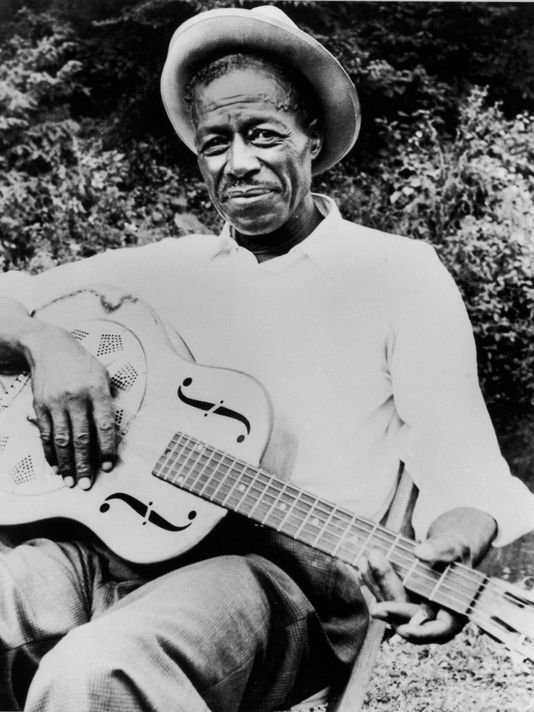

Mississippi Delta Blues Legend in Rochester

I remember the exact moment during my junior year in high school when I first heard Muddy Waters, but I’ve forgotten just when I got my first taste of Muddy’s main man, Son House. Muddy’s great band with Little Walter and Jimmy Rogers floored me right away. It would take a little longer for me to warm to the haunting, solitary sounds of Delta blues, but listening back through Muddy’s catalogue, hearing the Robert Johnson album, King of the Delta Blues Singers, and seeing Mississippi Fred McDowell in person at Worcester Polytechnic Institute drew me in.

Muddy was a 14-year-old when he first caught sight of Eddie James “Son” House, Jr., and he never forgot it. In 1969, he told Downbeat that it made him “light up like a Christmas tree” to see House “running down them strings with a bottleneck. I stone got crazy.” For Jim Rooney’s Bossmen, he recalled House as spellbinding and a rambler. “My copy was Son House. He didn’t never be still like me, cause he’d do a lot of travelin’ all over the Delta. Any time I could get a chance to hear him play, I’d go. Once, he played a month in a row every Saturday night. I was there every night, close to him. You couldn’t get me out of that corner, listening to him. I watched that man’s fingers and look like to me he was so good he was unlimited.”

House was born in 1902 into a world that made sharp distinctions between good and evil. Early on he was warned of the deviltry embodied in a guitar (telling Julius Lester, in 1964, “All before then, I just hated to see a guy with a guitar. I was so churchy!”), and through his mid-twenties he applied his righteous voice to preaching and singing spirituals. But blues and trouble, alcohol and runnin’ around eventually claimed him, and by 1928, inspired by local legends Reuben Lacey and Charley Patton, he was developing his own mastery of the slashing, bottleneck guitar style of the Delta. In 1930, House, Patton, guitarist Willie Brown, and pianist Louise Johnson traveled to Grafton, Wisconsin to make a handful of recordings that are among the most renowned of Delta blues.

When Son was interviewed by Julius Lester in June 1965, he recalled the heady experience of the Paramount sessions. “I got paid forty dollars for making those records. At that time, I just had the big eyes. Forty dollars. Making it that easy and that quick. It’d take me near about a whole year to make forty dollars in the cotton patch. I was perfectly satisfied. I showed off a whole lot with that when I got back to Lula, Mississippi.”

The records (“My Black Mama, Parts 1 & 2,” “Preachin’ the Blues, Parts 1 & 2,” “Clarksdale Moan,” “Mississippi County Farm Blues,” “Dry Spell Blues, Parts 1 & 2,” and “Walkin’ Blues”) made only minimal impact at the time. The late Sam Charters, whose 1959 book The Country Blues helped fuel the blues revival of the the following decade, wrote that Patton and House “sang some of the most moving blues on the Paramount lists, but [they] were too intensely personal to appeal to any kind of large audience.”

The blues revival coalesced around the annual Newport Folk Festivals, where rediscovered legends like House, Skip James, Mississippi John Hurt, and Bukka White played to a critical mass of young whites and music industry movers and shakers. The 1965 festival brought together country bluesmen including Son House and the newly minted Paul Butterfield Blues Band from Chicago. In this revealing montage, House and Butterfield’s guitarist Michael Bloomfield offer unique perspectives on the blues.

House remained largely a local figure in the 1930s, and it was left to those he influenced most, Robert Johnson, Muddy Waters, and Howlin’ Wolf, to carry the Delta blues forward. In 1941, when Alan Lomax encountered Muddy (as McKinley Morganfield) on a field recording trip for the Library of Congress, he asked him about his influences. Muddy named House as a player whom he felt was “about equal” with Johnson. Muddy recorded “Country Blues” for Lomax, and said he’d first heard it played by House as “Walkin’ Blues.” The following year, Lomax returned to the Delta and recorded Son.

In 1943, House moved to Rochester, NY with the promise of finding war-related factory work, and over the next couple of decades he worked for the New York Central Railroad as a laborer and Pullman porter, and as a short order cook at Howard Johnson’s. He abandoned music shortly after his arrival in Rochester, and when he was rediscovered in 1964 he hadn’t played guitar for several years.

House’s rediscovery by Dick Waterman, Nick Perls, and Phil Spiro on June 23, 1964 was one of the signal events of the blues revival. While he hadn’t played in years, he returned to form in due time, and over the next decade played colleges, coffeehouses, and folk festivals where he struck audiences with awe, and a bit of existential terror, over his music and the occasional homiletics (“rambling sermons about the Bible…heaven and hell”) he dispensed between tunes.

Waterman, who shepherded his career and worked overtime at keeping him away from a bottle before showtime, called him the “big dog” of the blues and said that when the music was distilled down to its absolute essence, House was “the elixer.” In his 2004 book, Escaping the Delta: Robert Johnson and the Invention of the Blues, Elijah Wald wrote, “Even in the 1960s, House remained a magnificent performer…House played like a man possessed by a fearsome and consuming spirit…It is impossible to take your eyes off him…He was in his sixties by the time he was captured on film [and] his best performances remain the strongest argument for the blues musician as a sort of secular voodoo master.”

Last month, Son House, who died in 1988, was the subject of a festival hosted by the Geva Theater Center in Rochester. The four-day event included concerts, panel discussions, a dramatic reading of a new play by Keith Glover, Revival: The Resurrection of Son House, and the dedication of a Mississippi Blues Trail marker near the site of his former home in the city’s Corn Hill district.

(Report continues here with a feature on Rochester bluesman Joe Beard, who played an important role in House’s return to blues. And click here to read about an encounter between House and his old protege Howlin’ Wolf on the set of Shindig! in 1965.)