As filmmakers go, I probably knew the name Les Blank before anyone else besides Alfred Hitchcock. I would eventually become a devotee of Truffaut and Louis Malle and the American auteurs Scorsese and Altman and Woody Allen, but Blank’s documentary on Lightnin’ Hopkins was one of the first movies I ever watched that gave me a feel not only for its subject, but for its maker. The Blues Accordin’ to Lightnin’ Hopkins also gave me an eye-opening look at the tough, pistol-packing Texas blues culture that Hopkins embodied, and the secondary world of black cowboys and rodeo. Who knew? Thanks to the Worcester Public Library, which made its copy of the 16mm print available for circulation, I watched the movie numerous times with high school era friends who shared my passion for blues.

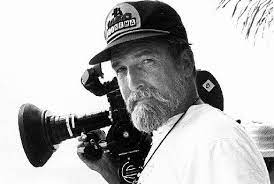

Les Blank died on Sunday at age 77. Here’s The New York Times obituary, which notes that Blank became interested in filmmaking after seeing Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. Where the Swedish director was a pioneer in bringing matters of the psyche, the unconscious, and religious faith to cinema, Blank was one of the first to illuminate how essential folk culture was to American identity and how endangered it was becoming. The Times called Blank the “filmmaker of America’s periphery.”

Les Blank’s first production was a 22-minute film on Dizzy Gillespie. Blank was a bugler in his youth but chose football over music when he left his native Tampa to attend Phillips Andover. There, he said, “I gravitated to the smoky, late night jazz clubs in New York and Boston, where I enjoyed abandoning whatever cares I had to the hot music, cold beer and wild women found therein.” He recalled that “a lot of serendipitous luck led to making Dizzy Gillespie in 1964.” Here’s an excerpt with Dizzy discussing the attacks and slurs that make for “a better buoyancy” in jazz. That’s James Moody on tenor saxophone.

Blank had a budget of $5,000 to work with when he approached Lightnin’ Hopkins in 1966. The great bluesman was working at the Ash Grove in Los Angeles, and true to his legend as a wary, no-nonsense performer who required payment before going onstage, he told Blank that five grand would be acceptable. When Blank told him the budget was for production costs and that documentary subjects usually weren’t compensated, Hopkins said “no thanks.” So Blank countered with an offer of $1,500, and Lightnin’ agreed. Years later, Blank said that he felt okay about paying him because Hopkins was “a professional musician, not [someone] doing it for YouTube.”

Born in 1935, Blank was among the earliest members of the white middle-class to find his identity in blues and to bring a personal, non-academic perspective to its documentation. He wrote, “Listening to the blues being performed by those who had truly lived the blues provided an escape from my problems and also gave me a strong sense of connection to pain and suffering, even though I had not been born into a world beleaguered by racism, poverty and gross injustice. I found that really listening to blues music provided a kind of comfort not experienced since my younger days as a believer in organized religion.”

Blank’s company, Flower Films, shot this footage of Hopkins relating the story of the stuttering boy who’s desperate to tell his adoptive “Mister Charlie” that his rolling mill is burning to the ground. Blank eschewed the voice of a narrator in most of his films and let his camera and subjects tell the story. In Hopkins, whom I recall hearing someone describe as the “poet of Houston’s Third Ward,” he had a veritable troubadour.

Blank became a devotee of New Orleans parade culture as an undergraduate at Tulane University in the mid ‘50’s. (He later studied filmmaking at USC.) The lively “second line” tradition of the parades, whether for ceremonial purposes like funerals and social functions hosted by clubs like the Zulu Aid & Social Pleasure Club, or what he saw as “spontaneous non-funeral parades [that] had no destination and no apparent purpose except immediate pleasure,” fascinated him and inspired him to jump on (and fall off of) floats in his hedonistic college days. In the early ‘70’s, Blank returned to the Crescent City to film Always for Pleasure, his look at the “fascinating street culture of New Orleans.”

Blank’s documentary subjects also included garlic, gap-toothed women, and the filmmaker Werner Herzog, about whom he made his best-known film, Burden of Dreams. But music was his primary calling, and in tandem with Chris Strachwitz, the German-born folklorist who founded Arhoolie Records 50 years ago and was profiled recently on NPR, Les explored Tex-Mex and other rural cultures. His 1973 documentary Hot Pepper focused on Zydeco music and includes rare footage on the great accordion-playing bluesman Clifton Chenier.

The Times obit concluded with a story about Blank’s receipt of the MacDowell Medal. “In 2007 Mr. Blank received the Edward MacDowell Medal, presented annually since 1960 by the MacDowell Colony in Peterborough, N.H., to an individual who has made an outstanding contribution to the arts. Its previous winners included Thornton Wilder, Robert Frost, Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein and only two film directors, the avant-gardist Stan Brakhage and the animator Chuck Jones. [Taylor] Hackford was the chairman of the jury, which included the directors Ken Burns, Steven Soderbergh, Mira Nair and Spike Jonze, as well as Thomas Luddy, a founder of the Telluride Film Festival.

“We all met in New York City, and I was expecting that we’d be discussing names like Francis [Ford Coppola], Marty [Scorsese], David Lynch and so on,” Mr. Luddy wrote in an e-mail. “Taylor Hackford spoke first and said we’d be talking about many of the obvious great names, but his candidate was Les Blank. He said that in 100 years his own films and many of the films by the big names may well be forgotten, but Les Blank’s films will be revered as time-capsule classics. I said ‘Amen,’ as did all the other members of the committee. We never even discussed another name, and our meeting was over in less than an hour.”

Last year, Blank was interviewed for the Los Angeles series BYOD (Bring Your Own Documentary), which you can see it its entirety here. In this excerpt, he discusses Always for Pleasure and his formative New Orleans sojourns. Les Blank, R.I.P.