At Work on Christmas Eve

Miles Davis had a genius for making the most of limitations, whether they involved his own as a trumpeter, or others whose playing compelled him, even if in a negative way. He also had a feeling for posterity, and seems always to have recognized the iconic value of both his image and his raspy voice. Years before Columbia Records began to exploit the fetish that fans make of every note and utterance by the trumpeter, Prestige captured Miles telling Rudy Van Gelder, “Hey Rudy, put this on the record, all of it.” Miles made the point on Christmas Eve 1954 after Thelonious Monk interrupted Milt Jackson’s introduction on “The Man I Love” to ask testily, “When am I supposed to come in, man?” (Hear the complete exchange and Take 1 here: Miles Davis “The Man I Love”)

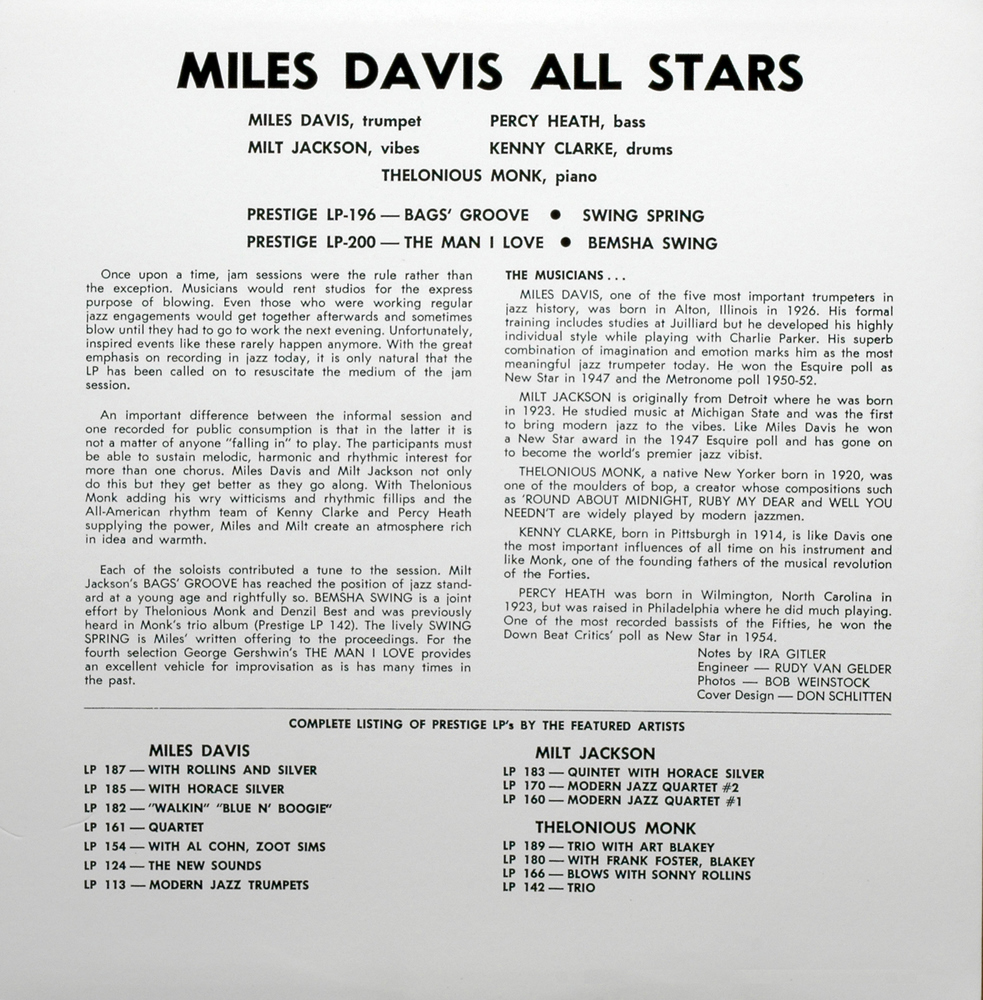

Miles, Monk, Jackson, Percy Heath, and Kenny Clarke (the latter three were members of the Modern Jazz Quartet) recorded the Gershwin ballad and three originals (“Bags’ Groove,” “Swing Spring,” and “Bemsha Swing”) on a session originally released as the Miles Davis All Stars, and subsequently reissued as Miles Davis and the Modern Jazz Giants. It’s one of the most storied in jazz history, and Miles devoted over a page to it in Miles: The Autobiography, where he said that he wanted “to clear up once and for all what happened between me and Monk.”

The session is the one where Miles reputedly told Monk to “not play behind me, except on ‘Bemsha Swing,’ a tune written by Monk. The reason I told Monk to lay out is because Monk never did know how to play behind a horn player.” Miles said the pianist didn’t play “too tough,” that he didn’t “push the rhythm section…I just told him to lay out when I was playing, because I wasn’t comfortable with the way he voiced his changes…I wanted to hear the rhythm section stroll without a piano sound.”

Miles says there “wasn’t any argument…So I don’t know how that story got started about me and Monk arguing so bad we almost came to blows.” Later he adds, “If I had ever said something about punching Monk out in front of his face…then somebody should have just come and got me and taken me to the madhouse, because Monk could have just picked my little ass up and thrown me through a wall.” Monk confirmed this view two years after the session when he told Ira Gitler, “Miles’d got killed if he hit me.”

Monk’s biographer Robin Kelley offers a less benign view than Miles, saying that the pianist was “indignant” about being asked to lay out. He acknowledges that Monk “allegedly did various things to sabotage the session.” Kelley says that Monk was annoyed with the date on several counts, not least that it was a sideman gig on Christmas Eve paying only scale; that Monk was “a little envious” of Milt Jackson’s new success with the Modern Jazz Quartet; and that none of his music was proposed for the date, but Ira Gitler persuaded producer Bob Weinstock to include one by Monk. Thelonious slyly chose “Bemsha Swing,” the tune he’d co-written with Denzil Best that Weinstock had rejected two years earlier on a Monk trio session for Prestige.

Kelley reports that in 1963, Monk reflected on the session with a pair of French journalists. “The conditions were terrible. We were tired. The producer was not in the best of moods. It was Christmas Eve, and everyone wanted to go home.” He added that Miles came back to his Manhattan home with him, and “I even had a hard time getting rid of him that night.” So much for artistic differences getting in the way of friendship.

While some of the studio specifics between Miles and Monk remain matters of conjecture, there’s been a consensus for six decades that tension between the players only added to the session’s success and critical acclaim. Miles credited it with pushing him further in the direction of utilizing space to “breathe through the music.” He called the record a classic, and said it’s where “I started to understand how to create space by leaving the piano out and just letting everybody stroll. I would extend and use that concept more later.”