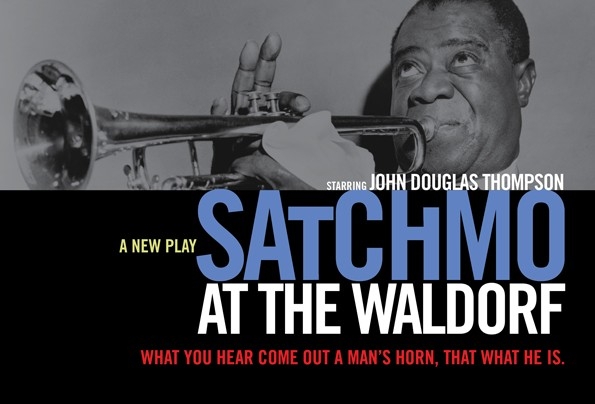

I was in Lenox yesterday to interview the actor John Douglas Thompson and playwright Terry Teachout about “Satchmo at the Waldorf,” and to see the one-man, one-act play at Shakespeare & Company. The play and performance are extraordinary, a tour de force of writing and acting in which Thompson portrays Louis Armstrong and Joe Glaser and Miles Davis, all with aplomb and exquisite humanity.

As Teachout told me, “The play is really about love and betrayal,” meaning there’s a deeply personal story between Armstrong and Glaser, his longtime manager, at the heart of this drama. But Davis’s presence underscores a second layer of betrayal, one driven by a new black consciousness which emerged in the 40’s and disdained the entertainer’s role that Armstrong epitomized. And notwithstanding the praise that Miles extended to him later in life (“You can’t play anything on a horn that Louis hasn’t played”), bebop appeared to posture itself as a manifesto-like rejection of Armstrong’s musical values. Behind this personal and generational conflict, of course, is the larger matter of race; “Satchmo at the Waldorf” offers a poignant exposition of two distinctly different courses that blacks negotiated through the complex maze of racism in the 20th Century.

Thompson admitted to his own “shameful” feeling of “disdain” for Armstrong in our conversation. “I did not think of him as a figure that I should pay attention to…He turned me off and made me feel uncomfortable. I came up jazz-wise with Coltrane and Miles and Herbie Hancock and John McLaughlin. I knew of Armstrong through ‘Hello Dolly,’ but I just wouldn’t even allow his contributions to inform me as to what jazz was…He just didn’t seem to be a factor…But hey, how wrong I was…Through my research, I listened to his recordings from the ’20’s, ’30’s and ’40’s, and I watched films of him at the Louis Armstrong House in Queens, and I began to get a picture of his virtuosity, his inventiveness, his iconic stature…I grew to have a whole new respect for this man, and I almost felt shameful in having felt that way about him prior, you know, so here’s the key: knowledge is power! So I got this knowledge on Armstrong and it just changed my whole outlook and made me fall in love with the man, so I’m really happy to be doing this play because it’s like a culmination of my own journey with this artist.”

Among the play’s highlights are scenes in which Armstrong revisits “West End Blues,” the landmark recording he’d made in 1928. The initial scene focuses on the opening trumpet cadenza’s operatic-like grandeur; a later one on its tender, wordless vocal, a sublime counterpart to Armstrong’s horn, and an opportunity for Thompson, who does not play trumpet, to sweetly echo Satchmo’s singing. (Thompson wisely refrains from outright imitation of Armstrong’s speaking voice, but he nails Miles, and his Joe Glaser reminded me of the great Edward G. Robinson.)

45 years ago, Gunther Schuller wrote in Early Jazz, “The clarion call of ‘West End Blues’ served notice that jazz had the potential capacity to compete with the highest order of previously known musical expression.” In hearing how Armstrong’s opening four-note phrase contained “in capsule form all the essential characteristics of jazz inflection,” Schuller hailed it as a model for “the general stylistic direction of jazz for several decades to come.” It remains as compelling a masterpiece as jazz has produced, and Teachout and director Gordon Edelstein have chosen well in utilizing this Hot Five classic for both its musical and dramatic richness.

My interviews with Thompson and Teachout will be posted here next week. Before then, I urge you to make plans to see “Satchmo at the Waldorf” before it closes on September 16 in Lenox, or during its run at the Long Wharf Theater in New Haven between October 3 and November 4. “West End Blues,” and everything else you cherish about Pops, will take on new meaning afterwards.