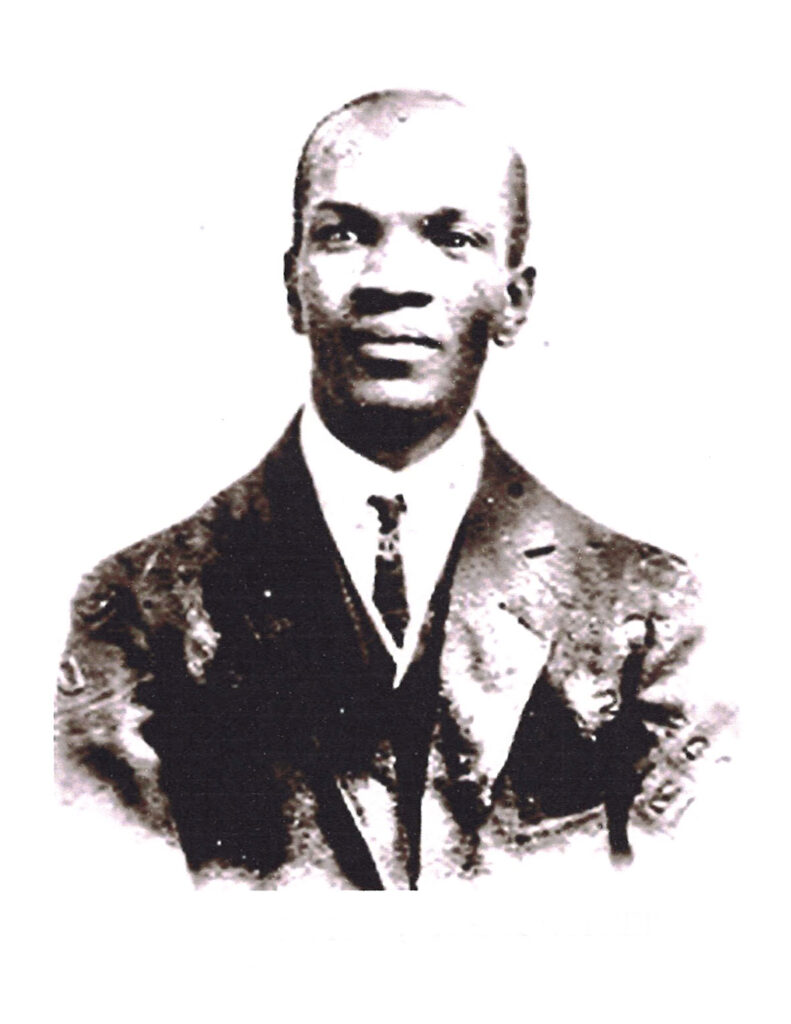

I corresponded with Mark Miller, the Toronto-based jazz historian, over the weekend. Miller wrote on Friday with information challenging the long-held assertion that Ernst Ansermet’s 1919 review singling out Sidney Bechet for praise was the first piece on jazz by an established authority. As Miller discovered, and writes about in a Comment on my Sidney Bechet blog, the honor belongs to Olin Downes, who wrote about a Clef Club orchestra and its trombonist Frank Withers in a review of a show at the Wilbur Theater in Boston in 1918. (Downes was then a music critic for the Boston Post, and later spent over 30 years as the classical music critic of The New York Times..)

Miller’s research does nothing to discredit the substance of Ansermet’s prescient appreciation of Bechet, but it shows that Downes got there first with a remarkably perceptive view of the Clef Club’s performance of “St. Louis Blues,” and Withers’ solo on W.C. Handy’s seminal original. “He plays the trombone as no one else the writer has ever heard…in a manner which makes of this instrument a sort of exclusive personal possession.” There, in a nutshell, Downes apprehends what came to be understood as a major distinguishing feature of jazz, the development of a unique, personalized sound, as opposed to the standardized tone required of symphony and band musicians.

Downes goes on to highlight the voice-like quality of Withers’ sound, and the orchestra’s ability to maintain a high level of inspiration on otherwise “commonplace” material because of its “fire, the sensuous emotion…the emotional abandon, and the endless feeling.” In other words, the same qualities one finds in jazz musicians from King Oliver down to the present.

I’d only encountered Withers once before when I read Frederick Starr’s Red and Hot, a history of jazz in the Soviet Union which I’d first turned to for its account of Bechet’s tour of the USSR in 1926. As it happened, Bechet and Withers had both been with the Southern Syncopated Orchestra in 1919, and were reunited seven years later in the band that drummer Benny Peyton led on a concert tour that brought it to Moscow, Khrakov, Odesssa, and Kiev.

Given the appraisal Downes made of Withers in 1918, it’s reasonable to speculate that he might have become a major figure had he returned to the States and had his playing documented on records. As Miller wrote in an article for Coda, the Canadian jazz magazine, in July/August 2003:

“It was precisely by leaving the U.S. at this early date that Withers effectively limited himself to, at best, an index entry or two in the literature of jazz. In particular, he was now an ocean’s distance from the American recording industry whose preoccupations and priorities would so determine the way in which the music’s history has come to be understood. Withers’ recordings in Paris with Louis Mitchell [‘s Jazz Kings] in 1922 and 1923 were unrevealing, inasmuch as the Kings played in a raggy ensemble style that offered their skills as soloists little, if any, display.

“Withers remained in Europe until 1939… before returning to New York at the start of the Second World War. He was back on the West Coast in time to serve as a pallbearer at Jelly Roll Morton’s funeral in Los Angeles in 1941 and spent his final years in Oakland. The certificate issued at his death in San Francisco in 1952 identified his “Usual Occupation” as porter and his “Kind of Business or Industry” as the Merchant Marine. Of his long and remarkable career as a musician, not a word. “

View the original Coda article, Frank Withers: A Lost Voice and a Lost Article, here.

View the original 1918 newspaper article by Olin Downes here.