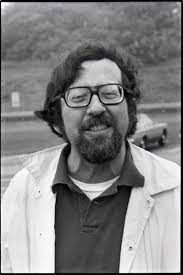

Lennie Sogoloff died today on Boston’s North Shore at the age of 90. He was the proprietor of Lennie’s-on-the-Turnpike, a hallowed jazz club on Route 1 in West Peabody, Massachusetts, which Lennie operated between 1951 and ’71. Sogoloff, who worked for Mercury Records at the time, originally provided a juke box stocked with jazz, then began presenting the living artists themselves. For a decade-plus, Lennie’s was on the itinerary of just about every jazz artist of the time. Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespie, and countless others played the room, and because Lennie was a straight-shooter and a “loving host,” as Cambridge record store proprietor Jack Woker put it, they kept coming back. When he added fifty seats to the club in 1964, his ads read, “Still warm and intimate.”

In my teens, friends and I traveled to Lennie’s on several occasions to see blues greats Muddy Waters, James Cotton, and Charlie Musselwhite, whose group included guitar legend Fenton Robinson. Lennie’s is where I first heard Clark Terry and Zoot Sims. Sogoloff’s gregarious manner helped foster a close rapport with performers, many of whom impressed us with their accessibility off-stage. One especially memorable experience was sitting with the Mississippi-born Musselwhite while he ate what he told us was his first lobster. But no matter who was performing, we were always struck by our proximity to the players, and how much more lifelike they seemed than the rock stars of our generation playing on distant stages in arenas and gymnasiums. (The Jazz Workshop in Boston, whose proprietor Fred Taylor still books Scullers, offered more of the same intimacy.)

When Lennie’s was destroyed by fire in 1971, Sogoloff continued to present jazz in settings north of Boston, but he worked primarily as a clothing salesman in Salem. Imagine the challenge he faced finding as much style in Hickey-Freeman as he did in Basie, Buck, and Byard. I would later see him at Boston and Cambridge nightclubs where he was invariably brimming with enthusiasm over whomever was on stage. I last saw him at a Duke Ellington symposium that I took part in at Salem State University a decade ago.

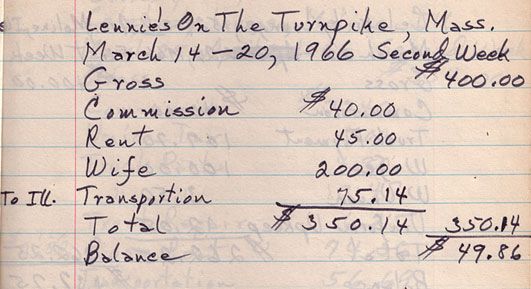

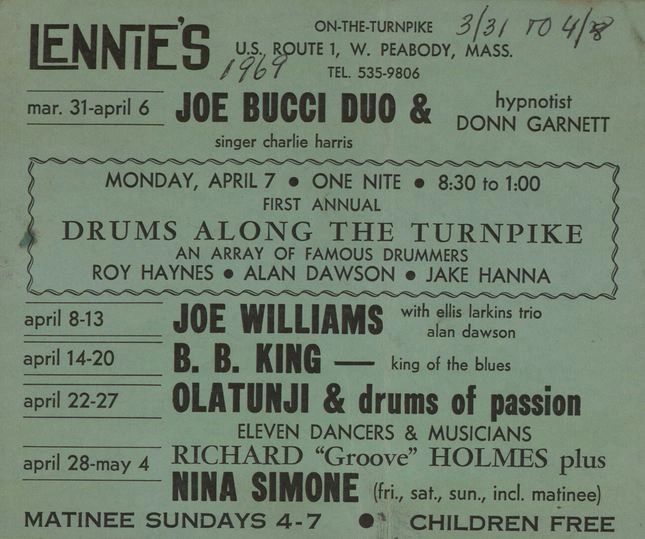

Worcester native Jaki Byard made recordings for Prestige at Lennie’s, and they’re among the most celebrated living artifacts from the club. That’s Joe Farrell, George Tucker, and Alan Dawson burning with Byard on “King David.” Argo released a lively set by Illinois Jacquet, Milt Buckner and Alan Dawson in 1964 that includes “Watermelon Man,” “On a Clear Day,” and “Illinois Flies Again.” Sogoloff presented this trio of audience favorites more than any other act besides Buddy Rich. How’s this for down home?

The documentary Mingus in Greenwich Village opens with footage shot at Lennie’s in 1966. Mingus, drummer Dannie Richmond, pianist Walter Bishop, Jr. and tenor saxophonist John Gilmore are seen playing “All the Things You Are” for the first 4:15 of Tom Reichman’s compelling film on the great bassist. Additional material featuring alto saxophonist Charles McPherson and trumpeter Lonnie Hillyer playing “Peggy’s Blue Skylight” and “Take the A Train” is interspersed throughout, and the band is seen arriving at Lennie’s at 34:25. (I wrote about Mingus in 2012 for Jazz Times. One of the comments on the article contains anecdotes about this appearance at Lennie’s. Read it here.)

There’s more to Lennie’s legacy. In 2006, Sogoloff donated his collection of memorabilia to Salem State University, and a selection of photos from the archive is available for viewing. Click here for this treasure trove of snapshots of dozens of jazz greats. Surprises include the legendary Earl Bostic in 1965; Abbey Lincoln modeling a stunning Afro in 1963; Jimmy Rushing at the microphone, and posing with Lennie before the Fisherman’s Memorial in Gloucester; Woody Herman’s band on Lennie’s cramped, low-ceiling stage; Howard McGhee relaxing with his beautiful wife; Jaki Byard playing tenor; Rahsaan Roland Kirk in action; and numerous place-cards naming the who’s who of jazz greats who’d be appearing soon.

The Boston Globe reported on Lennie when the collection and a scholarship in his name were established at Salem State. Sogoloff told the Globe that the relatively remote location of Lennie’s made it “a destination. You had to work to get here, but it was always a happy ending.” There’s more about Lennie’s on the website of Richard Vacca, author of The Boston Jazz Chronicles, an essential baedeker of the Boston jazz scene from 1937-1962.

Here’s Lennie himself recalling, “in a nutshell,” the glory days of the club. I had no idea until I watched this that the aforementioned Fred Taylor played a key role in the first presentation of a name act, Roy Eldridge, at the club. He also notes that “Berklee was a hotbed for talent” as he ticks off the names of Jimmy Mosher, Hal Galper, and Alan Dawson.

Memorial Services will be held at the Stanetsky-Hymanson Memorial Chapel, 10 Vinnin St., Salem, on Tuesday at 1:30 p.m. Burial will be private. A Celebration of his Life will be held following the service on Tuesday from 3-7 p.m. at the Frederick E. Berry Library & Learning Commons at Salem State University.