Today is Wardell Gray’s 93rd birthday anniversary. The saxophonist was an iconic figure of modern jazz in the 1940’s, but his death in 1955, most likely from a drug overdose, brought to a sudden end what was already a career in precipitous decline. Gray made only a few recordings as a leader, the last in 1950, and after working with Count Basie’s Septet in 1950 and ’51, he lapsed into drug addiction. Till then, Gray had been a respected non-user who tried to dissuade others from getting involved with narcotics. But when Hampton Hawes returned to Los Angeles in 1953 after a two- year stint in the army, he noticed a change in Wardell. In his autobiography, Raise Up Off Me, the pianist recalled, “Soon as I saw him I knew he was strung. It shook me up.”

A few years earlier, Gray, Dexter Gordon, and Teddy Edwards ranked high in Hawes’ estimation as “keepers of the flame, the ones the younger players held in esteem for their ideas and experience and consistency. Wardell was like a big brother to me…He carried books by Sartre with him and talked about Henry Wallace and the NAACP. When white fans in the clubs came up to speak with us, Wardell would do the talking while the rest of us clammed up and looked funny…Aside from Bird, he was the player we looked up to most.”

Gray is the subject of a documentary by Northampton filmmaker Abraham Ravett entitled Forgotten Tenor. It was released in 1994 and as its name implies, the film ruminates over the ephemeral nature of fame, particularly for a black jazz artist, and the mysterious circumstances of Gray’s death. On May 25, 1955, he was found in the desert near Las Vegas with a broken neck and wound to the head, injuries most likely sustained in a fall after he’d died from an overdose, but ones that only fueled speculation that he’d been murdered, maybe by Vegas mobsters. Wardell’s demise was the basis for a Bill Moody mystery, Death of a Tenor Player.

As for fame, Wardell was a brilliant, in-demand saxophonist, influenced by Lester Young and the new direction that jazz was taking in the mid-forties. He worked for a who’s who of bandleaders including Earl Hines, Benny Carter, Billy Eckstine, Benny Goodman, and Count Basie, and with such trailblazing colleagues as Parker and Gordon. He composed “Twisted,” which Annie Ross lyricized and Joni Mitchell covered in the 70’s. He was seen with Basie on Snader Transcriptions made for television. And the ritualistic tenor battles that Gray and Gordon engaged in drew legions of bebop fans to venues around Los Angeles in the late forties and early fifties, and delighted Jack Kerouac’s thrill-seeking protagonist Dean Moriarty in On The Road.

“[Dean Moriarty] bowed before the big phonograph listening to a wild bop record…’The Hunt,’ with Dexter Gordon and Wardell Gray blowing their tops before a screaming audience that gave the record fantastic frenzied volume.”

Born in Oklahoma City and raised in Detroit, Gray came to prominence with Earl Hines, with whom he worked for nearly three years. He settled in Los Angeles in 1946, where he made his first date as a leader with the outstanding Dodo Mamarosa at the piano. The session included a remarkably complex melody that Gray composed on the changes of “How High the Moon,” and dedicated to Lester Young, “One for Prez.” Another Gray original, “Easy Swing,” may have influenced Charlie Parker’s 1948 recording, “Steeplechase.” In the intervening year, Wardell recorded with Parker’s New Stars for the classic “Relaxin’ at Camarillo” session on Dial, and he and Dexter Gordon recorded the two-tenor prototype, “The Chase.” In 1948, he shared the front line with tenor Allen Eager and trumpeter Fats Navarro on the session that Tadd Dameron led for Blue Note.

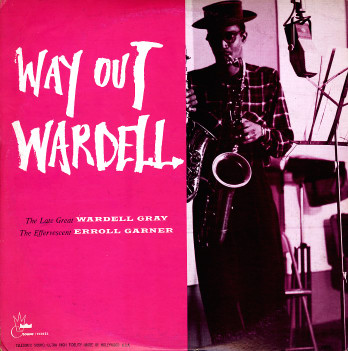

Wardell was recruited by Benny Goodman for the bop-oriented band that BG experimented with in 1948. The King of Swing was, of course, famed as a clarinetist, but he’d played tenor earlier in his career as a session musician, and like Gray, he loved Lester Young’s playing. Gray’s synthesis of Young and Parker, and the melodic beauty of his long-lined phrasing, impressed BG when they shared a bill in Pasadena in April 1947. Wardell appeared with both Howard McGhee and Erroll Garner-led groups on that occasion, and his solo with Garner on “Blue Lou” earned him the French Grand Prix du Disque the following year. Just as he attracted Benny’s attention at the Just Jazz concert in ’47, he continued to earn notice once he joined BG. Downbeat reported that for a performance at the Westchester County Center in 1949, “The star of the evening from an applause standpoint was tenor star Wardell Gray.”

Ravett’s documentary includes a story told by trombonist Eddie Bert about Benny buying a Bundy clarinet for Wardell so that he could play BG’s parts while Goodman indulged himself playing Wardell’s tenor. Benny may have been a frustrated tenorman all along, but from what we know about him, he would have resented Gray being called the “star” of the show.

Two years ago, Gray’s step-daughter Paula Duvall left a comment on this Wardell-related web page. “My mother never spoke of Dad’s death…(I was 11 at the time)…so I was never able to get any authoritative pronouncement as to what happened, or even why…Now that I am old enough to appreciate his artistry, I can appreciate his phenomenal talent. He was a voracious reader of everything from philosophy, Eastern spiritual thought, to mysteries…everything! And, he was an outrageous chef. Rest, well, Dad.”