While writing about Emerson earlier this week, I had occasion to include an excerpt of the interview I conducted with Harold Bloom in 2004. Alas, there’s reason to excerpt even more of our conversation with the news this afternoon of the death of Levon Helm. I heard from several readers who were surprised to learn that Bloom is a jazz fan, but here’s an exchange between us that I didn’t anticipate…

Reney: You mentioned Parker’s Mood earlier, Bird’s great blues. Do you like the blues as a vocal form, and do you appreciate the blues, at all, as poetry?

Bloom: Yes. Yes. To some degree, but I don’t know that, as poetry–it doesn’t often, anyway–let’s put it this way–it doesn’t often break through every final aesthetic barrier the way those earlier groups of Armstrong, the Hot Five and the Hot Seven and so on, and Parker and the gang in their prime, or that combination of Powell and Roach and Curley Russell…that seems to me, aesthetically, a touch beyond the poetry of the blues. At least, you know, any blues that I know.

And of course there’s that strange way–I’m not a great fan of rock’n’roll, as you might guess, especially in its horrible decline. In fact, the only rock’n’roll I can still listen to, because I liked them when they were around, and I still like to listen to them, is The Band. They have got a real touch of–I don’t know what to call it–they’re American music. Even though most of them are Canadian, these guys, except for Helm, the guy from [Arkansas]. But in a funny way, there is an element of jazz there, or something I can recognize as a kinship to jazz. But early rock’n’roll-when it still had something–is basically just blues, anyway.

You hear that particularly in The Band, in the early Band numbers. They’re almost straight blues, even when they’re reinventing them, and Robertson and Helm are writing pieces for them. They are still the straight blues pattern. What happens after that just becomes noise.

R: Do you know Robertson, or Helm?

B: I used to go to things, I used to, I didn’t get to know either of them well. I liked–what’s-his-name? The guy who died? Danko?

R: The bass player. Rick Danko.

B: Yeah. But he also played, he played other instruments occasionally. He sang. He was an interesting guy. And one guy hanged himself.

R: Richard Manuel. The pianist.

B: And that very good guy on the keyboards.

R: Garth Hudson.

B: Yeah. He’s sort of gone now. He wanders around Woodstock, I am told…Robertson is still out there somewhere and Helm is still out there somewhere.

R: Robertson’s in Los Angeles.

B: Yeah, yeah. He got all the money and he and Helm won’t talk to each other. Helm has accused him of plagiarism.

R: Helm lost his voice, that wonderful voice…

B: Ah, terrific voice. That voice that sings that great number, “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down.” Terrific voice. There’s that wonderful film [The Last Waltz] that was made by…

R: Scorcese.

B: Yeah, in which that number in particular…

R: Isn’t it magnificent?

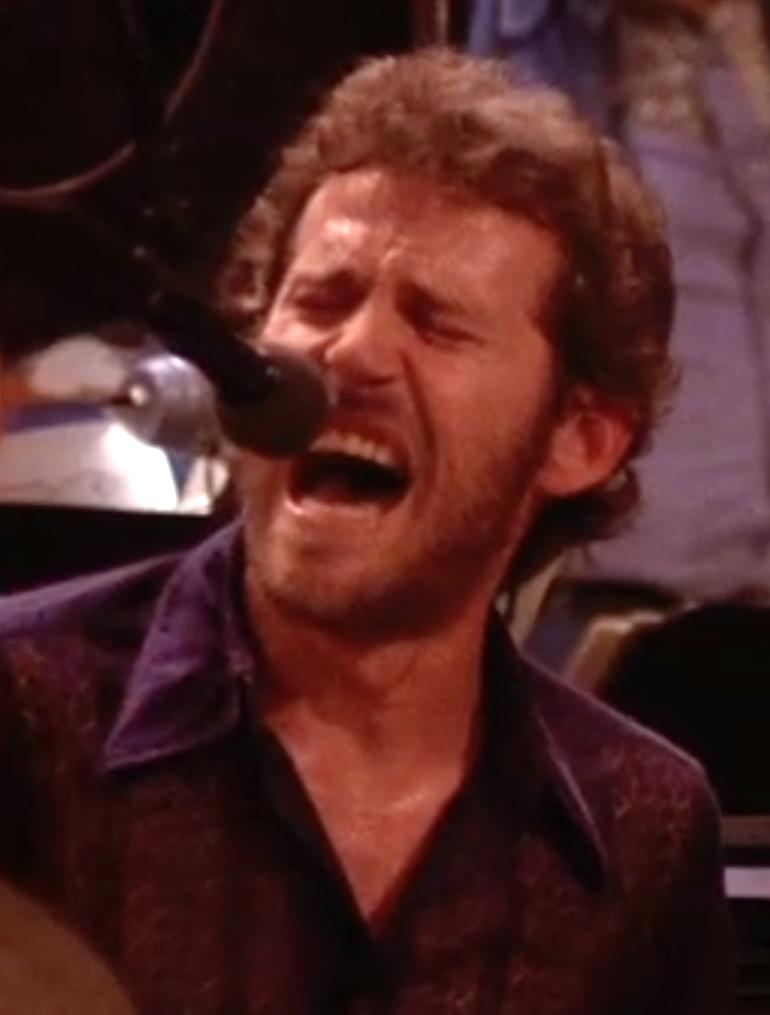

B: It is magnificent; I mean the look on Helm’s face, and the way he is playing the drums as he sings.

R: Well, he’s singing of his forebears there, you know. Such passion and conviction and–

B: Oh yeah, really magnificent.

Jon Pareles’ obituary of Helm in the New York Times fails to mention the RCO All-Stars, a group that Levon formed with Dr. John and Paul Butterfield after the demise of The Band. Here they are on New Year’s Eve 1977 performing “Sing, Sing, Sing,”(not to be confused with the Swing Era classic by Louis Prima).

One especially lasting memory I have of Levon is from an interview that Chet Williamson conducted with him in Worcester many years ago. Williamson began the interview on just the right note by asking Helm about blues legend Peck Curtis, the drummer who played with Sonny Boy Williamson on King Biscuit Time around Helena, Arkansas in the ‘40’s and ‘50’s. Levon recalled the specifics of Peck’s kit and warmed to his youthful memory of seeing Curtis and Sonny Boy on the rear end of a flat-bed pick-up as it wound its way around the towns of the Mississippi Delta. You may recall the scene in “The Last Waltz” in which The Band recounts their hang with Sonny Boy shortly before his death in 1965. Here’s the silent footage of Williamson and Robert Jr. Lockwood that I wrote about on this blog entry a few months ago. The second sequence of footage shows a band with Curtis on drums.

Bob Margolin, the Brookline native who played guitar with Muddy Waters for several years in the 70’s, appeared with him in The Last Waltz. Muddy’s performance of “Manish Boy” featured Paul Butterfield playing a tension-filled warble on harmonica that Waters praised for “holding my voice up,” and the appearance by the great bluesman was lauded for giving this celebration of rock a touch of gravitas. Margolin published a detailed account of the experience in Blues Revue magazine in 2002, and concluded with a story about Levon: “Recently, I read Levon Helm’s inside story of The Last Waltz in his autobiography, This Wheel’s On Fire. I was shocked to find that because of time and budget constraints and Band politics, Muddy was nearly bumped from the show. Levon fought bitterly behind the scenes and prevailed to not only keep Muddy in but to indulge him with me and [pianist] Pinetop [Perkins] too. We were treated as honored guests at The Last Waltz and I enjoyed the once-in-a-lifetime jam afterwards, but Levon never told us about making a stand for us. He just made us welcome. Ultimately, this gracious, classy, and tough gentleman was responsible for [our] good time there.”

Here’s Levon and Garth Hudson in 1983 with a short but sweet rendition of Sonny Boy’s “Don’t Start Me to Talkin’.”