I spent a horribly jazz-deprived time in Eugene, Oregon, in 1977, where the only saving grace was the Prez Records shop, which was named for Lester Young and operated by a true believer. But over the length of the fall semester, there was only one area performance by a jazz combo. It was led by the late Stan King of Portland, and given the subject of this blog, it’s worth noting that it featured Marty Ehrlich, who was just then emerging from the New England Conservatory, where he was a star pupil of Jaki Byard. When I flew into Boston for the Christmas holidays that year, I made sure to arrive on a Wednesday so that I could see Byard leading his big band, The Apollo Stompers, which had formerly included Ehrlich, at Michael’s Pub on Gainsborough Street. The band was stocked with NEC students, and even though they were young and unseasoned, under Jaki’s direction they congealed into a dynamic outfit with a fascinating repertoire. (Byard also maintained a New York edition of the Stompers that was staffed by professionals and recorded for Soul Note Records.)

Before leaving for the West Coast that summer, Michael’s had been a regular stop for me on Wednesday nights. The place was a shot-and-a-beer dive with leaky ceilings and overhead steam pipes under which spaghetti pots were strategically placed to collect dripping water. Students from nearby NEC and Northeastern wandered in at night and spruced it up a bit, and the Stompers gave it a big lift on Wednesdays.

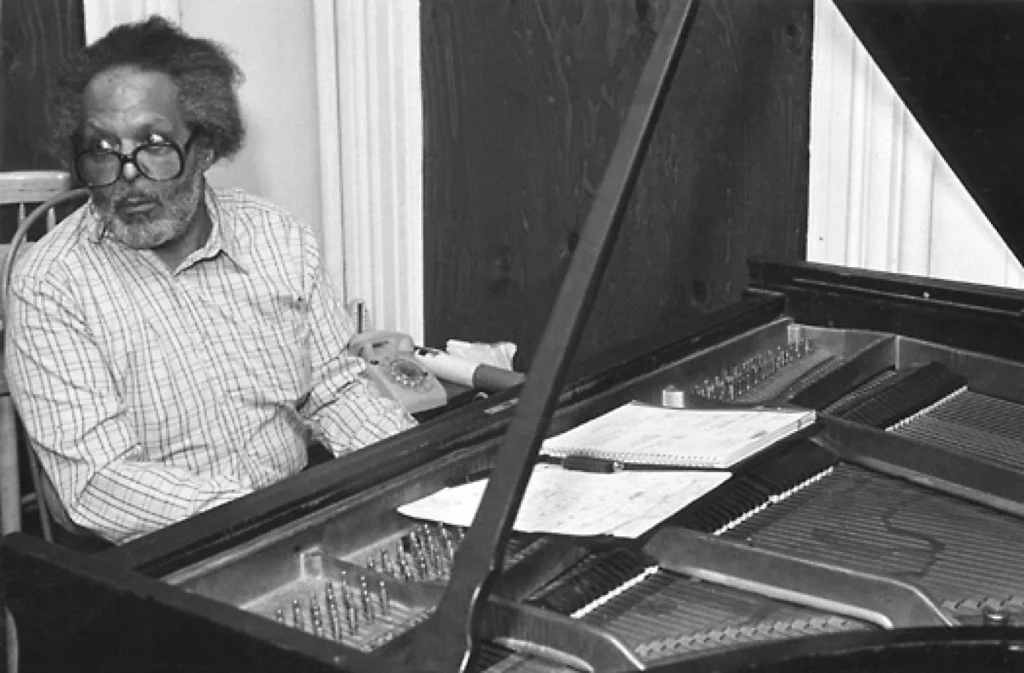

June 15 was John Arthur Byard’s 95th birthday anniversary. Like me, he was born in Worcester, and he blazed his own trail out of town, so I’ve felt a desire to celebrate Jaki ever since I became aware of him. I love his eclecticism, his unpredictability, his restless engagement with tradition, his humor, even his sarcasm, which he displays in a twelve-second intro to a Thelonious Monk medley he played at Maybeck Recital Hall in 1991. Jaki tells the audience, “There was a composer in Paris [who] was commissioned to write a composition for some big shot for the left hand, so I’m going to do this thing just with my left hand only,” then proceeds into “’Round Midnight.” Jaki’s “big shot” rings with a Worcester-accented clarity that resonates with the kinds of taunts I heard on the streets of my old hometown.

Chet Williamson, the Worcester-born jazz harmonica player, has been a custodian of Byard’s legacy since his death by gunshot at his home in Queens in 1999. As the New York Times obituary by Peter Keepnews reported in 1999, “Police are investigating the death of Mr. Byard, who was found shot in the home he shared with his two daughters. Denise Byard-Mitchell, one of his daughters, said the family was baffled by the killing, and that she and other family members had been home when Mr. Byard died and had heard nothing.” The case remains “open” and unsolved eighteen years later.

Williamson’s research and writings on Byard’s Worcester background, including his co-founding in 1938 of the Saxtrum Club, a cooperative established by the city’s black musicians, and a video-taped symposium he hosted on Byard at WPI in 2001, are a cornerstone of WPI’s Jazz History Database. Here’s a montage he put together of images from Jaki’s Worcester days.

In a 1979 interview with W. Royal Stokes, Jaki discussed his early experiences seeing bands in the mid-’30s. “My mother used to give me seventy-five cents to go see the bands that were playing at Quinsigamond Lake — ten cents for the streetcar each way, fifty cents to get into the dance, five cents for a coke. I would walk to the dance so that I could drink five cokes. I’d stand in front of the band all night and listen. Fats Waller, Lucky Millinder, Chick Webb with Ella Fitzgerald, the Benny Goodman Quartet with Teddy Wilson, Lionel Hampton, and Gene Krupa. That would be about 1936. And I was tuning in on the radio broadcasts of the big bands from hotels, 11:30 p.m. to 2:00 a.m. Ellington, Basie, Fatha Hines, Jimmie Lunceford, Benny Carter. Those were the things that inspired me. I guess it stuck with me.” (Incidentally, Stokes continually refers to Jaki’s hometown as Boston rather than Worcester, New England’s second largest city 40 miles to the west.)

Byard also figures prominently in a lively and resourceful book by Richard Vacca, The Boston Jazz Chronicles: Faces, Places, and Nightlife 1937-1962. Vacca’s chapter on Byard begins with Nat Hentoff’s assertion that Jaki “was a pervasive influence on nearly every young Boston jazz musician who was interested in discovering new jazz routes.” Following his Army service in World War II, Byard toured with Earl Bostic, then was on the Boston scene throughout the late ’40s and ’50s where he played with Ray Perry, Jimmy “Bottoms Up” Tyler, Herb Pomeroy, Charlie Mariano, Sam Rivers, and Jimmie Martin’s 17 Exponents of Bebop, a band that included Gigi Gryce and Joe Gordon. He led his own trio at Wally’s, a big band at the Buckminster Hotel, and was the “intermission pianist” at the Stable in Copley Square. He was also at the center of activity at the Melody Lounge in Lynn, a venue favored by the modernists. (Danvers-born piano phenom Dick Twardzik, who died from a heroin overdose at 24 in Paris while touring with Chet Baker, was often there too.)

During his Boston years, two of Byard’s compositions were recorded. “Diane’s Melody” (named for his wife, and one of numerous works dedicated to family members) was introduced on Serge Chaloff’s 1955 album, Boston Blow-Up. Three years later, “Aluminum Baby,” appeared on Herb Pomeroy’s big band album, Life Is a Many-Splendored Gig. Jaki plays tenor on the date while another Boston legend, Ray Santisi, is at the piano. Here it’s played by Fred Hersch and the NEC Jazz Orchestra.

Jaki’s legacy is also the raison-d’etre of Yard Byard, a quintet featuring George Schuller on drums, Jamie Baum, alto flute, Jerome Harris, guitar, Ugonna Okegwo, bass, and Adam Kolker, tenor saxophone/bass clarinet. Here they play Byard’s “Inch By Inch.”

Byard went on the road in 1959 with Maynard Ferguson’s big band as pianist and arranger. The following year, aged 38, he recorded his first album, Blues for Smoke, which Nat Hentoff produced for Candid. In December 1960, he played on Eric Dolphy’s album Far Cry, which introduced two of Jaki’s most celebrated compositions, “Mrs. Parker of K.C.,” and “Ode to Charlie Parker.” It also introduced Byard to Prestige Records, the label he would record several outstanding albums for over the next decade. In 1962, he joined Charles Mingus, with whom he toured extensively until Mingus took a break from the scene around 1967. Given their mutual interest and deep knowledge of pre-modern jazz styles and post-modern concepts, they were a natural match, and his association with Mingus remains the most prominent of Byard’s career. Jaki arranged several pieces, including “Meditations on Integration,” for the landmark concert and album Mingus at Monterey. Most of the horn players on Byard’s Prestige albums, Dolphy, Richard Williams, Booker Ervin, Jimmy Owens, and Roland Kirk, were also Mingus associates.

Here’s Jaki with Mingus, Dolphy on bass clarinet, Clifford Jordan on tenor saxophone, Johnny Coles on trumpet, and drummer Dannie Richmond playing “Take the A Train.” Note the look of delight on Mingus’s face (at 3:23) as Jaki grunts his way through a solo that displays his patented command of keyboard styles from stride to bebop to avant-garde.

Speaking of routes, one of the most impressive of Byard’s compositions is “European Episode,” which he recorded with tenor saxophonist Booker Ervin and trumpeter Richard Williams in 1964 on Out Front! The work was composed as a dance suite in six parts inspired by a European sojourn that wound its way from Brussels to Paris to Milan. Jaki’s boyhood friend Don Asher, who wrote of the transforming influence Byard had on his young life in his superb memoir Notes From a Battered Grand, describes “European Episode” as “kaleidescopic…a hurly burly of urban streets in a lively excursion of shifting tempos, rhythms, and evocations.”

In Notes From A Battered Grand, Asher says he first encountered Jaki at Dominic’s Cafe, a “bucket of blood” on Worcester’s east side. He recalled Byard as a “a big heavy-shouldered fellow in blue shirt and brown pants. His eyes seemed remote, inwardly focused as he played, and his smooth, plump, sweating face glistened with ardor and tension.” In due time, he persuaded Jaki to give him lessons, of which Asher wrote, “Every Friday afternoon I went straight from high school to Jaki Byard’s house on Carroll Street. I arrived at 1:30, and when I left the shadows were lengthening…If members of his family needed the parlor, we’d go down the street to the Saxtrum Club, a converted store that was a place to hang out and jam for Central Massachusetts musicians and road bands coming through…Roy Eldridge dropped by, and Anita O’Day, Gene Krupa, Cozy Cole, Frank Sinatra. Jaki, at 18, was the club’s resident luminary and official host. On nights when there were no sessions at the Saxtrum, he would lock the door early from the inside…and he’d practice on the ancient upright all night—scales and exercises…random excursions and improvisations mingling with snatches of Bach and Chopin. If he knew there was someone listening outside the door—and before midnight there was often a knot of us, like kids huddled around a bakery shop drawn by the rumor that free samples might be given out—he’d slide into some whomping, way-back whorehouse piano, a big, pumping, joyous sound, and in our imaginations it was like being present at a spectacular parade, hearing a whole history of the music from the New Orleans cribs and levees on up the river.”

Byard returned to Boston in 1969 at Gunther Schuller’s request to establish the Afro-American Music department (now Jazz Studies) at NEC, and he also taught at the Hartt School at the University of Hartford, the New School, and the Manhattan School of Music. Among the well-known musicians who credit Byard as a teacher and mentor are Ricky Ford, Marty Ehrlich, Jason Moran, and Alan Pasqua. 18 years after his death, Byard’s legacy remains significant and cherished at NEC. In a note to Jaki’s daughter Diane on this YouTube clip of Byard’s performance at the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival, Pasqua writes, “Your father changed my life by encouraging me to move to Boston to study with him. When I got there, he was there for me, in every way. It was not lip service. He was my friend and mentor.” Pasqua has been in the news this month as the pianist who accompanied Bob Dylan on his Nobel Prize speech. Read a New York Times feature on Alan here. In a comment for this article, Marty Ehrlich said, “The man was touched by genius. Musicians all knew it…He was not cut out to conquer the world. We are all the beneficiaries of his generosity and brilliance.”

Pianist Jason Moran, who succeeded Billy Taylor as the advisor for jazz at the Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, spoke last month about the four years he spent as Jaki’s student at the Manhattan School of Music.

The late George Russell, another legend among NEC faculty, offered this knowing appreciation of his colleague. “Jaki Byard always personified the past, present and future of jazz, wherever or whenever one might have been fortunate enough to experience his challenging ideas. An icon in the history of jazz, Jaki was Art Tatum, Earl Hines, Bud Powell, Ran Blake, Cecil Taylor, and Bill Evans, all in one. Yet, like these fellow icons, he was his own uncompromising, unique, living entity. He isn’t a household name, but most likely his low profile is the result of an irresistible need to constantly reinvent himself, the sure sign of the consummate artist. His history, from Boston’s Storyville to the countdown year of the millennium, leaves us with a rich history of his music, his life and times, allowing us to experience the intense struggle of a dedicated artist to keep his essence alive while still making us laugh with him along life’s corridor. There will never be anyone who can take his place.”

Byard is the subject of a film directed in 1979 by Harvard student Dan Algrant. Anything For Jazz includes Ron Carter and Bill Evans speculating on why Byard isn’t better known, and footage from Ali’s Alley in New York and Michael’s Pub. Jaki plays Charles Mingus’s “Fables of Faubus,” and conducts the Apollo Stompers in a performance of “I May Be Wrong (But I Think You’re Wonderful).” Home movie footage of Jaki’s family walking along a beach is seen while he plays a new composition dedicated to his mother, mother-in-law, and newly born grandson. If you look closely, you can also read the fine print on Western Union telegrams from Earl Bostic and Billy Eckstine requesting Jaki’s services. And the film concludes with a reflection that could only have been made by an artist who understand what mattered most. “I tell my students they’ll never be a success if they write like me, but you’ll be a success for yourself.”