Phenomena at Newport: the White Blues Hero and the Folk Rock Anti-Hero

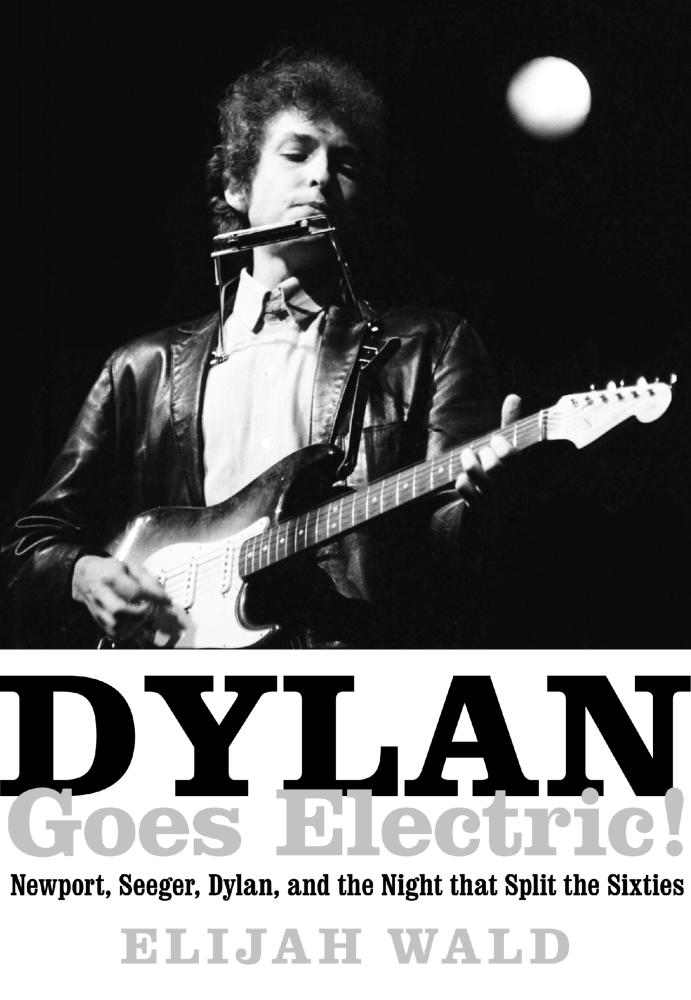

July 25th marked the 50th anniversary of Bob Dylan going electric at the Newport Folk Festival. The milestone is being widely commemorated, and it follows the sale two years ago of the Fender Stratocaster he played that Sunday night. Elijah Wald’s new book, Dylan Goes Electric: Newport, Seeger, Dylan, and the Night That Split the Sixties, tells the story more accurately and contextually than any previous renderings. Published by Dey Street, a William Morrow imprint, it’s a great read that’s getting plenty of attention, including a glowing review in The New York Times, where Janet Maslin expressed “surprise” that there’s more to the myth of Dylan’s sonic assault on Newport than what’s “been contemplated ad nauseam” for a half century. (Click here for the review.)

My interest in that epochal weekend has long been focused on the leading role the Paul Butterfield Blues Band played in bringing electricity and Chicago blues to Newport. It was also the first racially integrated ensemble to play the festival since it was established in 1959. To be sure, two other festival performers also plugged in that weekend: the great bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins, and the Chambers Brothers, which like many gospel-style groups of the era, used electric guitars but no drums. Butterfield led a pedal-to-the-metal amplified outfit, and that was part of its legend. The band’s debut LP, released in October 1965 on the previously acoustic-only Elektra Records, underscored this feature in a back cover banner unique in music history: “We suggest you play this record at the highest possible volume in order to fully appreciate the sound of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band.”

I wrote a feature on the festival when news broke of Dylan’s guitar being sold at Christie’s on December 6, 2013 for $965,000. (Click here to read Dylan’s Guitar: Credit Mike Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield.) Wald’s emphasis is different and more comprehensive than mine, but as a blues historian and performer, he addresses the phenomenon of white boys playing the blues foursquare, and he provides a fresh new account of Butterfield’s Friday afternoon set that began with Alan Lomax’s infamous introduction of the band.

Lomax was among the few folklorists to have embraced rock’n’roll as a valid folk form, and he hailed the Chambers Brothers as exemplars of “our modern American folk music…rock’n’roll.” But he was less impressed by the prospect of a 22-year-old white blues harpist fronting the first Chicago blues band ever to appear at Newport. Lomax knew from blues: twenty four years earlier, while on a Library of Congress field recordings sojourn, he’d discovered Muddy Waters (then known by his birth name, McKinley Morganfield) in Clarksdale, Mississippi. The discovery occurred a year or more before Butterfield and guitarist Michael Bloomfield were even born, and their youth only added to Lomax’s doubts about their ability to deliver the real thing. Unbeknownst to Lomax, Muddy had encouraged Butterfield from the outset of his bemused encounter with the white teenager when he began hanging out at the South Side blues clubs where Waters held forth in the late ’50s. (Muddy had been at Newport twice before: he played the Newport Jazz Festival in 1960, and for his 1964 performance at the folk festival, he played solo acoustic guitar in tribute to Son House.)

(In this clip from Murray Lerner’s documentary, Festival, Butterfield plays Little Walter’s “Juke” at the July 23 blues workshop. Joan Baez, Geoff Muldaur, and Mimi Baez appear delighted.)

Lomax’s intro was snide and presumptuous. He complained to the audience about having to wait for the band to set up, and Wald’s account has him saying that Butterfield had come “highly recommended, already the King of Chicago, which is a big, uh, tribute…I’m anxious to find out whether it’s true or not.” Albert Grossman, who’d become Dylan’s manager in 1962 and remained so until 1970, was a Chicagoan who’d urged that Butterfield be booked by the festival, and he didn’t take kindly to Lomax’s condescension, which Bloomfield called “rank.” When the two confronted each other off-stage, blows were exchanged and the culture war that “split” the decade had begun.

It’s my contention that all the buzz about Butterfield’s performance and the fight between Grossman and Lomax combined to make Dylan rethink his Newport plans. Wald doesn’t go quite that far, but he allows that “many insiders suggest their fight left [Dylan] itching to stick it to the folk establishment.” He adds that “Dylan was inspired by the presence of the Butterfield band,” which he’d already seen in person at the Village Gate a month earlier, and he’d known Bloomfield for a couple of years. While they’d yet to release more than one side (“Born in Chicago” on an Elektra sampler), the band already had a reputation among those in the know. That weekend, Dylan told a Time magazine reporter, “For me right now, there are three groups: Butterfield, the Byrds, and the Sir Douglas Quintet.”

Dylan had already “gone electric” in January of ’65 when he jumped down the manhole of “Subterranean Homesick Blues” and scored his first chart success. “Like a Rolling Stone,” recorded a month before Newport with Bloomfield playing the song’s signature leads and turn-arounds, was all over the radio by the festival weekend. In his book-length study, Like a Rolling Stone: Bob Dylan at the Crossroads, Greil Marcus hears in Bloomfield’s playing something “triumphant, like a hawk in the sky…when, out of instinct, out of desire, out of a smile somewhere in his memory, Bloomfield finds the sound of a great whoosh, and for an instant a rising wind blows right through the rest of the music.”

Wald recounts that Dylan arrived at Newport on Saturday and asked Bloomfield to hastily assemble an ad hoc outfit that would back him on his main-stage set the following night. The group, which rehearsed all night Saturday at a Newport mansion leased by George Wein, coalesced around Butterfield’s rhythm section, bassist Jerome Arnold and drummer Sam Lay, players who’d honed their chops with Little Walter and Howlin’ Wolf. Barry Goldberg, a sidekick from Chicago, played the B3 on “Like a Rolling Stone” at Newport, while Al Kooper, who was the organist on the record, played bass in place of Arnold, who fumbled the changes. Kooper had come to Newport on his own as a paying customer, but shortly after his arrival was handed backstage passes and deputized for the band. Six weeks earlier, he’d arrived at the Highway 61 Revisited session assuming he’d play guitar, but as he’s humbly related ever since, “Just hearing Bloomfield warm up ended my career as a guitarist…Until then, I’d never heard a white man play guitar like that.”

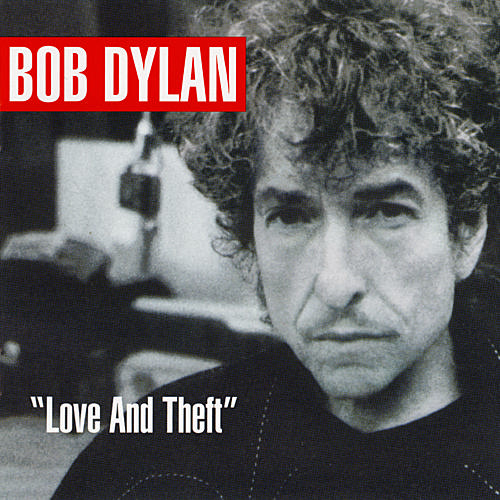

Of course, only Bob Dylan can say definitively how much his decision to “go electric” was inspired by the events swirling around Butterfield that weekend. But as far as I’m concerned, if Butterfield wasn’t there, Dylan’s electric premiere wouldn’t have happened until a later date. What is certain is that Newport ’65 certified two significant developments in popular culture. Dylanesque “folk rock,” and Butterfield as the new archetype of the white bluesman. The latter is a complex phenomenon lying deep in the American grain, ranging from 19th century blackface minstrelsy to The Jazz Singer; from Paul Whiteman as the King of Jazz to Benny Goodman as the King of Swing to Elvis Presley as, simply, the King. As a troubadour who’s continually channeled blues mythology and elements of its floating verses, Dylan may be the ultimate exemplar of the phenomenon. He acknowledged as much with his 2001 album, Love and Theft, which most likely borrowed its name from Eric Lott’s 1993 study, Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class.

Dylan’s penchant for disguising his sources brings to mind T.S. Eliot’s adage, “talent imitates; genius steals.” Butterfield was more an imitator than a thief, and at Newport he put his stamp on classics by Elmore James, Junior Parker, and at least three by Little Walter. He also sang the newly minted signature tune of his rough and tumble hometown, “Born in Chicago.” The song’s composer, Nick Gravenites, was part of the entourage that traveled to Newport with Butterfield, and he sang a couple of tunes with the harpist at one of the festival’s blues workshops. Wald quotes Barry Goldberg acknowledging, “We always carried that sort of Chicago toughness,” an attitude embodied in Gravenites’ song about friends lost to gunfire on the streets.

Butterfield’s musicianship earned him the respect of the masters, especially Muddy Waters and B.B. King, as well as lesser-known figures on the South Side. His first steady gig was as a sideman with guitarist Smokey Smothers in a group that included Arnold and Lay. When success came their way, he and Bloomfield continually acknowledged the originators and helped raise the quality of the venues they played and the money they earned. As Sam Lay has said, “Butterfield opened doors for [black musicians], and I know because I followed him through those doors.” Billy Boy Arnold said much the same when he spoke at the induction of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band at the Rock’n’Roll Hall of Fame this spring. Arnold, whose fifties originals “I Wish You Would” and “I Ain’t Got You” were famously covered by the Yardbirds, noted that it wasn’t until Butterfield brought his integrated band into Chicago’s North Side clubs that black bluesmen like himself began headlining there too.

Dylan instructed Bloomfield not to play “any of that B.B. King shit” when he recruited him for the Highway 61 Revisited sessions. The directive has often been misconstrued as a slam against blues, but even a quick perusal of Dylan’s memoir or a set list from his Theme Time Radio Hour show reveals his love for the music and icons like Muddy, Little Walter, and Sonny Boy Williamson. But the blues form would have limited his scope and imagination as a songwriter, and he just didn’t have the chops as a guitarist or harmonica player to do much more than shadow the masters. That hasn’t stopped him from employing a succession of guitar players, including Denny Freeman, Jimmie Vaughan, Doyle Bramhall II, Charlie Sexton, and Duke Robillard, who are disciples of the late King of the Blues, but he’s challenged them to play beyond their comfort zones.

Bloomfield was the first of them, and Dylan’s never stopped hailing him. As recently as a 2009 interview with Rolling Stone, he said, “The guy that I always miss and I think would still be around if he stayed with me, actually, was Mike Bloomfield. He could just flat out play. He had so much soul. And he knew all the styles, and he could play them so incredibly well. He was an expert player and a real prodigy. He started playing early. He could play like Willie Brown and Charlie Patton. He could play like Robert Johnson way back then in the early 60’s…He could play the pure style of country blues authentically.”

But while Bloomfield dispensed with blues licks on Highway 61, it was the bluesy bite of his Telecaster and Butterfield’s authoritative singing and Little Walter-inspired harp that raised such a clatter fifty years ago at Newport. Wald quotes festival performer Geoff Muldaur from John Milward’s 2013 book, Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock’n’Roll (and Rock Saved the Blues). “The most important thing to happen at Newport in 1965…was that an integrated band came in from Chicago to play real Chicago blues…and this white guy was so good, and had a band that could pull it off and hold their own among the kings…In the blink of an eye, there would be two hundred thousand blues bands in the world based on that model.”

Those countless bands, however, have only rarely mirrored the integrated nature of the Paul Butterfield Blues Band. Butterfield’s own groups remained a mix of blacks and whites, and so too the bands led by his Chicago compatriot Charlie Musselwhite. But under the Butterfield archetype, blues, which was in decline in popularity among blacks, underwent a sweeping makeover, and over the past fifty years it’s become a music with a predominantly white face. That’s a complicated story for another time and space at this blog, but it’s a major legacy of Newport ’65.