When I was attending UMass in the ‘70’s, I spent my junior year as an exchange student at the University of Oregon in Eugene. It was not a good match. I’d hardly registered for classes before I felt like a refugee from New England, and by October the feeling had grown so pronounced that I actually rooted for the Yankees when they faced the Dodgers in the World Series. Eugene had its merits, chief among them a lively cinema scene, ready access to spectacular hiking in the Cascades, and KLCC–FM, which played jazz around the clock. But there was a serious lack of live jazz around town. The Eugene Hotel offered good blues, including the Portland-based Robert Cray Band, and shows by West Coast legends Lowell Fulson, George “Harmonica” Smith, and Pee Wee Crayton, but the only jazz concert that fall was by the saxophonist Stan King.

There was, however, a superb record store on 11th Avenue in Eugene that quickly became my home away from home. Prez Records was named for Lester Young and offered a fine selection of vinyl and walls lined with photos and jazz memorabilia. One of these was a picture of Charlie Parker taken at the foot of a stairway at Carnegie Hall in 1947 by the renowned photographer William Gottlieb. At first glance it looks like a shot of Bird in action, but when seen in sequence with other photos from the shoot, it appears to be staged. In either case, it’s a stunning image of Parker, and it so captivated me that the store’s owner, John Fairweather, presented me with a print of it when I told him I’d be returning to UMass at semester’s end. The photo of Bird has been prominently displayed in my homes ever since.

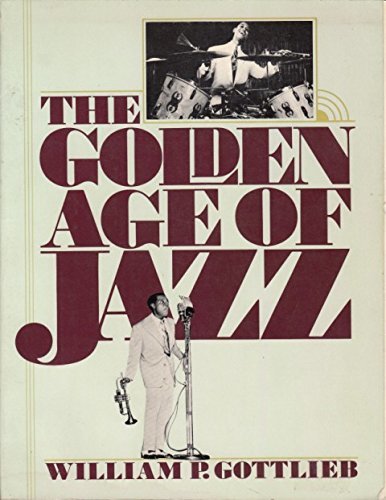

What’s occasioned this memory is the recent posting on Flickr of the archive of Bill Gottlieb photos that the Library of Congress acquired in 1995. Jazz has been well documented by photographers since the ‘20’s (much less so by movie cameras), but these 1600 images may be the most significant of all both for their stunning beauty and for what they depict of the life of musicians on the bandstand and in off-stage settings that range from dressing rooms and street corners to at-home and recreational activities. Milt Hinton’s photos capture something even more revealing of life on the road for black musicians in the era of Jim Crow, but Gottlieb’s lighting technique and sense of composition lend a glorifying aura to his subjects, even in their most quotidian pursuits. Gottlieb published a collection of these photos in 1979 under the title, “The Golden Age of Jazz,” and it’s hard to view this work without indulging in a certain sense of exalted nostalgia for his time and place.

The time is 1938-‘48, and the place is primarily New York, but dozens of the earliest of these pictures were taken around Washington, D.C., when Gottlieb was working as a reporter for the Washington Post. There he picked up a side gig as a jazz columnist, perhaps the first ever for a daily, and when his Post editor informed him the paper couldn’t sustain the budget for a writer and photographer, Gottlieb grabbed a camera. It was also a golden age for photojournalism and the Lehigh University graduate modeled his work on what he saw in the pages of Life. After serving as a photo officer in the Army Air Corps during World War II, he reported on jazz for Downbeat and other periodicals. In 1948, he “quit cold turkey,” and became a producer of educational film strips, eventually becoming the president of a division of McGraw-Hill.

Gottlieb noted that with few exceptions, his photos were taken on location instead of in studios and were intended to supplement his writing. “I consciously tried to take pictures that would augment my text,” he wrote, “that would say something that would go beyond what I could do with just words.” And knowing that most of these pictures would appear in a narrow newspaper column, he “got in close” to his subjects so that what he captured “would still be meaningful to the viewer.” The results are photos of extraordinary intimacy showing complexions and hair weaves, expressions of grief and joy, and in the case of Django Reinhardt, his mutilated left hand. Gottlieb was especially proud of this picture of an anguished Billie Holiday, which he thought achieved his “elusive goal of capturing a subject’s personality or inner qualities.”

Duke Ellington was notoriously cryptic about his composing methods; one of his more revealing admissions was that he couldn’t write music for a man until he saw him play poker, and there’s plenty of evidence among these pictures of back stage card games. Here’s Django Reinhardt among a group of Ellingtonians; the card sharks include Al Sears, Shelton Hemphill, Lawrence Brown and Johnny Hodges.

Mary Lou Williams was a revered supporter of the generation of modernists who emerged in the early ‘40’s, and her New York apartment functioned as a jazz salon. Here she is at the piano with Dizzy Gillespie, Tadd Dameron, and Jack Teagarden looking on. How ’bout those model instruments?

Minton’s was the center of after-hours action in the early ‘40’s. The Harlem nightclub served as a veritable birthplace of bebop where Gillespie, Thelonious Monk, Charlie Christian, Kenny Clarke and others developed the new music. Ralph Ellison immortalized the place in his essay “Golden Age, Time Past,” and Gottlieb captured it both inside and out with his camera. Here’s a famous shot of Monk, Howard McGhee, Roy Eldridge, and the club’s manager Teddy Hill.

Gottlieb photographed Django when the guitarist toured the States with Duke Ellington in 1946. These are among the most widely circulated images of Django and are especially vivid. Note here the pick-like thumbnail on his right hand and the mutilated left hand that Gottlieb was intent on depicting.