Nat Hentoff, a restless, uncompromising paragon of modern, independent journalism, died on January 7, 2017, in New York at the age of 91. His family was by his side, and Billie Holiday, whom he presented on the 1957 television special, “The Sound of Jazz,” was on the turntable. Hentoff was fond of quoting the late New York Times columnist Tom Wicker’s observation about their mutual hero I.F. Stone. “He said he never lost his ‘sense of rage.’ Neither have I.” While Nat aimed his journalistic lance primarily at issues related to what the Times obituary identified as “free speech, wayward politics…and the Constitution,” jazz played a major role in shaping his core values. In a 1997 interview with C-Span, he told Book Notes host Brian Lamb that his youth in Boston was marked by two disparate phenomena, violent anti-Semitism and something “more fulfilling. I was introduced to jazz, and that’s become a basic concern and passion of mine ever since.”

Hentoff began his 1986 memoir Boston Boy with the story of a group of rabbis conducting a ritual excommunication of him at a motel in Tewksbury, Massachusetts, because of a petition he’d signed protesting Israel’s 1982 invasion of Lebanon. If he’d been called to the motel to defend himself, Hentoff said he “would have told them about my life as a heretic, a tradition I keep precisely because I am a Jew, and a tradition I was strengthened in because I came to know certain jazz musicians at so early an age that they, not unwittingly, were my chief rabbis for many years…I would be excommunicated nonetheless, for what could Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus mean to that court of assizes?” What he meant by “so early an age,” he wrote in a later memoir, Speaking Freely, was eleven, when jazz became his “vocation, the equivalent of a religion.”

While Hentoff ultimately wore many hats as a journalist, it was through jazz that I first encountered him, and I wasn’t alone. Before I was out of high school, many of my friendships were based in a mutual love for the music, and an understanding that our identity with something as unconventional as jazz was a signifier of our youthful thrust for individuality. Nat was of our parents’ generation, but his odyssey as a non-conformist made him one of our most trusted guides, just as he was for many others. A few years ago, as I was preparing an introductory talk for the area screening of a documentary about Hentoff, The Pleasures of Being Out of Step, I asked the African American spouse of one of my in-laws if Hentoff’s name rang a bell “Sure,” she said, “I learned about jazz through all those liner notes he wrote.”

I grew up in Worcester, but my parents gave us a substantial Boston orientation in our young lives that made Hentoff, among numerous other figures, a writer of ready interest to me. I learned from his politics and his progressive attitudes and insights on race matters. I was also impressed by his admiration for one of my favorite writers, George Frazier, the Boston-born jazz critic, style arbiter, and Nixon scold, of whom he wrote, “He came into a room like the first notes of a Lester Young solo– a proclamation of being, a style that could be mistaken for no one else’s.” What I valued most was his gift for conveying something of the profound humanity that lay behind the mythical aura of musicians. Hentoff wrote with a keen sense of how important the jazz life was to its creators, and a knowing appreciation of its significance for those of us for whom the players are priests and priestesses.

He wrote extensively on Duke Ellington and Charles Mingus– he became a confidant of both– and on Lester Young, and while my appreciation for Prez began a long time ago, I’m continually grateful to Hentoff for helping me appreciate how the sweetly poetic sound of Lester’s tenor saxophone playing makes me feel him on a more personal and intimate level than any other jazz artist. In Boston Boy, he wrote, “I had the presumptuous notion that I wanted to do something for [Lester Young], make him feel less alone. I have never seen anyone who was more alone wherever he was. Alone and slightly puzzled…[But] with swinging wit and tenderness, Prez, loose in space, transformed his life every night into what it ought to be.” Has the drive to create ever been more succinctly and eloquently stated?

Through his essays and books, his editorship of the Jazz Review (which is now available on-line in its original layout), and his participation in the groundbreaking School of Jazz in Lenox, Massachusetts, Hentoff helped establish the intellectual framework that guides the present-day profusion of jazz histories and biographies and critical studies. His career began well before jazz studies became ubiquitous on college campuses, and his early writings are replete with invective over the second-class status the music was accorded in concert halls and the groves of academe. His tireless advocacy made a difference, and to no one’s surprise, when the National Endowment for the Arts established the A.B. Spellman Award for Jazz Advocacy in 2003, Hentoff was its first recipient.

Nat’s prominence as a journalist began at age 28 as the editor of Downbeat, a gig that occasioned his move from Boston to New York in 1953, and from which he was dismissed three years later for insisting that the magazine diversify its staff. In 1958, he began writing a weekly column for the Village Voice that focused mostly on free speech, freedom of the press, and education issues as played out in newsrooms, classrooms, the courts, and the public square. He was also the author or editor of several canonical works of jazz history and criticism, including The Jazz Makers; Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya’; and The Jazz Life. But he wasn’t solely about jazz. He knew from the blues and country music, and wrote substantial pieces on Merle Haggard and Bob Wills. He was also one of the earliest critics to take Joan Baez and Bob Dylan seriously, writing the liner notes for the 1963 album, The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan, interviewing Dylan for Playboy, and profiling him for The New Yorker. Under William Shawn’s storied tenure at The New Yorker, he also profiled Gerry Mulligan, Justice William Brennan, and Cardinal John O’Connor. Nat’s outspokenness as a pro-life opponent of abortion led the oft-proclaimed atheist to find common cause with the New York archbishop, an association that puzzled and alienated many of his colleagues on the Left. But for Hentoff, principles came first.

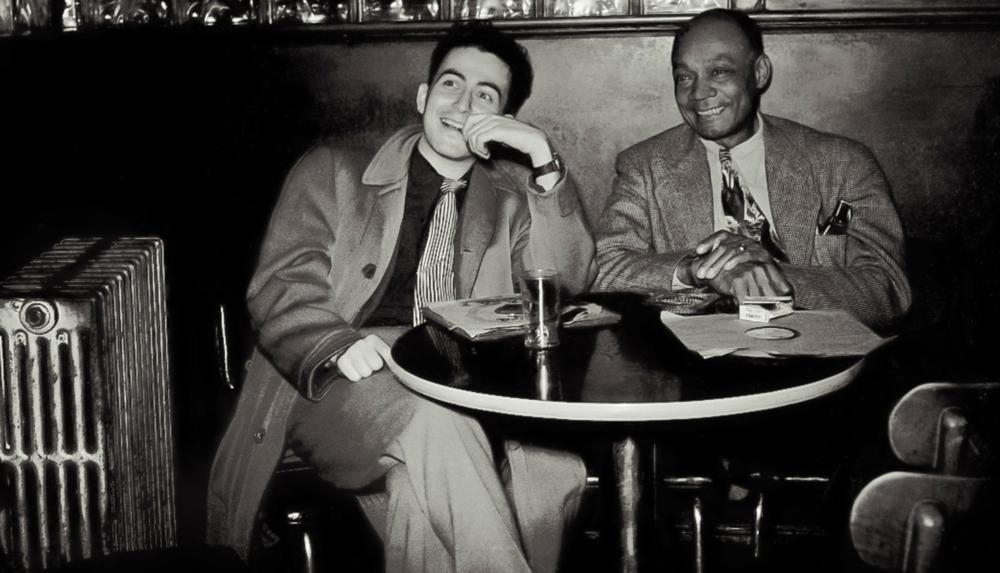

In his later years, Nat wrote for the Wall Street Journal, and for a couple of decades he had a back page column in Jazz Times, where he wrote on emerging musicians, old masters (i.e., friends), and topical matters like the absence of women in the ranks of the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra. It’s there where he plugged a Wynton Marsalis feature of mine in 1998. The compliment came as a complete surprise to me as I read the column, and it induced both a thrill and a humbling sense of challenge. I’d yet to meet Nat by then, but we soon connected over the phone (his number appeared at the bottom of his columns) and had a couple of meetings in New York. He was an excellent source for an article I wrote for the Boston Globe Magazine in 1999 on “Duke Ellington’s New England.” Duke gave only four complete performances of his celebrated extended work, “Black, Brown, and Beige,” in 1943. The night after its Carnegie Hall premiere, the 18-year-old Hentoff attended the performance at Boston’s Symphony Hall. 21 years later, when the 65-year-old Ellington was denied a special Pulitzer Prize for lifetime achievement, it was Hentoff to whom he famously said, “Fate is being kind to me. Fate doesn’t want me to be too famous too young.” But he was less pithy and more revealing when he confided to him his belief that what it really meant was that jazz was still being “treated like a man you don’t want your daughter coming home with.”

Nat’s musings often began with an exchange he’d had with Duke, Miles Davis, Billie Holiday, Pee Wee Russell or Dizzy Gillespie. In the best sense of the word, he was a name-dropper, but only in the service of an idea or insight, never to make someone who wasn’t there feel deficient or left out. Indeed, he wasn’t above revealing his occasional exchanges with musicians that made him reconsider a conceit or scratch his head over a witty rejoinder. Where Whitney Balliett, his colleague on The Sound of Jazz, had a rare gift for conveying the sound of music in prose, Nat was given to describing its effect on him. Of the cantorial-like cry he heard in Ornette Coleman’s saxophone playing, he said, “It jolted me back to when I was a boy, sitting next to my father, in a shul in Boston’s Jewish ghetto.” In Lester Young’s tenor saxophone playing he felt a “pulsating ease.” Blues pianist Otis Spann impressed him with “the sound of a deep river of feeling, sometimes rushing against rocks and sometimes deceptively serene.”

Nat titled one of his anthologies, Listen to the Stories, and he got great ones because he was an empathetic listener. In the Hentoff documentary, Phil Woods made it plain: “When musicians saw Nat enter the room, they didn’t think, ‘Ah, here comes a critic.’ They said, ‘Here comes a friend of the music’.”

As the Times and other obits made clear, the Boston Latin and Northeastern alum was even better known as a friend of the First Amendment. “The Constitution and jazz are my reasons for being,” he declared over the sounds of Duke Ellington’s “What Am I Here For?” in David Lewis’s documentary. “The First Amendment is a way of life.” He said it was the individual expressiveness of jazz players that fostered his reverence for democracy and everyone’s right to speak. His Village Voice column was devoted to that principle for fifty years, and that’s what drew Lewis to his subject. The filmmaker, a former producer at 60 Minutes, knew nothing of Hentoff’s jazz writing. He told the Times, “I went to high school in Westchester in the 1970s, reading Hentoff at the time. His voice always stood out in what was such an awful period in public life—Watergate, post-Vietnam, the Church Commission, FBI abuses, malaise—and he was writing about all of it, so I always knew who he was.”

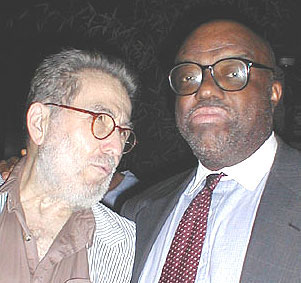

Among the sources that Lewis interviewed for the film were the writers Stanley Crouch and Amiri Baraka, First Amendment lawyer Floyd Abrams, Justice Brennan, and Nat’s wife Margot Hentoff, who was a frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books. There’s a vintage clip of him squaring off against William F. Buckley, Jr. on a Firing Line episode devoted to civil rights and Black Power. Dan Morgenstern is seen poring through the record library of the Institute of Jazz Studies, where he chooses a quote from Hentoff’s liner note essay for Miles Davis’s Sketches of Spain, “Miles plays with an authenticity that is neither strained nor condescending.” Crouch lauds his work as a producer at Candid Records. “Some of those records are as good as any record made at any time,” he says, and adds that while critics often feel they’d make the best producers, “Nat Hentoff proved that he could.”

Candid was a subsidiary of Cadence Records. The label was doing well with Julius LaRosa, Andy Williams, and the Everly Brothers when its founder, pianist Archie Bleyer, hired Hentoff to launch a jazz label. (In 1962, after Candid had folded, Cadence released a Kennedy family parody called The White House by Vaughn Meader. It was the biggest and fastest selling record in history at the time.) Hentoff wrote about the Candid venture in his memoir, Speaking Freely. “The fantasy was common to jazz buffs, as we used to be called. Someday, somehow, I would have my own record label and record my favorite musicians. The releases would be pure jazz, and therefore would last for generations. Untold numbers of people all around the world would remember my name gratefully.”

Nat was speaking tongue-in-cheek, of course, but by 1997, when Speaking Freely was published, Candid had more than stood the test of time. Though it was in operation for less than two years, Hentoff captured some of the most vital music of the era, ranging from politically-charged works by Max Roach, Abbey Lincoln, and Charles Mingus; to career milestones by Clark Terry, Booker Ervin, Steve Lacy, Cecil Taylor, and Booker Little; to classic blues by Memphis Slim, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Otis Spann. Candid also documented landmark albums by two Massachusetts natives: Phil Woods’s extended work, Rites of Swing; and the 38-year-old pianist Jaki Byard’s first-ever release, Blues for Smoke.

Hentoff performed a veritable public service by recording Spann, for the pianist, one of the greatest in blues history, had recorded only two singles by 1960, seven years into his long tenure with Muddy Waters. Nat had heard Spann with Muddy at the 1960 Newport Jazz Festival, and he made up for lost time by recording over twenty titles by the pianist and his collaborators Robert Jr. Lockwood and St. Louis Jimmy Oden. Lockwood is heard playing guitar with Spann here on the Big Maceo blues classic, “Worried Life Blues.”

In a music populated by partisans of one style or another, Hentoff’s tastes were refreshingly catholic, and in this regard he was a model for listeners who found themselves drawn to jazz that ranged from what Beaver Harris termed, “ragtime to no time.” Nat’s opposition to cant, including the notion that jazz must be “innovative” to be of value, was especially inspiring to me as a young fan who was drawn equally to traditional, swing, bebop, and post-hard bop, from Bechet to Basie to Bird to Coltrane. In his Boston youth, where he spun jazz records at WMEX and made the rounds of the Savoy, Storyville, and Hi-Hat, he grew as fond of old school clarinetists Edmond Hall and Pee Wee Russell as he did the modernists. At Candid, he struck a balance between traditionalists and iconoclasts, and recruited Russell and Coleman Hawkins to make their first session together since the historic Mound City Blue Blowers date of 1929. Jazz Reunion included this poignant blues that Pee Wee named for his wife Mary.

The best-known of the Candid releases are also the most political. We Insist: Max Roach’s Freedom Now Suite; Abbey Lincoln’s Straight Ahead; and Charles Mingus Presents Charles Mingus. Fifty-five years later, Roach’s magnum opus is still the most fully realized work of a political nature in jazz history. Combining the drummer’s music and Oscar Brown’s Jr.’s lyrics in support of the civil rights movement in the U.S. and the nascent anti-apartheid movement in South Africa (where the record was banned), Freedom Now’s sense of urgency is made all the more insistent by the boldness of Lincoln’s singing and the whap! of Max’s drumming. We Insist and Lincoln’s Straight Ahead announced Abbey’s transformation from supper club chanteuse to what Hentoff described as “the Abbey Lincoln she had long wanted to be,” a soul-bearing voice of liberation.

Mingus Presents Mingus includes “Original Faubus Fables,” Mingus’s riotous lampoon of Arkansas Governor Orville Faubus, the segregationist who blocked the integration of Little Rock’s Central High School in 1957. Faubus’s resistance prompted President Eisenhower to send in federal troops, though not before Louis Armstrong, in the most controversial statement of his career, called him out for inaction. Mingus had first recorded “Fables…” for Columbia in 1959, but only as an instrumental since the label objected to including his lyric decrying “Nazi fascist supremacists,” and the chant of “Two four six eight/They brainwash and teach you hate.” Columbia, as it were, stood in the schoolhouse door, but there was no such resistance coming from Hentoff at Candid.

Nat’s last anthology of writings, At the Jazz Band Ball: Sixty Years on the Jazz Scene, was published in 2010. In his epilogue, “My Life Lessons,” he says, “The Candid recording that means the most to me was made in 1961 by twenty-three-year-old Booker Little…I knew he’d be a shaper of the future of jazz because of his vision…and his sound reminded me once again of what Duke Ellington had told me: ‘A musician’s sound is his soul’.” Alas, Booker died of uremia only six months after he’d recorded Out Front. Nat says he was “startled” when the trumpeter dedicated his composition, “Man of Words,” to him. “It was his description– in sounds, dynamics, and rhythms– of the writing process.” True to form, Hentoff then jumps from his memory of Booker to a concluding paragraph in which the Dixieland cornetist Jimmy McPartland relates a story about Bix Beiderbecke. For Nat Hentoff, every lick of this music was fresh, valid, interconnected, and loaded with truth, love, and surprise.