist Earl Bostic, “[We] played Boston quite a bit, and I had come to know Herb Pomeroy…who worked with a very congenial bunch of guys at a club called The Stable…Herb…asked me to write a piece for his group, his Stable mates, as it were…Pleased, I sent him this obtuse song, born from my mad scribbling…The song had caused me a great deal of wrangling, and it didn’t have a name. But Herb loved it. It was odd and angular, not because, as Miles Davis later kidded me, I smoked funny stuff, but because I wrote it in a strange mood in a strange place, in an emotional tight spot…I wrote a song with a kind of ugly beauty. Creativity is perverse and marvelous and enigmatic. The song, of course, was ‘Stablemates’.”

In a 2018 interview with Matthew Kassel at Vulture, Golson said, “Well, what really got me started was when Miles Davis record “Stablemates.” When John Coltrane left to join Miles, I saw him one week later on Columbia Avenue, the street in North Philadelphia where John and I lived — I lived on 17th Street; he lived on 12th Street. I asked him how it was going with Miles because I knew he had to come abreast with the repertoire, and he said it was going good. Then he added, ‘But Miles needs some tunes, do you have any?’ Are you kidding? I had written this oddball tune called “Stablemates.” John took it with him, and I didn’t think any more of it because nobody was recording anything of mine…Then I ran into John about a month later, and he said, ‘Guess what?’ I said, ‘What, he do that tune I gave you?’ He said, ‘Yeah, we recorded it!’ I said, What? Miles recorded my tune?’ He said, ‘Yeah, Miles dug it.’ And when I saw Miles, Miles said to me, ‘What were you smokin’ when you wrote that’?”

Miles made an early recording of “Stablemates,” with his newly formed quintet with John Coltrane in 1955, but Pomeroy made its premier recording on Jazz in a Stable. And it was at the 20 Huntington Avenue venue where he soon began leading the big band that would record two legendary sessions in the late ’50s, Life Is A Many-Splendored Gig and Band in Boston. The Pomeroy orchestra also backed vocalist Irene Kral on her 1958 debut, The Band and I. For Many-Splendored…, Zoot Sims was added as tenor soloist in a section that also included pianist Jaki Byard; the Worcester native played tenor on the album while Santisi held the piano chair. The album introduced Byard’s composition, “Aluminum Baby.”

Elsewhere on record, Pomeroy can be heard on various Charlie Parker radio broadcasts from the Hi-Hat and Storyville in 1953, He was a member of the Serge Chaloff Sextet that recorded two essential documents of Beantown jazz, The Fable of Mabel in 1954, and Boston Blow-Up, in ’55. And on one of his rare out-of-town dates, he’s featured with Paul Gonsalves on “Body and Soul,” and with Eric Dolphy and Benny Golson on “Afternoon in Paris” and “The Stranger” on John Lewis’s 1960 classic, The Wonderful World of Jazz.

Dick Vacca’s Boston Jazz Chronicles offers a richly detailed, profusely illustrated account of the Boston jazz scene between 1937 and ’62, and he devotes a chapter to the Stable as well as the Jazz Workshop. The Workshop was a cooperative housed at 20 Stuart Street that offered classes and private instruction in an atmosphere that saxophonist Charlie Mariano said “simulated on-the-job conditions.” Established in 1953, its faculty also included Jaki Byard, Ray Santisi, and Pomeroy, and Nat Hentoff touted it in Downbeat as “a striking new concept of jazz instruction.” What Vacca calls “the right idea in the right place at the right time,” eventually lost its footing when Mariano and Pomeroy hit the road, the former for Kenton, the latter, along with Boston piano legend Dick Twardzik, for Lionel Hampton’s Orchestra. Nonetheless, when Schillinger president Lawrence Berk invited Santisi to conduct Workshop-style sessions on Saturday afternoons at the school, the “new concept” proved to be a prototype for Berklee’s eventual emphasis on jazz.

After his tours with Hamp and Kenton, Herb began teaching at Berklee in 1956; he also founded the MIT-based Festival Jazz Orchestra in 1963. Among his groundbreaking initiatives in jazz education was a course on Duke Ellington which he introduced in 1958. When I spoke with Pomeroy 15 years ago for a Boston Globe article about Ellington in New England, he said that Duke’s unconventional arranging and composing styles, which he described as “trial and error, seat-of-the-pants,” baffled other musicians, and Ellington loved to play along. Herb recalled, “On one of the early occasions when we met, Duke said, ‘Herb, I understand you’re teaching a course on me up there in Boston. Maybe I should come up and take it in order to find out what I’m doing’.”

(Duke and Herb with a Berklee student ensemble)

Pomeroy later became a sub with the Ellington orchestra, on occasion spelling the veteran trumpeter Cootie Williams. His first night with the band was humbling and memorable.

“We were playing the Starlight Lounge in Peabody, and I’m playing Cootie’s book. You know, even with Duke it wasn’t all concert halls and festivals. He had to have a book for country club dances and proms, and as I was looking through Cootie’s book I noticed some music by Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, “Tijuana Taxi,” as I recall. I thought, ‘My God, the great Cootie Williams has to play this stuff.’ I’m expecting a night of “Cottontail” and “Harlem Air Shaft.” Well, after awhile, Duke introduced me as a new member of the band, saying ‘Ladies and Gentleman, Herb Pomeroy wants you to know that he loves you madly and he would like to play “Tijuana Taxi” for you.’ Well, I was so taken aback that I got out my plunger and played something– whatever it was, it wasn’t very sincere. But I got through it. And then Duke thanked the audience for their kind applause and reminded them that ‘Herb Pomeroy still loves you madly, and now he would like to play “Tijuana Taxi” for you once more.’ You know, it was Duke’s way of saying, ‘Welcome to the band, Herb’!”

Pomeroy survived this innocuous hazing and remained wide-eyed in his appreciation of all things Ellingtonia. “I was like a kid in a candy store every time I played on that band,” he says. “I was checking out everything. The band itself was like a vibrant human animal.”

Herb figures prominently in Jack Chambers’s superb biography Bouncin’ With Bartok: The Incomplete Works of Richard Twardzik. Chambers’s sensitive, musically-astute account of the ill-fated pianist’s life is one of the most absorbing jazz biographies ever published, and among its highlights is a comprehensive look at the Boston scene in the 40’s and ’50’s, and a revealing view of the Boston bohemia that Twardzik’s artist parents were part of in the ’20’s and ’30’s. Pomeroy’s friendship with and devotion to Twardzik, who died of a drug overdose in 1955 at age 24 while on tour with Chet Baker in Paris, included an annual pilgrimage to his gravesite. The telling will tug at your heart.

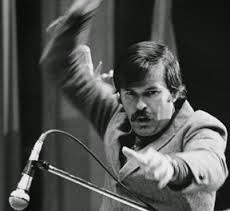

The mustachioed trumpeter with the pronounced North Shore accent remained a highly visible figure on bandstands around Greater Boston during his four decades at Berklee. He maintained his big band through the years, and in 1980 began a long residency on Monday nights at the El Morocco in Worcester. He often spoke of the challenge presented in trying to improvise fresh ideas and melodies, and occasionally chided himself for falling back on bebop licks that he’d mastered early in his career. His recorded output was frustratingly small, but what’s there is superb, from the Stable date and the ‘50’s big band sessions, to his later recordings with vocalists Paul Broadnax and Donna Byrne, saxophonist Billy Novick, and a couple of big band sets recorded at the now-defunct El.

Wall Street Journal contributor Marc Myers publishes the daily, must-read blog, JazzWax. Marc has kindly flagged the NEPR jazz blog in WeekendWax, and here are links to three highly appreciative posts that he’s published on Pomeroy. It’s great to see a native New Yorker paying such attention to the Boston scene, and JazzWax reader comments add a good deal to the story as well. Here’s Marc’s post on Life Is a Many-Splendored Gig; here’s his memorial to Herb, who died in 2007; and here’s a blog devoted to Pomeroy’s big band recording, Pramlatta’s Hips.

73-year-old Herb and 78-year-old Brockton-born saxophonist-clarinet player Dick Johnson are seen here in 2003 playing Duke Ellington’s “In a Mellow Tone.”