Making the Impossible Look Easy

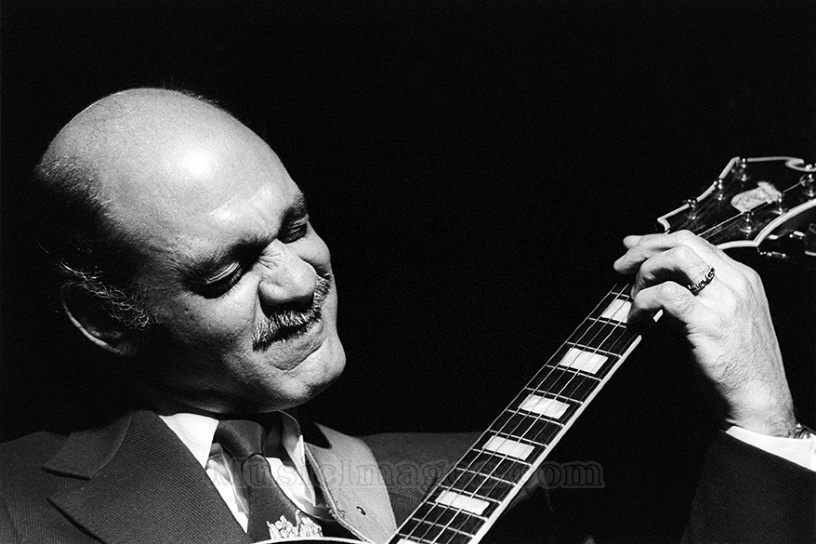

Today is the 87th birthday anniversary of Joe Pass. The virtuoso guitarist was born Joseph Anthony Jacobi Passalaqua in New Brunswick, NJ on January 13, 1929, and died in Los Angeles on May 23, 1994, at 65. Pass was an underground legend until he was in his mid-forties. Initially inspired by the “Singing Cowboy,” Gene Autry, and encouraged by his father, a mill worker in Johnstown, PA, who recognized his son’s precocious musical talent as an avenue out of the Rust Belt, Pass began playing professionally at the age of 14, and eventually toured with the bands of Tony Pastor, Charlie Barnet, and Ray McKinley.

Pass settled in New York in the late forties and spent nights at the Royal Roost listening to Charlie Parker and playing jam sessions around town. But heroin addiction, the scourge of modern jazz in the post-war years, claimed him, and he spent over a decade chasing a fix and looking for gigs. He lived for a time in New Orleans, where he played for strippers and resided in a building that housed saxophonist Brew Moore and William Burroughs, who’d just published his 1953 debut novel, Junkie. Pass next worked in show bands in Las Vegas, where he got busted for possession of marijuana in 1954 and sentenced to the federal narcotics prison in Fort Worth, Texas. Upon release four years later, he returned to work in Vegas and in Southern California, but still hampered by dope, he entered Synanon in 1960.

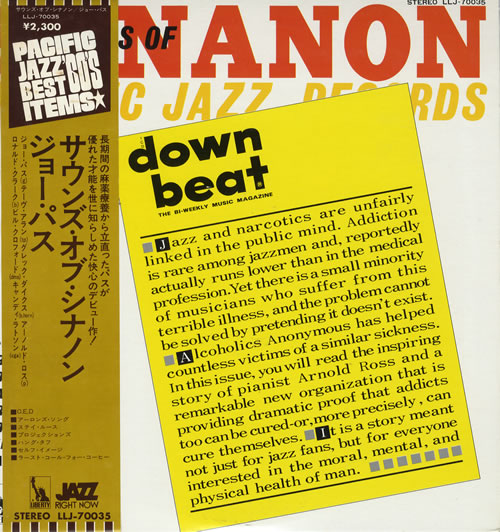

A year later, Pacific Jazz released the album Sounds of Synanon, which featured Pass and fellow residents of the pioneering rehab facility in Santa Monica. Leonard Feather reviewed the album for the July 5, 1962 issue of Downbeat and said, “This album does more than merely present a group of good musicians, it unveils a star. In Joe Pass, Synanon and Pacific Jazz have discovered a major jazz talent.”

Pass remained at Synanon until 1963. For the next decade, he worked as a studio musician around Los Angeles; earned the praise of Wes Montgomery; and recorded with Gerald Wilson’s Orchestra. He’s featured on two of Wilson’s masterful Pacific Jazz albums, Moment of Truth and Portraits. From the latter, recorded on December 2, 1963, Pass plays acoustic guitar on Wilson’s arrangement of “‘Round Midnight.” Harold Land is the tenor saxophone soloist.

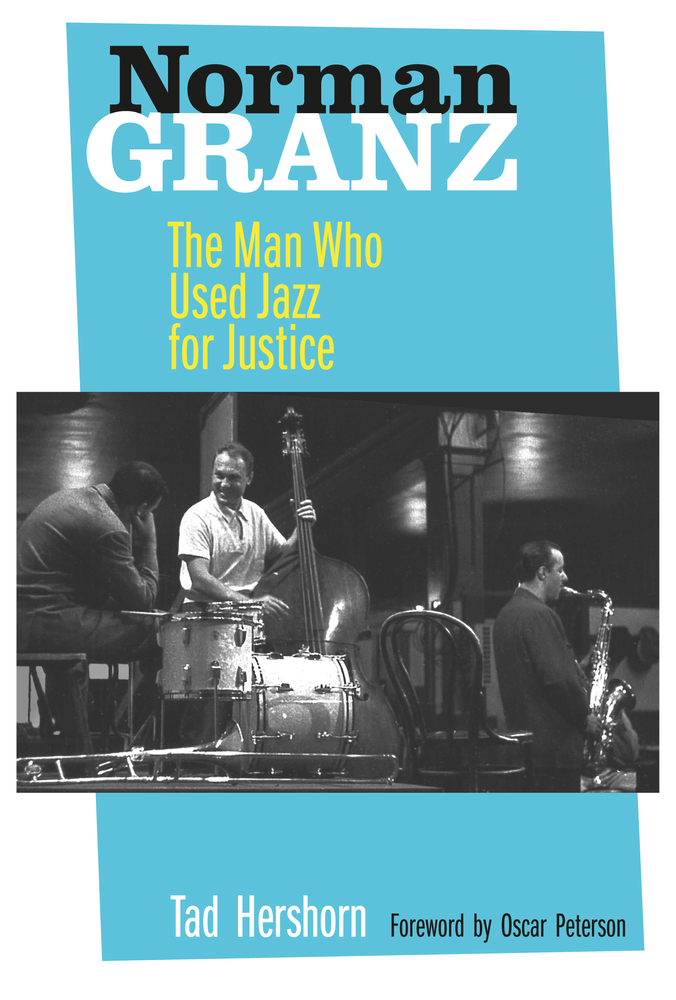

On June 2, 1972, Pass attended a now-famous concert at the Santa Monica Civic Center starring Ella Fitzgerald and Count Basie. It was presented by Norman Granz, and also featured Roy Eldridge, Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis, and Joe’s friend, Stan Getz. Granz was only vaguely familiar with Pass at the time, but the buzz backstage about the guitarist prompted him and Oscar Peterson to check out the guitarist the following night at Donta’s in Hollywood, where Joe was appearing with Oscar’s former sideman, Herb Ellis. Granz’s biographer Tad Hershorn says Granz and Peterson were “equally awed by Pass’s command of his instrument and the precision with which, as a solo guitarist, he used single notes to convey chords, bass, and melody in ways that emulated saxophone solo lines and piano accompaniment.” In a later interview with Hershorn, Peterson said he was impressed by Pass’s “invention. The way he sat up and improvised, and it just rolled out of him. But lyrically, Joe had such a sense of invention with the ballads. Norm knew without saying anything what Joe stood for and who Joe was.”

Thirteen years earlier, in 1959, Granz had left Los Angeles and moved to Switzerland, and the following year he’d sold Verve Records, the jazz label with which his name remains synonymous. He spent the next decade amassing a sizable collection of modern art that included works by his friend Pablo Picasso. That same decade saw a tumult in the music world brought on by the soaring popularity of rock and, on a smaller scale, the marginalization of straight-ahead jazz as free jazz and fusion dominated the jazz press and record business. In 1971, Granz told Leonard Feather, “It’s a disgrace what the jazz artists of today are being forced to do, recording material that is all wrong for them. It’s criminal, too, that someone like Sarah Vaughan was allowed to go without making a single record for five years…Record…executives today are only concerned with the fact that they can gross $9 million with the Rolling Stones. They forget that a profit is still a profit, and you’re still making money if you only net $9 thousand. I keep telling people that, and they think I’m crazy.”

The Santa Monica concert was a prelude to Granz getting back in the business. In 1973, he established Pablo Records, the same year that another Californian, Carl Jefferson, established Concord Jazz. The immediate success of both labels signaled that a substantial audience was still eager to hear music played by established and emerging players of mainstream jazz. Like Verve, Pablo reflected Granz’s personal tastes and his ongoing devotion to Ella, Oscar, Basie, Sarah, and Roy, as well as Milt Jackson, Harry “Sweets” Edison, and Zoot Sims. To the delight of Sims fans, the saxophonist’s discography mushroomed under the Pablo banner and now stands as a significant part of his legacy.

But it was Pass who was the least renowned of these artists when he signed with Granz, and the association brought him a first and lasting brush with popular and critical acclaim. Like his touring concert package, Jazz at the Philharmonic, Granz utilized the stable of artists under contract to him as interchangeable parts, and Pass fit in with virtually everyone at Pablo, appearing as a sidemen with the label’s stars and leading solo and small combo recordings of his own. Joe’s first date at Pablo came as a complete surprise when he was brought in to play on a session with Duke Ellington. Duke’s Big 4, recorded on January 8, 1973, was one of the bandleader’s final dates and his only album featuring a guitarist in a solo role. It kicks off with “Cottontail.”

Pass then joined the dynamic duo of Peterson and bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen and went on to tour and record extensively with them for nearly two decades. Their sensational debut, The Trio, was recorded live at the London House in Chicago in May 1973.

Ellington’s spiritual theme, “Come Sunday,” was Joe’s solo feature at the London House and it remained a staple of his repertoire with Peterson and Pedersen. Here he plays it in Tokyo in 1987.

A memorial tribute to Ellington was the focus of Joe’s first album as a leader for Pablo. Portraits of Duke Ellington was recorded less than a month after Duke’s death in May 1974. I’ve long found it hard to select just one tune from the record for airplay in Jazz a la Mode, so for now let’s go with the album’s opener, “Satin Doll.” Equal credit for this gem goes to bassist Ray Brown and drummer Bobby Durham.

A month after Joe’s debut with the Peterson trio, he and Ella Fitzgerald appeared together at Carnegie Hall for that year’s Newport-in-New York Jazz Festival. The performance was so well-received and agreeable to the principals that they recorded a duo album, Take Love Easy, the following month. Pass told Ella’s biographer Stuart Nicholson, “The first album I did with her, we went into a studio and Norman Granz brought a bunch of tunes in, lead sheets, songs. I had no idea whether she’d want to rehearse or what keys she sang in. But she just picked a tune like ‘Gee Baby, Ain’t I Good to You.’ I said, ‘What key?’ She said, ‘Well…’ and just sort of hummed a little bit. I found the key, and we just did a whole album like that…I could change keys with her, anything I wanted to do. She’s just there, she hears it, no problem! It’s like another musician…sort of like a horn player.”

Downbeat’s review of Take Love Easy praised Pass for solos that are “intricate but not flashy. A thoroughly disciplined musician, he never tries to upstage her.” Ella and Joe’s complete concert at Hannover, Germany in 1975 circulates on YouTube. From it, here’s the First Lady of Song lauding Joe and introducing what she calls a “torchy song,” the Julie London classic, “Cry Me a River.”

An Evening With Joe Pass was produced in 1994. It combines a solo performance with Joe’s reflections on the state of the art of both accompaniment and solo jazz guitar. When it was first proposed in 1974, Pass was dubious of the idea of performing solo, but Granz proved to be persuasive. Hershorn’s biography reports that when Pass expressed skepticism, Granz said, “Piano players do it. Segovia does it.” Pass countered that Segovia is “a classical player,” but Granz persisted. What followed was Virtuoso, Joe’s second album for Pablo. It was the first of many solo sessions he made for the label, and one that elicited from Downbeat an observation about Pass that applies to virtually everything he ever played. “If one definition of genius is that it can make the impossible look easy, Pass certainly qualifies on this count alone.”