(Buck Clayton, 37th Army Service Band, 1945)

(Buck Clayton, 37th Army Service Band, 1945)I chose the picture of Buck Clayton and Lennie Sogoloff to go with yesterday’s blog because I’ve been listening to Buck all week. Tomorrow is the centennial of the trumpeter’s birth, and we’ll celebrate with his music in tonight’s Jazz a la Mode. Tune in at 8 to hear Clayton’s smooth cup-mute and open horn on recordings with Count Basie and many more. Buck came to prominence with Basie after the bandleader persuaded him to replace Hot Lips Page in Basie’s fledgling outfit when it was still only a local phenomenon at Kansas City’s Reno Club. Buck, who grew up in Parsons, Kansas, had been around the block by then, working in Los Angeles after high school, then leading a band he called the Harlem Gentlemen in Shanghai. But Basie snared him upon his return in ’35. Even then, “Basie could swing you into bad health,” Clayton recalled in his memoir Buck Clayton’s Jazz World.

Clayton’s art was forged in an era when players thought in terms of 8, 16 and 32 bar statements, and Buck’s brief solos with Basie and his darting obbligatos behind Billie Holiday and Jimmy Rushing are among the most melodic of the age. His opening chorus on “Goin’ to Chicago Blues” was later lyricized by Jon Hendricks and became as integral to the tune as Rushing’s original. Annie Ross sang a lyric to Clayton’s “Fiesta in Blue” which Buck described as “unbelievable, she did my solo word for word, or note for note.”

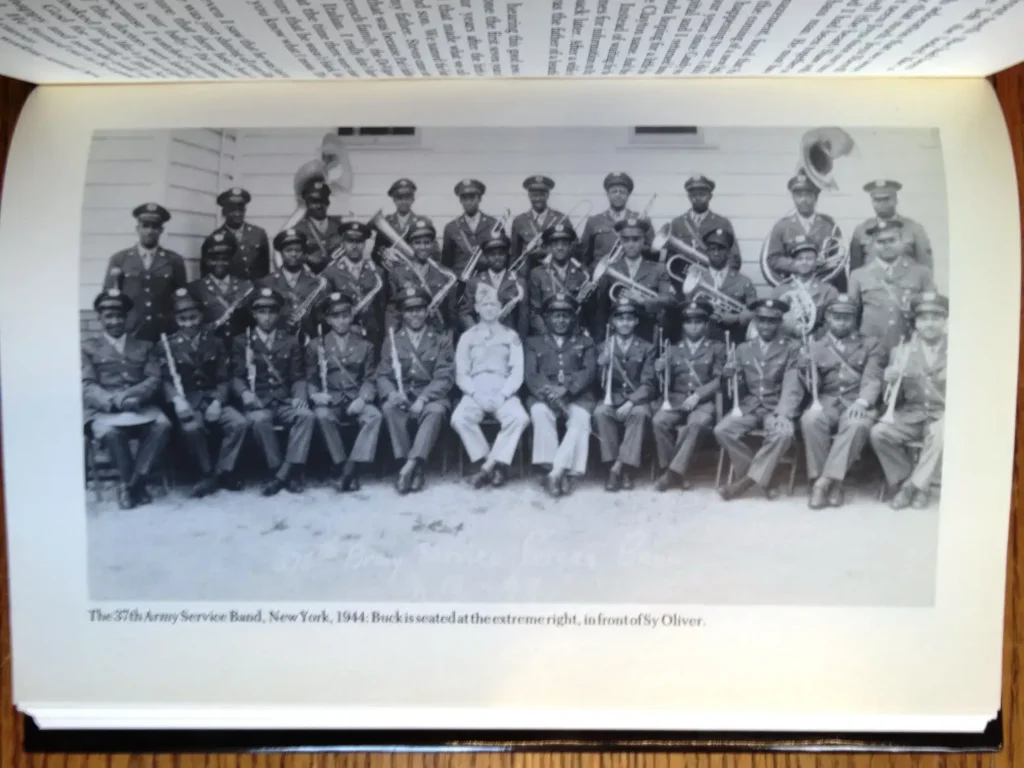

Clayton served in the 37thArmy Service Band during World War II, and upon discharge freelanced around New York, appearing on dozens of small group swing sessions during a golden age for that glorious idiom. Clayton was on the first national tour of Jazz at the Philharmonic where he shared the stage with Charlie Parker and Coleman Hawkins. In the mid-50’s, he led a series of in-studio jam sessions that featured players who’d come to prominence during the Swing Era. John Hammond produced these recordings, and the English-born jazz chronicler Stanley Dance coined the term “mainstream jazz” to describe them. It’s a stream we love to plumb the depths of in JALM.

Buck worked at The Embers, a show biz haunt, for several years in the mid-1950’s, and often connected with his fellow Basie-ite Buddy Tate for recordings and tours. But lip problems, the bane of brassmen, began to plague Clayton in the late 60’s, and he eventually stopped playing in 1979. He found a second career in his later years teaching at Hunter College, and composed and arranged a substantial body of tunes. The first of these, “Love Jumped Out,” was recorded by Basie in 1941, and his tunes form the base for The Buck Clayton Legacy and other repertory bands featuring Randy Sandke, Harry Allen, Howard Alden, and others devoted to his music.

There’s another parallel between Clayton and yesterday’s Lennie’s-on-the-Turnpike post: Buck left a substantial archive to the University of Missouri at Kansas City which contains hundreds of photographs among other memorabilia. Click here for the archive. Or try here for direct access to an amazingly comprehensive look at the long life of Wilbur “Buck” Clayton.

For a taste of Buck in person, here’s footage of his All-Stars featuring a great tenor solo by Buddy Tate on “Outer Drive.” We’ll hear this same group tonight playing “Swingin’ at the Copper Rail.”

*****

As it happens, tonight’s show is a two-for-one, as we’ll hear another Kansas City jazz great, Dick Wilson, whose 100thbirthday anniversary is today. Wilson was the tenor saxophone star of Andy Kirk’s 12 Clouds of Joy, but he died in 1941 at age 30 and his legacy is limited to a small body of recordings with Kirk and a session led by Kirk’s great pianist-arranger, Mary Lou Williams. Wilson is largely forgotten now, but he was a principle combatant in the tenor battles that form part of the lore of Kansas City jazz, and notwithstanding his big, Coleman Hawkins-like tone, he was the first tenor player to reflect the influence of Lester Young’s rhythmic conception. Listen tonight for Wilson’s feature on “In the Groove” and you’ll hear the kind of phrasing that Young introduced on “Tickle Toe” and dozens of other sides.