In Concert with the Jazz Messengers

Lee Morgan and Wayne Shorter, two of the most incisive and arresting soloists in modern jazz, made for one of the greatest trumpet/saxophone front lines in the music’s history. Morgan was an established, new-star 20-year-old, hailed by the Pittsburgh Courier as “one of the toughest of the tough,” when he joined Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers in 1958. Together with fellow Philadelphians Benny Golson, Bobby Timmons, and Jymie Merritt, he helped define a bold new Messengers sound on the band’s Blue Note release, Moanin’. The album was paced by Golson’s writing and arrangements, and Timmons’ title composition, which remains one of the high watermarks of soul jazz, helped make the album the biggest seller of Blakey’s career.

Notwithstanding the quintet’s great sound and immediate success, Golson moved on and co-founded the Jazztet with Art Farmer after a year with Blakey. But while his tenure was brief, he brought a new level of professionalism to the group and helped raise the quality of its nightclub and festival bookings. In his excellent new memoir, Whisper Not, Golson writes, “Moanin’ was a hit. We heard it on jukeboxes wherever we went. In droves, people were becoming aware of Art Blakey and The Jazz Messengers. Increased fees were now a solid index of our mounting popularity. Art no longer questioned anything I said.”

Hank Mobley, who’d been a charter member of the Messengers when the group coalesced around Blakey and Horace Silver in 1954, succeeded Golson. The tenor saxophonist returned to the fold as music director with a sheaf of new compositions that included “Just Coolin’,” and “Hipsippy Blues.” But he also came with a worsening heroin habit that soon made him unreliable. When he failed to appear for a performance at the first annual Canadian Jazz Festival in Toronto in June 1959, Blakey and Morgan immediately began courting Shorter, who was there with Maynard Ferguson’s big band. Shorter and Morgan already relished the idea of working with each other, so when Lee broached the topic Wayne agreed to meet with Blakey on the festival grounds. The drummer simply asked, “Do you have eyes?” Shorter gave Ferguson two weeks notice that night, then made his debut as a Messenger in July at the French Lick Jazz Festival in Indiana.

Lee and Wayne meshed beautifully, and Shorter proved to be a stimulus to Morgan’s development as a composer. It was Wayne’s prolific output, however, that dominated the Messengers book and brought him to prominence. They recorded together for the first time on VeeJay Records with Wynton Kelly, and led sessions of their own for the Chicago-based label beginning with Wayne’s debut as a leader, Introducing Wayne Shorter. (Morgan had already recorded what he would later call too much material for Blue Note beginning at age 18.) Their first date with Blakey was in November 1959 on Africaine, which went unreleased at the time, but in a span of just 18 months, they appeared on eight brilliant studio albums including The Big Beat, Like Someone in Love, A Night in Tunisia, Roots & Herbs, The Freedom Rider, The Witch Doctor, À la Mode, as well as the two-volume release from Birdland, Meet You at the Jazz Corner of the World. Numerous club and concert bootlegs subsequently surfaced from this period.

Morgan had been using heroin for several years before the ravages of the addiction caused him to begin missing gigs and showing a lack of interest in the music. The handwriting was on the wall when he announced that he was leaving Blakey in August 1961 to form his own band, a band that never fully materialized. Instead, the 23-year-old trumpet sensation returned to Philadelphia so broke that he pawned his horn and boarded with his sister’s family, then with his parents. He went for long periods without playing gigs, and for a brief period co-led a Philly-based quintet with Jimmy Heath that played well-received dates in Washington, D.C. and New York. His descent continued into 1963, and rumors of his death were so widespread that Symphony Sid broadcast a memorial tribute to him. In November 1963, he enrolled in the heroin detox program at the Federal Narcotics Treatment Hospital in Lexington, Kentucky. Dorothy Kilgallen’s New York society column stated, “Lee Morgan the talented young trumpeter, has gone to Lexington for the cure.”

A month later, with a new, three-album contract with Blue Note in hand, Morgan entered Rudy Van Gelder’s studio to record The Sidewinder, the soul jazz classic that became the most successful album of his career. Joe Henderson played tenor on the date, and on its follow-up, The Rumproller, but Morgan and Shorter began recording again the following year on Wayne’s Blue Note debut, Night Dreamer, and on Morgan’s most compositionally adventurous album, Search for the New Land.

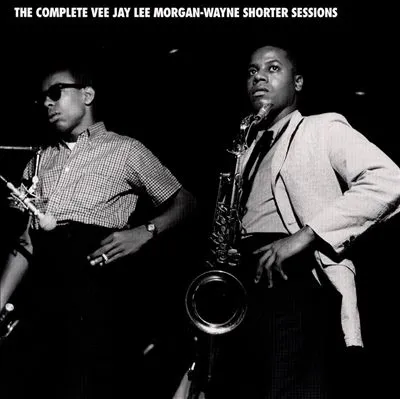

Yesterday was Morgan’s 78th birthday anniversary. The Philadelphia native is seen here with the Jazz Messengers in Tokyo in January 1961. There’s hardly a moment in this 48 minute studio performance that’s unessential, but one of its unique highlights is seeing Lee, Wayne, and Bobby Timmons doubling as percussionists while Blakey and bassist Jymie Merritt introduce “A Night in Tunisia.” It begins at 14:22.

The set of six tunes includes “The Summit” by Wayne Shorter; “Dat Dere” by Timmons;” “A Night In Tunisia” by Dizzy Gillespie; “Yama” by Lee Morgan; “Moanin’” by Bobby Timmons; and “Blues March” by Benny Golson.