Horace Silver says that his father was “greatly offended” the first time he saw the term “funky” applied to his son in Downbeat. “What do they mean, you’re funky. You take a bath every day.” Horace adds, “He didn’t know the jazz meaning of the word.”

Lester Young, whom Silver played with in the early ‘50’s, also objected to the term when Norman Granz asked him to make a “funky introduction” on a take of “Two to Tango.” “You said, ‘some funky introduction’,” queried a bemused Pres. When Granz shrugs him off, Pres says, “There’s ladies out here.” Hear it for yourself at 2:30, complete with accompaniment by Oscar Peterson. It’s Lester’s only singing on record.

About 20 years ago, this writer was asked by Merriam-Webster to advise on an updated definition of funky. What I gave them is hinted at in the second meaning they give the word, but I disagree with their adjectival use of “unsophisticated” to describe the method and effect of funk. Maybe it’s not meant as a pejorative, but M-W defines unsophisticated as “not having or showing a lot of experience and knowledge about the world and about culture, art, literature, etc.” For me, that’s an antiquated notion of the vernacular in general, and of what we’ve come to appreciate about the timeless truths and felicities of blues and jazz. Whatever their intent, if you were to explore M-W’s citation file for something “having an earthy unsophisticated style and feeling; having the style and feeling of older black American music,” i.e., funky, you’ll see my name.

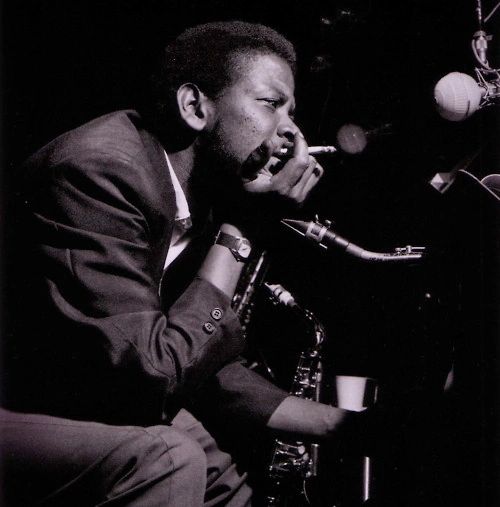

Junior Cook excelled at playing Silver’s brand of funk. The tenor saxophonist, who was born Herman Cook 80 years ago today in Pensacola, Florida, was a member of the iconic Horace Silver Quintet that was together between 1958 and ’64. Of this combo, the late pianist said, “One thing I liked about the Blue Mitchell-Junior Cook band was that they could play bebop and they could play funky. Some musicians in those days excelled at bebop but couldn’t play funky. Other musicians excelled at playing funky but couldn’t play bebop. [They] played well in both idioms.”

Here’s a good example of what Silver means in this performance of “Senor Blues” at the 1958 Newport Jazz Festival. Horace often introduced the piece as “a lowdown, bluesy type composition, a minor blues written in 6/8 time. This is a blues with a Latin beat added to it.” The funk walks the walk.

The Newport performance, which Blue Note released a decade ago, is as good as it gets, but here’s a better print of “Senor Blues” with effective close-ups of Cook, Blue Mitchell, Gene Taylor, and Louis Hayes.” Given the almost complete lack of response from the audience, I would guess this was filmed in Europe.

From the same European venue, here’s the quintet displaying its bebop chops on Silver’s “Cool Eyes.”

After his six-year tenure with Silver came to an end, Cook spent another five in the quintet that Blue Mitchell led through 1969. It was essentially the same Silver quintet with a run of pianists that included Chick Corea and Ronnie Mathews. When it disbanded, Cook spent a year teaching at Berklee, and then spent several years cookin’ with Freddie Hubbard. He also co-led quintets with Louis Hayes and trumpeter Bill Hardman, and spent his last years as a journeyman player on the New York scene. Over the years, he made a handful of outstanding recordings as a leader, including a 1981 session, Somethin’s Cookin’, with Cedar Walton, Buster Williams, and Billy Higgins that crackles with fire, and a trio of excellent releases for Steeplechase in the late 80’s including The Place to Be, notable for the brilliant playing of the under-recorded pianist Mickey Tucker.

Here’s Junior with Bill Hardman, pianist Walter Bishop, Jr., and drummer Leroy Williams playing his former associate Corea’s original, “Spain.”

I saw Cook with both Hardman and Hubbard on a few occasions in New York and Boston in the ’70’s; first time out, it was with Hubbard at the jazz fest George Wein produced at Fenway Park in 1972, a kind of makegood for the disastrous festival of the previous summer at Newport. It wouldn’t be my last association of Junior with baseball, for the last time I caught him was on October 15, 1988, at The Network in Springfield, where he led a quartet featuring Tucker, Nat Reeves, and Steve McCraven. The date was made doubly unforgettable by virtue of the Dodgers-Athletics World Series game being played that night in Los Angeles. It was Game One of the ’88 Series, the one renowned for Kirk Gibson’s walk off homer against Dennis Eckersley. Vince Scully said that calling on the badly hobbled Gibson to pinch hit was “a roll of the dice;” this was his only plate appearance in the series, which the Dodgers won, 4-1. Seven years later, it was voted the greatest moment in L.A. sports history. Of the 50 players who made up the two squads, Eckersley is the only one who’s been elected to the Hall of Fame (both managers, Tommy LaSorda and Tony LaRussa, are members too), but it was Gibson who prevailed that night. We watched it at The Network, but what we heard was Junior Cook wailing on tenor. Here’s the complete at-bat as called by Vince Scully.