Joe Beard

Rochester’s Mississippi Bluesman

I first heard about the bluesman Joe Beard nearly 40 years ago, right around the time that Johnny Copeland was emerging as a too-good-to-be-true blues master largely unknown outside of Houston. Beard was little-known too, but reports began circulating in the seventies that there was a guitarist playing blues, “as deep as it gets,” in Duke Robillard’s recollection, around Rochester, New York. Robillard recalled this week that he first met Beard when Roomful of Blues, the band he established in Providence in 1968, began playing Rochester. “One of our first regular stops was at the Red Creek Inn in Rochester. We’d play there and then move on to Buffalo and Toronto. Joe would come to see us and we met. Then he sat in with us, and he knocked us out. He was the real deal. Mississippi blues in Rochester. And he was a true gentleman to boot.”

As word got around, a few of my friends made the trek upstate to see him at local clubs, but I knew Beard only as a rumor until Robillard and fellow New England guitar legend Ronnie Earl recorded albums with him in the nineties. Duke played on the Audioquest releases For Real in 1998 and Dealin’ in 2000, and says it was keyboard player Bruce Katz who “put those bands together, and he brought me in as a sideman for two albums. Working with Joe was a piece of cake. One, two, three, go. There it is. Joe did most all of it in one take.”

While the records attested to Beard’s excellence and “real deal” authenticity, I didn’t get a chance to see him in person until last summer’s Son House Festival in Rochester. There he played his devastating slow blues, “No More Cherry Rose”, and few other tunes that roused the packed house at one of the festival’s evening concerts headlined by John Mooney. The following afternoon, he attended the dedication of a Mississippi Blues Commission marker to Son House. His presence offered a living reminder of the late-career significance of House and the lineage of the Delta blues. He and Son were Mississippians of different generations who’d migrated to Rochester, House arriving in 1943, Beard in 1957. In a remarkable example of small-world synchronicity, in the spring of 1964, Beard, who’s an electrician, became the superintendent of the apartment building where House resided at 67 Greig Street in Rochester’s Corn Hill neighborhood. Joe and his wife Mary lived with their family of four children three doors down at 61 Greig, and at night as he strummed his guitar and sang the blues in his warm tenor voice on the building’s front porch, Son heard him, and he asked for more.

In Daniel Beaumont’s biography, Preachin’ the Blues: The Life & Times of Son House, Beard said, “Son loved to hear me do the acoustic thing alone. He would sit in my living room, and just ask me to do certain things that he loved to hear…There’s a thing that I play on the guitar that Nathan Beauregard used to do, and he loved that…The song was called ‘Mellow Peaches’.” Reflecting on his initial meeting with the Delta blues legend, Beard said, “I had really never heard of Son House. I’d never listened to him or Charley Patton. I knew of Robert Johnson, but I didn’t know he was associated with Son House. But then Son told me all these stories about him and Robert Johnson and Charley Patton.” Revealing a mark of the “true gentleman” that Robillard observed, Joe added, “You know, I never was one to say, ‘He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.’ I never [question] a person that way.”

By 1964, House hadn’t played or owned a guitar in years, maybe as many as 15, and notwithstanding his early brilliance and direct influence on Robert Johnson and Muddy Waters, he’d spent his entire life haunted by the notion of blues as the forbidden devil’s music. Beard played a significant role in rekindling Son’s smoldering blues flame, and the timing was perfect. For just a few weeks later, House became one of the most treasured finds of the blues revival when three young blues enthusiasts, Nick Perls, Phil Spiro, and Dick Waterman, who’d searched the Deep South for him before getting a tip that he lived in Rochester, knocked at his door on June 21, 1964. With a little prodding, Eddie James “Son” House, Jr soon returned to form as one of the greatest bluesmen of all time, and he spent the next decade playing gigs and making a handful of stirring albums that compare favorably with his Paramount recordings of 1930 and Library of Congress sessions in 1941-42.

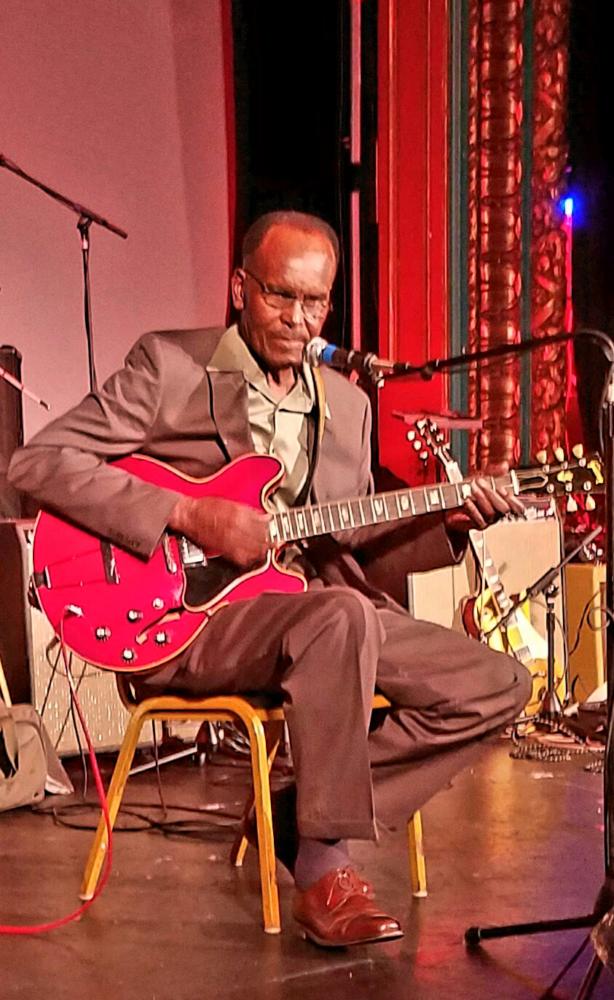

Joe Beard is one of the last of the generation of blues players born after 1930 whose path wound from Mississippi to Memphis to Chicago and beyond. Now in his mid-seventies, his tall, lean frame enhances a healthy and youthful appearance, and his stoical mien and unforced singing belie the intensity of his blues. Joe was born in Ashland, Mississippi, and raised in nearby Olive Branch where in his youth he served as a lead boy for the blind singer and guitarist Nathan Beauregard. He counted among his closest boyhood friends Floyd and Matt Murphy; Floyd played guitar on Junior Parker’s classic recordings, “Feelin’ Good” and “Mystery Train,” and Matt’s career as a guitarist included stints with Memphis Slim, James Cotton, and the Blues Brothers. Beard’s career has had fewer celebrated distinctions, but he’s the equal of anyone playing blues today.

Last summer’s Son House Festival was duly recognized by the city of Rochester as a major event, and the Geva Theater Center, the festival’s host site, honored his legacy in impressive fashion. The New York Times published this feature story on Keith Glover’s play Revival: The Resurrection of Son House, which was given a dramatic reading at the festival, and Rochester television station WXXI broadcast this in-depth feature on Son and Joe Beard.

Joe was at the Regent Theatre Arlington on Saturday for the 8th annual Blues After Hours concert in memory of WGBH radio host Mai Cramer. There he played two solo numbers and a handful of tunes backed by Peter Hi-Fi Ward, Anthony Geraci, Bob Berry, and George Dellomo. Here he is in 2010 playing “Little By Little,” which he also played on Saturday.