A Chicago Bluesman in Roxbury With Worcester’s Babe Pino and Brookline’s Bob Margolin

During a visit to Boston last weekend, I drove to Dudley Square in Roxbury to catch a glimpse of the Highland Tap, a nightclub I frequented in the early seventies. Saturday’s jaunt felt a lot less daring than the risk of venturing to ghetto bars forty-four years ago, but short of moving to Chicago, I was game for hearing blues wherever I could find it, especially in the kinds of places where seeing how it was received was nearly as satisfying as hearing it played.

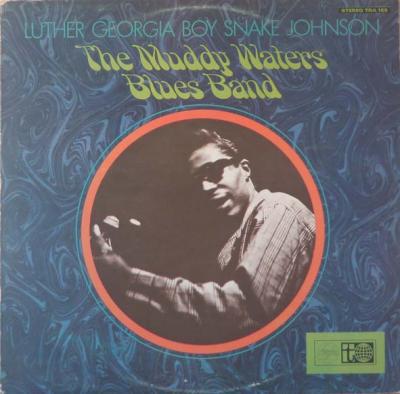

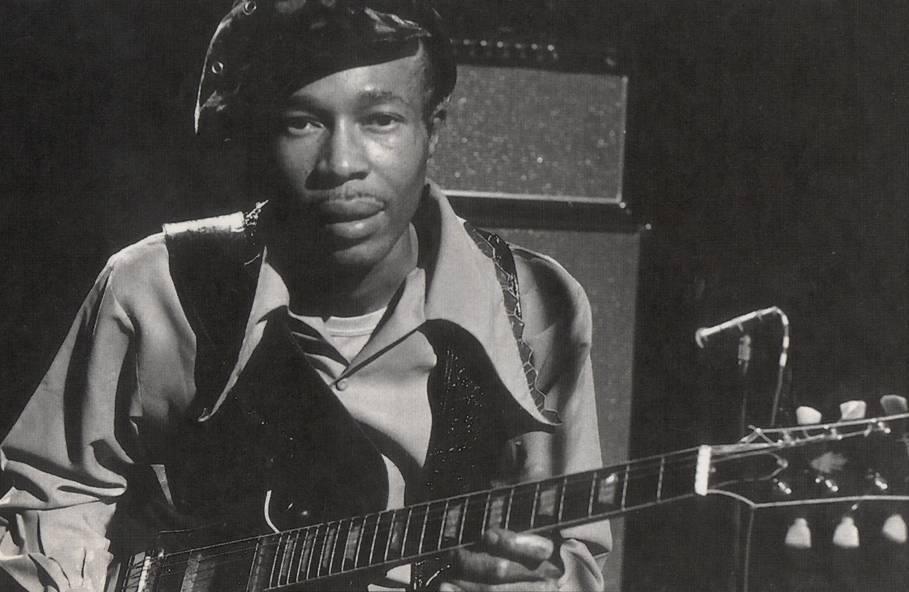

Back then, darkened by night and the elevated train tracks on Washington Street, the Highland Tap was home base for Luther Johnson. Luther, whose nicknames included “Georgia Boy” and “Snake,” was a Chicago bluesman who’d toured with Elmore James and Muddy Waters before settling in Boston around 1970. He played biting, no-frills guitar and sang what Muddy proudly called “deep blues.” His local bands attracted some of the area’s finest young players including guitarist Bob Margolin, pianist David Maxwell, drummer Tuffy Kimble, and Babe Pino, the Worcester-born singer and blues harpist who was a personal friend of mine. (Kimble has since spent a couple of decades drumming with the blues world’s other Luther Johnson, “Guitar Junior,” who also got his start with Muddy Waters before he too settled in Boston in 1980.)

I spent the summer of 1971 as a 17-year-old working on a painting crew for the Cambridge Redevelopment Authority. Most of the crew chiefs were African-American, and when my love of blues became apparent one of them told me that a former Muddy Waters sideman was playing locally. I don’t think they knew Luther by name, just that the real deal was nearby in Roxbury. When I asked James Montgomery, the young blues harp player whom I’d met shortly after arriving in Cambridge, he told me it was Johnson and painted such a colorful picture of the Highland Tap that I was impatient to get there that night. Greater Boston was a receptive region for blues by the late sixties and several area venues booked the music, but aside from seeking out soul music and vintage blues at Skippy White’s Records on Washington Street, there was little call to go to Roxbury for live blues.

Luther changed all of that for awhile. The Davisboro, Georgia, native sang the blues six nights a week at the Highland Tap, and he attracted a down-home crowd who let him know he spoke their language. I’ll never forget how enthusiastic a core group of female admirers were for Luther’s brand of blues. Johnson was subtly emotive, his raspy-voice hinting at his background as a gospel singer with the Milwaukee Supreme Angels. His take on the Muddy Waters classic “Long Distance Call” was a surefire audience favorite. Not averse to theatrics, he would slip out the narrow club’s side door by the bandstand and re-enter through the front as he enacted the drama of a man returning home to discover that “another mule is kicking in my stall.”

In the clip below, Johnson’s behind a pair of shades backing Muddy Waters with Otis Spann, Pee Wee Madison, Paul Oscher, and S.P. Leary. This was filmed at the Copenhagen Jazz Festival in 1968.

Luther also played occasional gigs at local colleges and festivals, but before he got much traction outside the ‘hood he became ill with brain cancer. He persevered through harrowing medical treatments and made gigs in Boston and upstate New York, but death claimed him in 1976 at age 41. Luther’s recorded legacy is small, but his records, a mix of slow blues, shuffles, and boogaloo, are worth seeking out. His signature tune was the devastating slow blues “Lonesome in My Bedroom.” I heard him sing it virtually every night, and here’s the version he recorded for the 1972 album, They Call Me the Snake.

The first bluesman to really capture my attention was Albert King. A neighborhood kid who’d joined a record club mistakenly ordered Albert’s 1967 Stax LP, Born Under a Bad Sign. He didn’t go for it, but knowing of my passion for soul music, he thought I might, and he was right. King’s mix of funky backbeats, crisp horns, and crosscutting guitar lines proved irresistible to me as a budding blues lover.

B.B. King was next. The King of the Blues has given me more thrills than just about anyone else in music, and his 1964 concert recording, Live at the Regal, made it clear that there was nothing to compare with hearing the blues among enthusiasts who engage in the call and response rituals that factor at every level of the music.

It would take a little longer for me to warm to the deep, spare sounds of Chicago Blues, but that eventually happened when I heard Muddy Waters singing “I Just Want to Make Love to You” as I was exiting the basement clubhouse of a high school girlfriend. The combination of Muddy’s declamatory singing, Little Walter’s reverb-laden harmonica, and Fred Below’s big drop after-beat froze me in my tracks. That was in 1969, about 15 years after Chess Records first released Muddy’s classic, but it sounded better than anything on local radio. I caught the bug for Chicago Blues in that moment, and nothing’s been the same since.

Worcester had Chicago Blues surrogates of its own in Babe Pino and his guitar-playing brother Kenny. I first met Babe in grade school. He was cool even then, a natural born leader of the pack, except there was no one else at that age hip enough to join the pack. In his early teens, Babe fronted The Arcades and Born People, fledgling groups that played bare bones rock’n’roll in the style of the Stones, Animals, and Yardbirds. Then, as it happened for legions of young musicians with their ears to the ground in the mid-sixties, he heard the Paul Butterfield Blues Band and suddenly a new musical ideal emerged, one combining blues fundamentals with crack musicianship. Babe developed quickly as a harmonica player while Kenny followed suit as a guitarist emulating Mike Bloomfield, the Kings (B.B., Albert, and Freddy), and jazz masters Kenny Burrell and Pat Martino.

By the late sixties, the Pinos were playing seriously fine blues and r&b with a group they called, in tribute to a Chicago block steeped in blues lore, the Maxwell Street Blues Band. They honed their sound at a Worcester dive called Poli’s Cafe, and soon earned recognition from the masters, appearing as the opening act on bills with Muddy Waters, James Cotton, Mississippi Fred McDowell, Buddy Guy & Junior Wells, and Bonnie Raitt. (Bonnie lived for awhile in Worcester in the late sixties and played the city’s coffeehouses before coming to national prominence.)

Notwithstanding Maxwell Street’s renown, their prospects on the local front began dimming around the time that I began following Luther. Babe and I were high school seniors in 1971, and one day we cut school and went to see The French Connection. Like everyone else in the house, we were enthralled by the spectacular chase scene that took place on the BMT elevated line in Brooklyn. After the movie, I told Babe the subway line reminded me of the tracks on Washington Street above where Luther played, and minutes later we were barreling down the Mass Pike in his Austin Healey, a cramped two-seater with a missing vent window that, even with sips off a jug, kept us shivering all the way.

Luther was a man of few words, but he made me feel at home by inviting me to his booth at the Highland Tap on my early visits. Then late that summer we discovered that we shared the birthday of August 30. On the evening of the 29th, Muddy Waters played a Sunday twilight concert on Boston Common, and after his set a couple of friends and I beat a path to the Tap in anticipation that he’d be coming by to hang with Luther. That didn’t happen (Muddy had another gig that night in Revere), but when we got to the club, we found Luther in the midst of a birthday party. I made it known that the next day was mine too, and answered that it was my 18th, a careless disclosure that marked me as three years underage. One of the bartenders who’d been serving me all summer made a veiled threat to put me out, then declared that with two birthdays to celebrate, drinks were on the house. All that buzz, needless to say, made returning to high school a few days later seem dreadfully conventional.

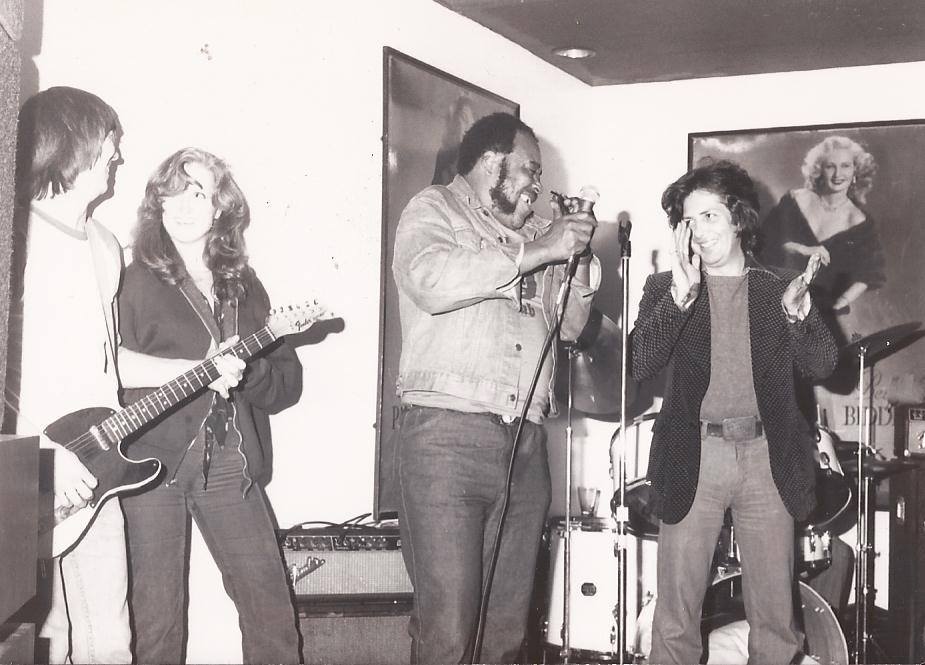

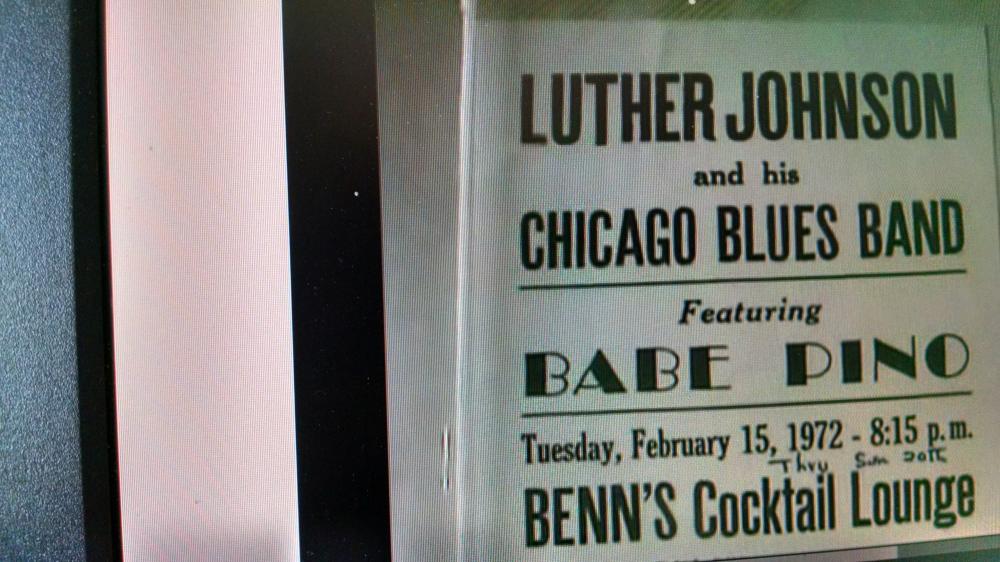

Four months later, I took Babe to see the man who held forth under the Orange Line Elevated. Johnson already had a harp player, but when I told him that Babe had sat in with Muddy and Cotton, he called him up, and before the night was over he asked him to join the band. For the next few months, Babe blew harp and sang an opening number at the Dudley Square club, then moved on with Luther to Benn’s Lounge in Dorchester and the Parker Street Lounge in Mission Hill, both rough and tumble joints that made the carpeted Highland Tap feel uptown by comparison.

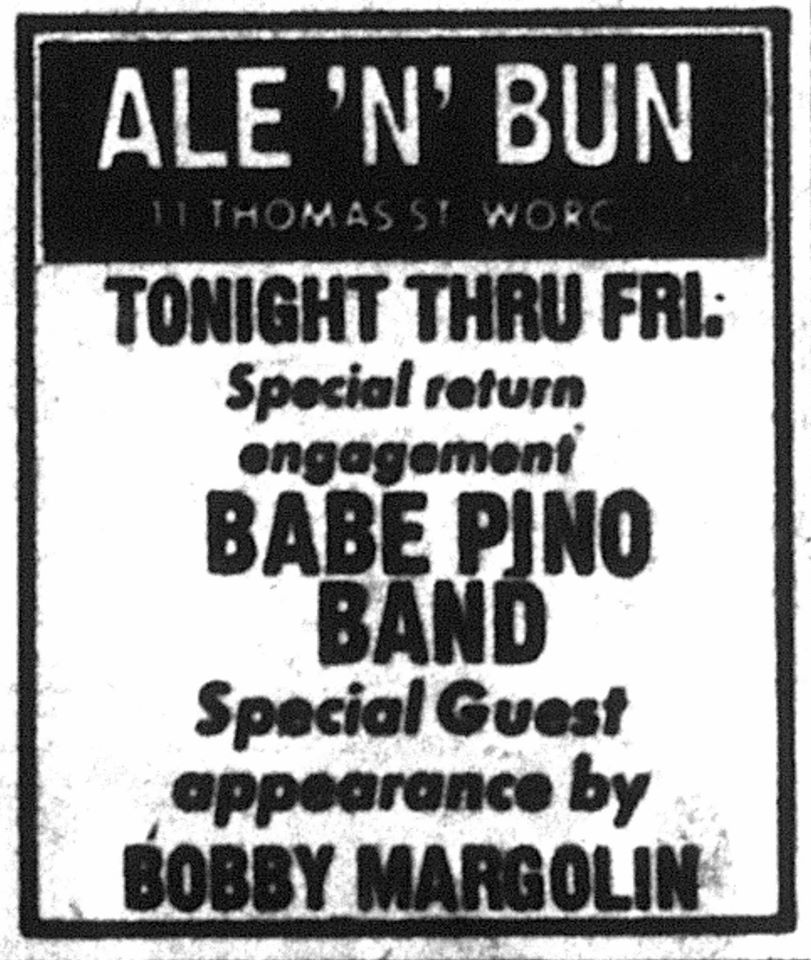

Late that year, Pino and Bob Margolin moved away from sideman work with Luther and formed Babe Pino and the Boston Blues Band. The group was anchored by keyboard player Al Arsenault, bassist Wolf Ginandes, and drummer Dave Agerholm, and it played the blues with passion, authority, and a serious touch of funk. Its home base was the Ale’n’Bun, the former site of Poli’s Cafe, and they fanned out from there to gigs at Caesar’s Monticello in Framingham, Lennie’s-on-the-Pike in Danvers, and Paul’s Mall in Boston. By today’s standards, the Boston Blues Band was an outfit that would be making records by the week, but back in the day it failed to attract a record label worthy of its excellence.

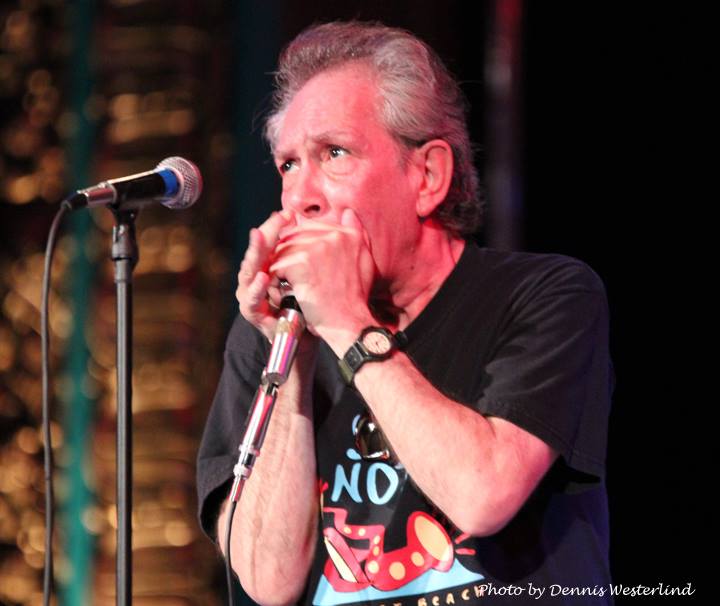

Muddy Waters played Paul’s Mall too, and shortly before a week-long engagement at the Boylston Street club late in 1973, he’d fired veteran guitarist Sam Lawhorn and was looking for a replacement. Bob Margolin was in the house on opening night, and having impressed Muddy on several occasions when he heard him playing with Luther and Babe, he was invited to the great bluesman’s hotel room the next day for an audition. Muddy was instrumental in establishing the modern prototype for blues bands in Chicago with a group that featured his slide guitar or Little Walter’s harmonica as its principal solo voice backed by rhythm guitar, piano, bass, and drums. By the early seventies, his band had expanded to include a third guitarist, but in an era given to ear-splitting electric guitar overload, Muddy’s remained a much subtler force dedicated to grooves and to an ensemble that could hang with his behind-the-beat phrasing. Muddy called it “delay” singing.

Margolin was first moved to pick up a guitar by Chuck Berry, but once he heard Muddy’s music, he thought of it as “the most powerful music I ever heard in my life.” Recalling his successful audition, the Brookline native told Muddy’s biographer Sandra Tooze, “He was kinda tickled to see somebody who was young that wanted to do it, because, for the most part, more modern players wanted to play more modern things.” When Muddy offered him the job, Margolin “was very aware of what that would mean, that it was a very big opportunity, and if I didn’t do it, it would be like putting a cap on my career.”

Bob spent the next half dozen years on the road with Muddy, whose band solidified in the seventies around Pinetop Perkins, piano, Jerry Portnoy, harmonica, Margolin and Luther “Guitar Junior” Johnson, guitars, Calvin Jones, bass, and Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, drums. Margolin has written extensively of his experience with Muddy, including the article, What Was Muddy Waters Like? He’ll remain forever linked with the blues icon through their appearance together in The Last Waltz. Margolin was surely the least known musician on stage that night, but Muddy trusted him alone to play the signature riff on “Mannish Boy.” Along with Paul Butterfield’s fierce harp playing and Robby Robertson’s guitar licks, the performance stands as the spiritual center of the The Band’s farewell concert.

Back in Worcester, Babe and Kenny Pino regrouped as The Babe Pino Band and carried on in ever soulful fashion. Kenny would later spend a decade with the great bluesman Johnny Copeland, and now 40 years later, Babe remains the standard bearer of blues in Central New England.

Luther Johnson, who was born Lucious Brinson on August 30, 1934, died on March 18, 1976. He’s buried not far from Dudley Square in the Mount Hope Cemetery in Mattapan. On the great footage below, he sings his original, “Woman Don’t Lie,” and Fenton Robinson’s modern blues standard, “Somebody Loan Me a Dime.” That’s Sonny Thompson, who toured for many years with Freddie King, at the piano.